João Lucas da Silva Araújo lies on a u-shaped nursing pillow next to his year-old, twin sister Ana Vitória. Though the same size as his sister, João acts like a newborn—suckling and clenching his fists with closed eyes. Green tape, a form of physical therapy treatment to relax muscles, circles his mouth and covers the back of each little finger like a green skeleton. His sister prods his face, alert and smiling.

João was the first baby in Brazil believed to be identified with Zika-related microcephaly, a brain defect associated with a small head and brain that causes cognitive and physical disabilities, even death. Once the medical community recognized that the rapidly spreading Zika virus was linked to microcephaly, a global health crisis emerged.

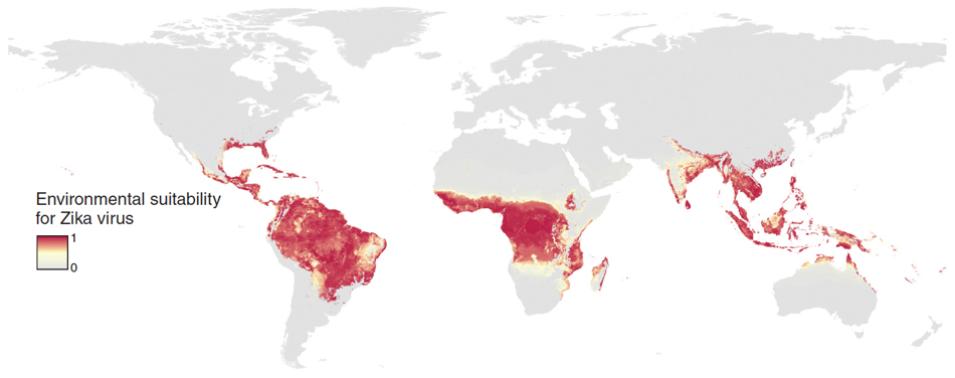

Zika appears to attack fetal brain cells key for brain development, but why one twin was spared highlights how much is not yet understood about transmission. Undeniable, however, is the culprit in Zika’s spread: the mosquito. A group of scientists at the University of Oxford had already followed this villain while pursing dengue fever. Now once more, they gathered in computer labs to offer their support. “When the outbreak was at its peak, we felt it was important to get some maps out,” said Janey Messina, a researcher from the university’s School of Geography and the Environment. The team wanted health officials to be one step ahead by providing them with maps of potential Zika outbreaks.