In much of the United States we can depend on an extensive system of roads, rails, airports, and other transportation networks to quickly travel to destinations and move goods. In rugged and immense Alaska, however, these networks are much more limited—the state has only approximately 15 major highways. In remote areas Indigenous and rural communities often rely more on rivers and lakes for transportation. During summer, many Alaskans use boats to make their way to nearby villages, hunting grounds, homes, and other important places. In the winter when rivers and lakes freeze over, they switch to snowmobiles, dogsleds, and other means of travel.

In the dark of winter and in the face of climate change, those routes are increasingly becoming more treacherous to use as waterbodies that once reliably froze do so later in the season, thaw earlier in the spring, break up unpredictably, or never freeze at all. Unreliable ice conditions place Alaskans at real risk for hardship, accidents, and drowning—especially in low sunlight months when ice conditions are difficult to visually assess. As a result, ground travel and activities such as subsistence hunting for food have become harder, longer, and increasingly more life-threatening tasks.

Tracking Ice With Citizens and SAR

To understand and predict the coverage of Alaska's changing ice, the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) runs the Fresh Eyes On Ice project. NASA's Citizen Science for Earth Systems Program, a Competitive Program in NASA's Earth Science Data Systems Program, provides funding and other support for Fresh Eyes on Ice. The project uses field studies, remote sensing data, cameras and buoys, historic data, and community-based monitoring and measurements to track past and current river and lake ice conditions. Fresh Eyes On Ice shares what it learns with the National Weather Service as well as with a tribal consortium called the Tanana Chiefs Conference and other local partners to educate and protect communities.

Along with funding, NASA also provides openly available data to the Fresh Eyes on Ice team, such as synthetic aperture radar (SAR) measurements. Alaska’s large size—approximately 600,000 square miles—and dark winters make it virtually impossible to visually survey the state’s ice cover with aircraft or optical satellite sensors. But SAR instruments aboard satellites can create images without the need for reflected light as optical sensors do. Day or night, they can bounce their radar beams off Earth’s surface to acquire detailed information about its features. NASA's archive of SAR data is the Alaska Satellite Facility Distributed Active Archive Center (ASF DAAC), which is located at UAF. For Fresh Eyes on Ice, SAR is an immensely useful technology, and the project has recently begun working with SAR data to measure ice cover.

"We love SAR data because winter here is dark and cloudy, and with the data we can see what's happening no matter what the sky looks like," said Dr. Katie Spellman, a UAF ecologist and a science educator for Fresh Eyes On Ice. "We're figuring out how we can use SAR to give accurate ice cover predictions across different regions of Alaska, which is huge and requires variations in our approach due to changes in terrain and other factors. We're also using citizen scientists to provide ground-based information to validate the SAR measurements we make."

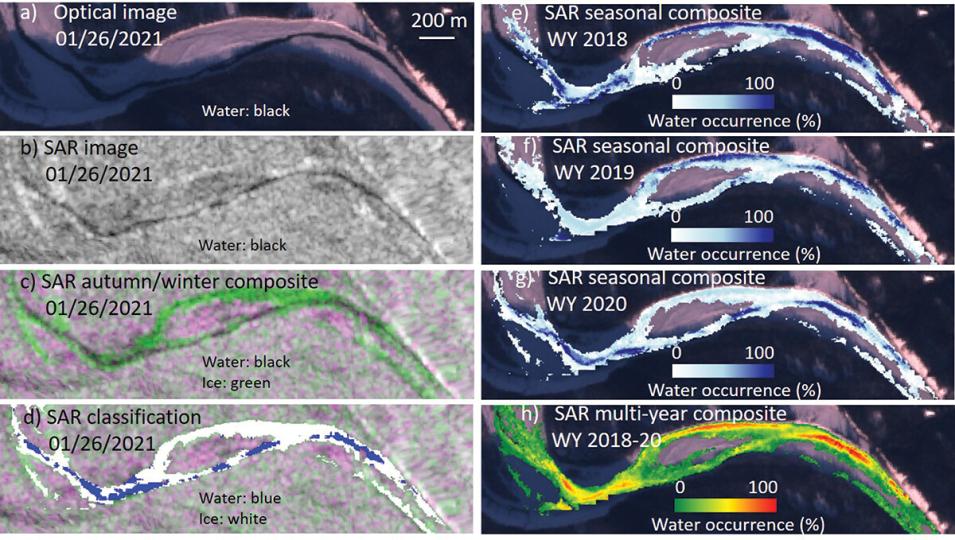

The project recently completed its first two studies using SAR and citizen science data. The first study aimed to create data analysis methods for detecting open water zones in Alaska and was led by UAF researcher and Fresh Eyes on Ice remote sensing specialist Melanie Engram.

“We developed a classification system for detecting open water zones using Sentinel-1 C-band SAR data for rivers in early winter to discriminate between ice cover and open water,” said Engram. “Previous SAR river ice classification approaches have focused on one or two river reaches, often with an emphasis on moving ice during spring break-up. To make our system more broadly useful, we studied 12 reaches from eight rivers for training and validation with the aim to combine data from different river types to create current open water zone maps.”

Ice, snow, and open water reflect SAR signals in different ways and can vary even more depending on location. On top of that, it can be difficult to tell what is what when ice, snow, and open water are mixed together, as is often the case along a river. To train the system to accurately identify each type of surface, Engram compared satellite-acquired SAR data from specific locations indicating ice and open water with ground-based images from the same space and on the same date. The images were captured by on-shore cameras, researchers in the field, and citizen scientists. Citizen science images were taken by community-based monitoring teams or individuals and uploaded to the Fresh Eyes on Ice Observer portal. The images were then used to confirm or refute what the SAR river ice classification system was detecting.

Engram said the system is currently 65% to 93% accurate depending on where it is used, and it can detect open water zones down to 10-meters in width or length.

“The system can also be used to perform historical analysis of an area to determine where open water develops year after year,” said Engram. “And once customized, it can be automated to provide current open water zone maps for Alaskan and other rural northern communities worldwide to aid safer travel on ice.”

The second SAR study characterized how ice cover has changed in Alaska across recent decades. Dr. Dana Brown, a UAF ecologist and geographer supporting Fresh Eyes On Ice, led the second study that examined trends in seasonal ice cover across south-central Alaska’s Copper River Basin from 1973 to 2021. Along with NASA and the National Science Foundation, the National Park Service also funded the study because it wants to ensure people have access to the land it manages on the east side of the river.

"The Park Service contacted me and said that local people are really concerned because they can't get into the park or access traditional lands within it," said Brown. "To anyone living along those rivers, the changes have been obvious and huge. For example, there are areas of the river that remain open year-round now."