Life on the Brink

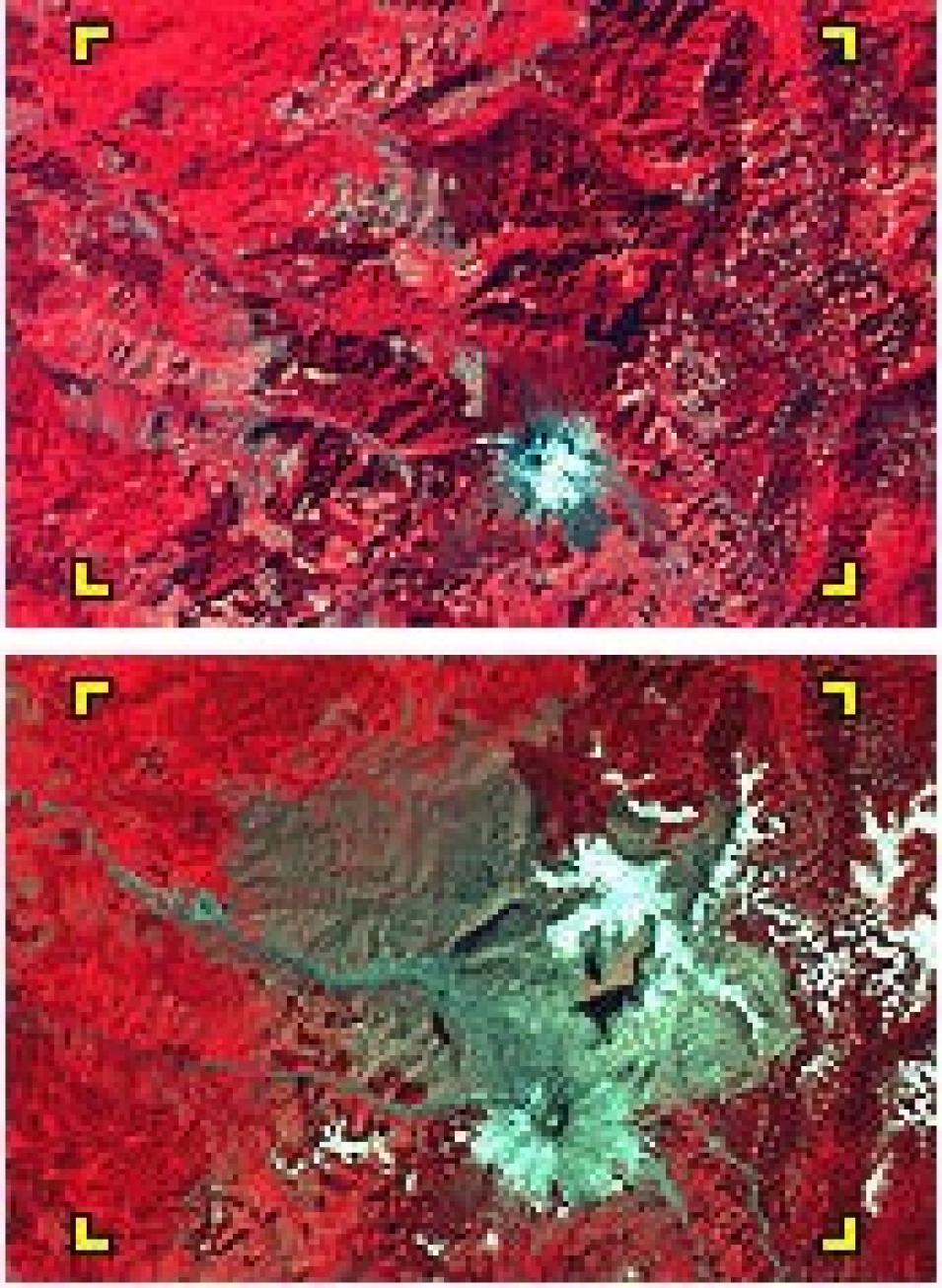

Within a few minutes, the May 18, 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens devastated more than 150 square miles of forest. As these Landsat images — from September 15, 1973 (top) and May 22, 1983 (bottom) — illustrate, the eruption produced lasting ecosystem changes. Forested areas appear in red; ash, mudslides, and mud-laden rivers show as grayish blue. (Images courtesy of USGS: Earthshots).

Fertile soil, comfortable climate, good views, and an easy commute are factors people consider when determining where to live. If the benefits are attractive enough, they often outweigh the costs—including risks from natural hazards—as demonstrated by the sheer numbers of people living near fault lines and along frequently storm-buffeted coasts.

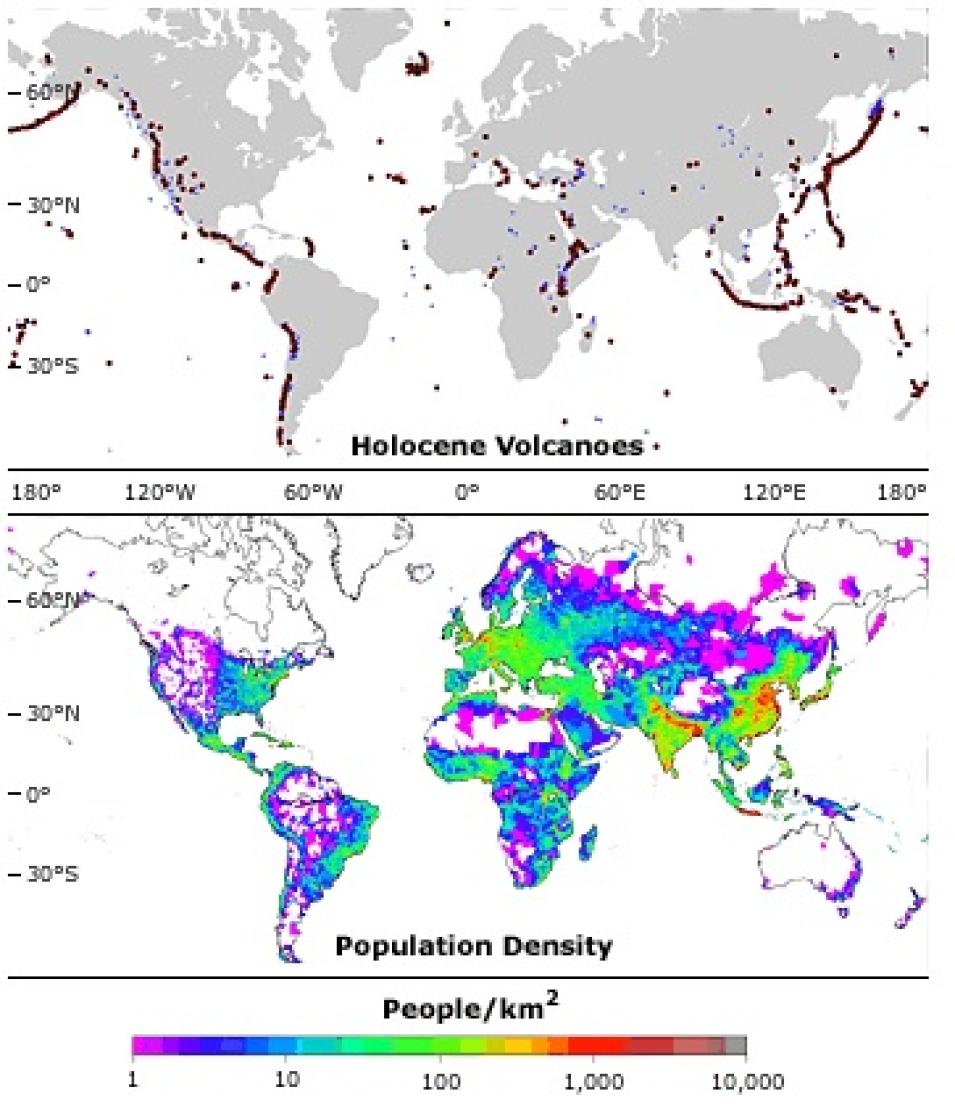

The question of hazards and population preferences arose for Christopher Small of Columbia University and Terry Naumann of the University of Alaska as they studied undersea volcanoes in the Indian Ocean. How many people live on and near terrestrial volcanoes? Neither scientist had seen an estimate and both were curious to know if such areas are sparsely or densely populated.

Small set out to find a quantifiable answer to this question using NASA's Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC) new Gridded Population of the World (GPW) data set, and a catalog of active volcanoes compiled by the Smithsonian Institution.

Volcanically active regions and dense populations often coincide, as shown by the distribution of volcanoes based on data from the Smithsonian Institution (top) and population density based on the SEDAC GPW data set. (Images courtesy of Christopher Small and Terry Naumann).

"It was straightforward to take a database of active land volcanoes, merge that with the population data, and calculate how many people lived in these areas and at what distances," said Small. "Volcanoes tend to be population-magnets, which isn't news to volcanologists, of course. Soils around volcanoes are nutrient-rich, and are periodically resurfaced by recurrent eruptions and ashfalls."

In the tropics, volcanoes have an added climatic advantage because they're at higher elevations resulting in noticeably cooler temperatures than occur at sea level. Because they typically rise above the surrounding landscape, volcanoes create their own weather, rains occur more frequently, consequently these areas tend to be very good for farming.

Using SEDAC's GPW data set, Small and Naumann produced the first study with quantitative estimates of the spatial distribution of population living on active volcanoes. Small believes it might be the only one to show that population density actually decreases with distance from a volcano.

"If a volcano is quiescent for anything approaching a generation, people tend to think that a catastrophic event probably won't happen to them," said Small. In the case of tropical volcanoes, where good farmland is limited, Small and Naumann found that people are willing to risk eruptions.

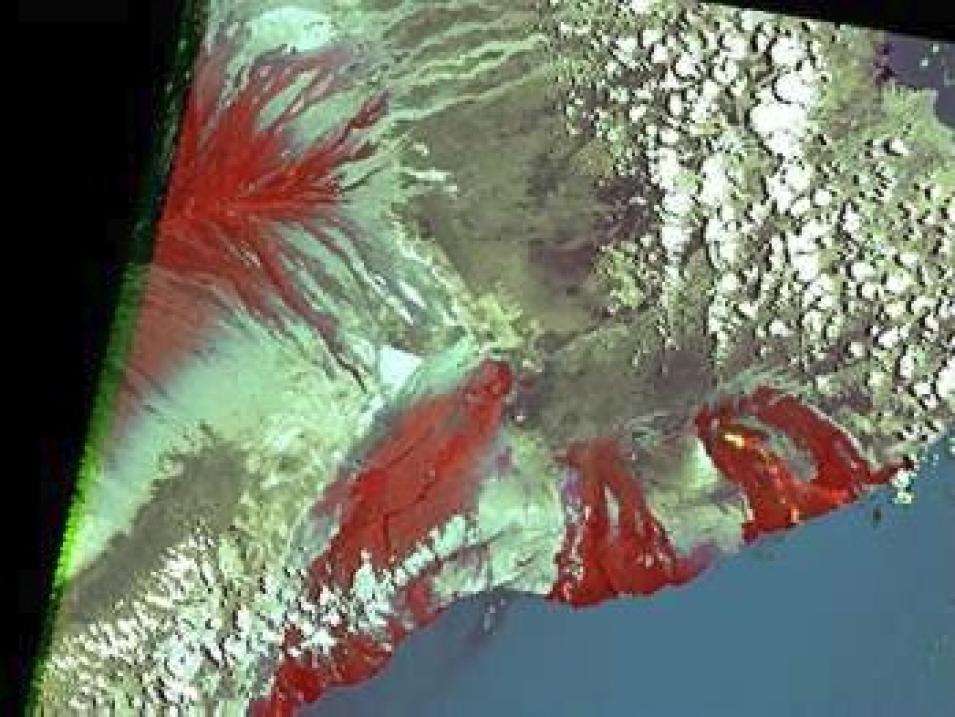

In this false-color composite image of Mount Kilauea, red indicates solidified rock from previous lava flows. The small yellow patches indicate a subterranean river of molten rock.

"I don't think that any of our findings were shocking in terms of new ideas but I haven't found other studies that accurately quantified population distributions in volcanic regions worldwide," said Small. "Many of these areas are sites of rapid growth, especially in developing countries, such as Indonesia, the Philippines, and Central America. All things being equal, if more people live in a hazardous area, the consequences of eruptions may become more severe."

References

Hartmann, J. 1998. A Linguistic Geography and History of Tai Meuang-Fai [Ditch-Dike] Techno-Culture. Journal of Language and Linguistics. 16(2):67-100.

For more information

NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC)

Gridded Population of the World (GPW)

| About the data used | ||

|---|---|---|

| Data | Active Volcano Database Gridded Population of the World (GPW) | |

| Parameter | population distributions near volcanoes | |

| DAAC | NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC) | |