The small, round Carolina Chickadee (Poecile carolinensis) is frequently spotted in backyards in the southeastern U.S. When it’s not at the bird feeder, it resides in wooded areas. But as temperatures change, Carolina Chickadees may be less commonly sighted in the southeast.

How Birds Respond to Extreme Weather

Carolina Chickadee (Poecile carolinensis) was observed less frequently after extreme heat. Image credit Jeremy Cohen.

New research finds that several bird species, including the Carolina Chickadee, have shifted their behavior in response to extreme weather. These responses vary based on the duration of the extreme weather and characteristics of the bird species, such as migration patterns.

Birds may be harbingers of a changing climate. They are sensitive to temperature changes and they are a good taxonomic group to study because they are easily observed by researchers and have diverse feeding and migration habits.

Using data from eBird, a global citizen science initiative, and high-resolution weather data, this research investigated how 109 different bird species responded to extreme temperature and drought conditions throughout eastern North America.

“For the first time, we can look at how species responded immediately following extreme weather conditions over the scale of an entire continent,” said Dr. Jeremy Cohen, who led the research as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Bird Observations and Extreme Weather

Bird enthusiasts around the world have contributed over 650 million records to the eBird mobile application managed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, which is now one of the largest databases of bird sightings.

The mobile application asks users to fill out a checklist describing which species are present where the user is birding. eBird asks users to confirm that they are submitting a “complete” checklist of all species observed, allowing researchers to also infer which species were not present. In this way eBird is different from other citizen science applications, in which users only record the presence of notable species. “To understand how extreme weather is impacting birds, knowing when species are not present is just as important as knowing when they are present,” said Cohen.

Cohen’s analysis of eBird data found that immediately following extreme weather, certain birds were observed less frequently than after normal weather conditions. But changes in bird occurrence were dependent on the duration and type of extreme weather and the characteristics of different species.

“Heatwaves are defined as extreme temperature anomalies persisting over a few days or weeks, while droughts typically persist over months or years,” said Cohen. Using Daymet weather data, Cohen and team looked at extreme weather events over weeks, months, and seasons to determine how birds respond over these different time periods. The Daymet data collection at NASA’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory Distributed Active Archive Center (ORNL DAAC) provides daily meteorological data for the entire North American continent spanning a 1 km x 1 km spatial resolution. These data are especially useful in remote areas or in areas with limited instrumentation.

Daily Daymet data are available back to 1980, and Cohen used average weather conditions between 1980 to 2003 as a baseline and calculated weather anomalies from these averages.

Species Variations

Cohen found that immediately following extreme weather, certain birds were observed less frequently than following normal weather conditions. “Birds are not a monolith, though, and we found that different species reacted differently,” said Cohen.

Analyzing eBird data for 109 species allowed Cohen and colleagues to investigate changes in bird presence across bird characteristics such as body mass, foraging behavior, migration distance, and prevalence throughout eastern North America. Out of all of these characteristics, migration distance and prevalence (how common a bird is) were the biggest predictors of behavior shifts in response to extreme weather.

At weekly scales, birds that are year-round residents or migrate only short distances were present less often following a week of extreme heat.

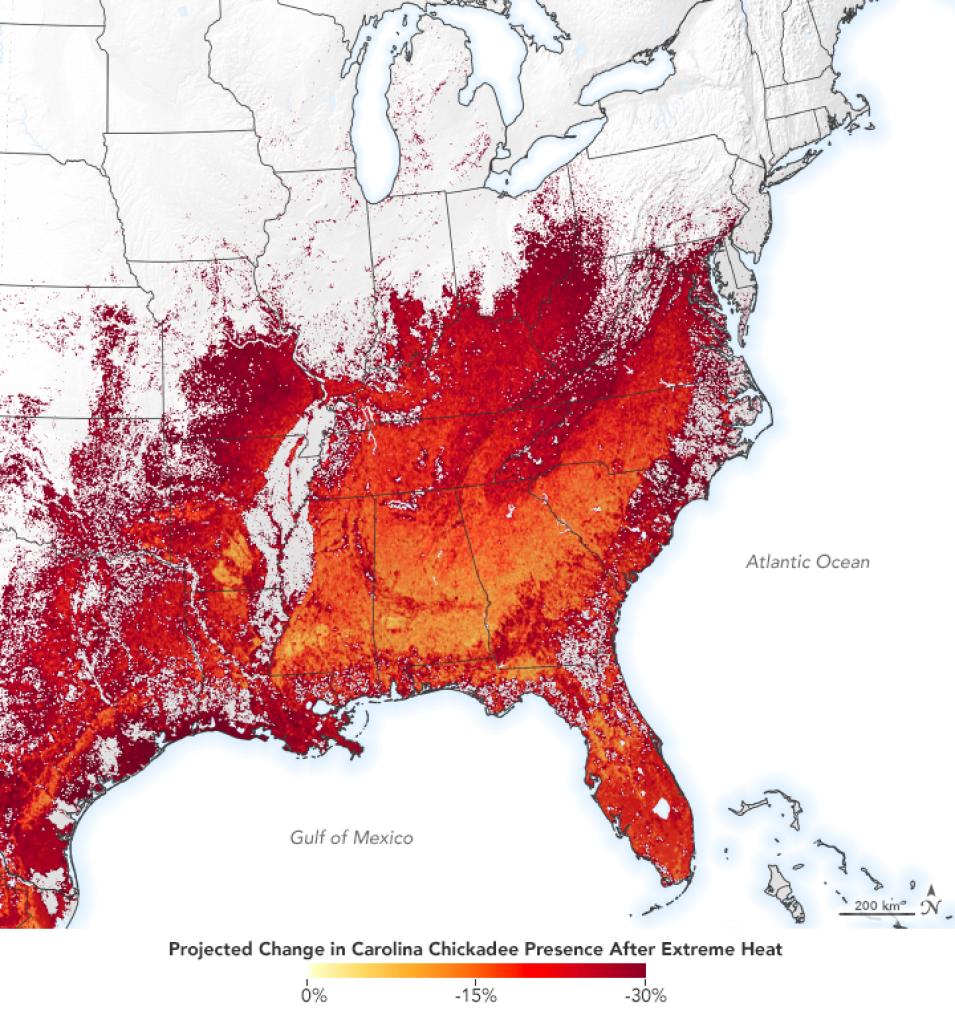

The Carolina Chickadee is an example of such a species. It was observed fewer times after a week of extreme heat, Cohen found. Cohen looked at bird sightings immediately after extreme weather conditions so that the research didn’t conflate the potentially fewer citizen science observations with the impact on bird activity.

The Chickadee was most affected by extreme temperatures at the edges of their range, such as in Texas and southern Louisiana.

After a week of extreme heat, the Carolina Chickadee was less present, compared to normal weather conditions. Image credit NASA's Earth Observatory.

It’s difficult to tell what happens to birds when they are reported less often by eBird users, but we know that birds can't afford to reduce their activity for long periods of time, Cohen said. Many of the species that occur less frequently during extreme weather may shift their distributions north or to cooler locations. But some birds may die off if they don’t find a habitat more amenable to their feeding or breeding habits.

Surprisingly, birds that migrate longer distances were observed more often after a week of extreme heat. Cohen wasn’t sure why this was, but it may be because migrating birds are often exposed to warm, tropical temperature conditions. Also many tropical migrant birds are insect-eaters and could be pursuing insects that are active on a hot day.

In addition to temperature, Cohen looked at how birds responded to extremely dry conditions. Commonly occurring birds such as the American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) weren’t affected by seasonal drought. In general, more common species were found to be less impacted by drought.

The Northern Parula (Setophaga americana), which migrates from southern Florida or Mexico to the northeast in the summer, occurred less frequently after a season of drought, as compared to the common American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos). Image credit Jeremy Cohen.

Less common birds such as the Northern Parula (Setophaga americana), however, were adversely affected. The small warbler migrates north from southern Florida or Mexico in the summer, and was found to be present less frequently after a season of drought. Less common birds are often specialized to a certain habitat or food source, which extreme drought could disrupt.

Enabling Citizen Science

“This research would not have been possible without the high-resolution weather data and the citizen science data,” said Cohen. “Citizen science data has become increasingly valuable in enabling the analysis of species distributions over broad spatial extents.”

NASA's Citizen Science for Earth Systems Program (CSESP) advances the use of citizen contributions to Earth science research by directly supporting citizen science projects and by deploying technology to further citizen involvement in research. One such project supported by this program combines bioacoustic data collected by citizen scientists with satellite and environmental data to monitor bird diversity in Sonoma County, California.

The combination of satellite data and citizen science observations can enable innovative research in biological diversity, especially modeling the distribution of different species. Learn more about species distribution and occurrence data in the new Biological Diversity and Ecosystem Forecasting data pathfinder and toolkit.