Observing seasonal changes

As he attended the lectures, Belote found that he and de Beurs had a common thread in their research interests: that of ecosystem disturbance. Belote wanted to sort out the factors that can push a landscape over the edge. A dry grassland, such as the Colorado Plateau, might remain stable even after disturbances like fire, drought, or heavy animal and human activity. But sometimes, disturbances can change a grassy prairie to scrubby desert. Belote was especially interested in how land use, such as the intense grazing from ranching, affects an area; at what point can it transform an ecosystem long-term?

Similarly, as a phenologist, de Beurs studies how disturbances change a system, by observing the subtle evidence of plant and animal life cycle events. Triggered by seasons and climate, these life cycles are a closely connected chain of events that sustain an ecosystem. Plants bud when temperature and moisture are just right, bearing flowers, fruit, and seeds that support insects and animals; insects hatch and become food for birds. If something is introduced that disturbs these patterns of timing, effects can cascade through the system, and changes show up on a larger scale.

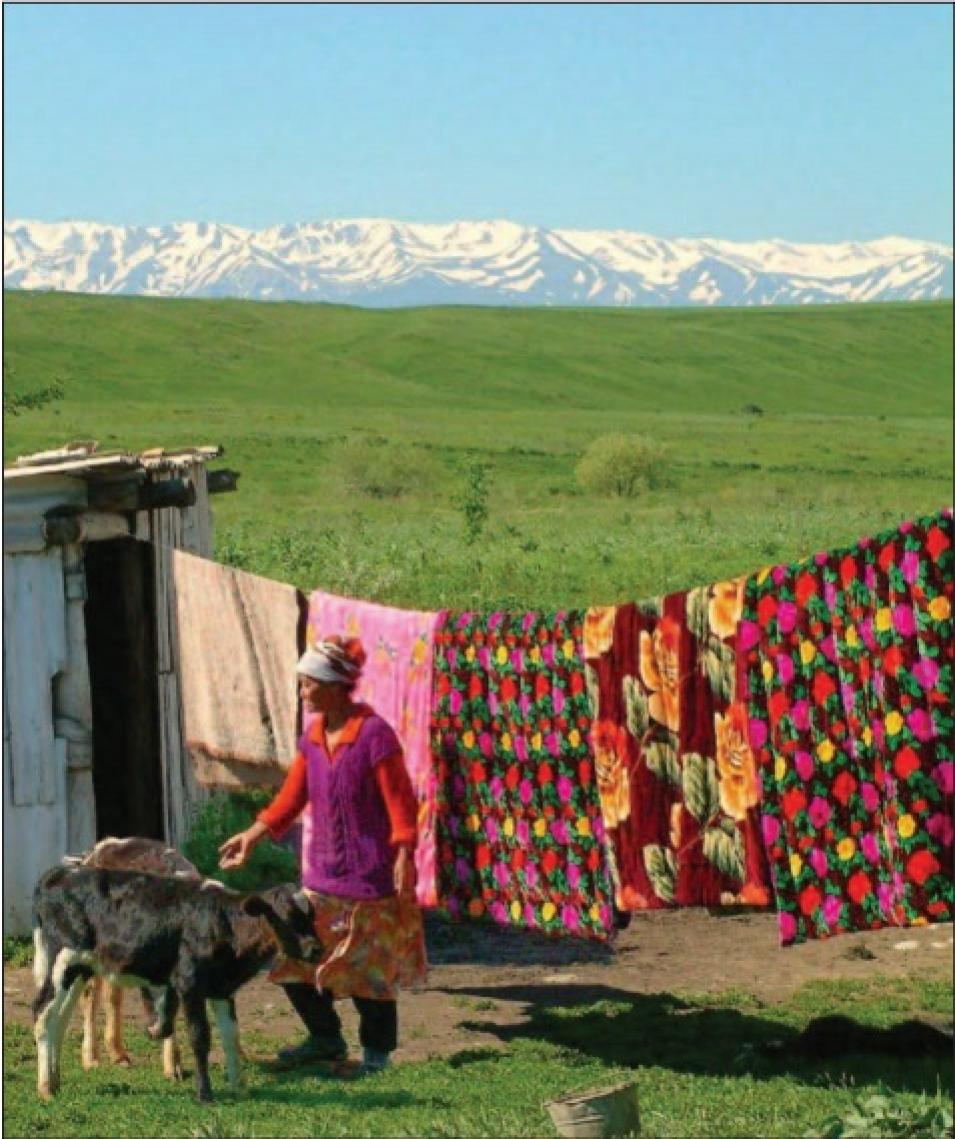

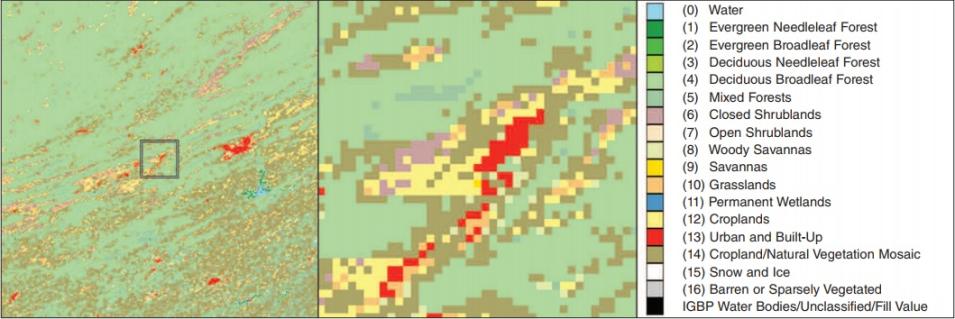

De Beurs has a radar-like curiosity for detecting all kinds of disturbances in satellite data, piqued during her own doctoral work, a study of Kazakhstan after the former Soviet Union fell apart in 1991. De Beurs said, “We asked, what is the effect of the collapse of the Soviet Union on land use? You can take the concept that the political collapse is an ecological disturbance, too. We can see evidence of land use in remote sensing data, when things green up and brown down. I wondered if we could see the changes in land use that we heard were occurring there, using satellite vegetation data.” Rapid social change had driven farmers to abandon agriculture and migrate to cities. Her interest in the topic continues, as she currently prepares for a more detailed, multi-year study of Russian agriculture, which is projected to decline due to an expected 29 percent population decline by 2050.

Plant and animal evidence

Typical of her all-angles approach, de Beurs’ upcoming Russian study will integrate field, satellite, demographic, and socioeconomic data. It was de Beurs’ integrative approach to phenology that opened new ways of thinking for Belote. De Beurs proved how studies can be conducted with satellite data and computer, as well as notebook and pencil, even for a subject as small as the gypsy moth. De Beurs said, “The gypsy moth larva eats leaves until trees are almost bare.” The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument, on NASA’s Aqua and Terra satellites, could detect the defoliation by sensing leaf reflectance, but the window is small. “The trees refoliate within the same growing season; that makes it hard to track what’s happening,” she said.