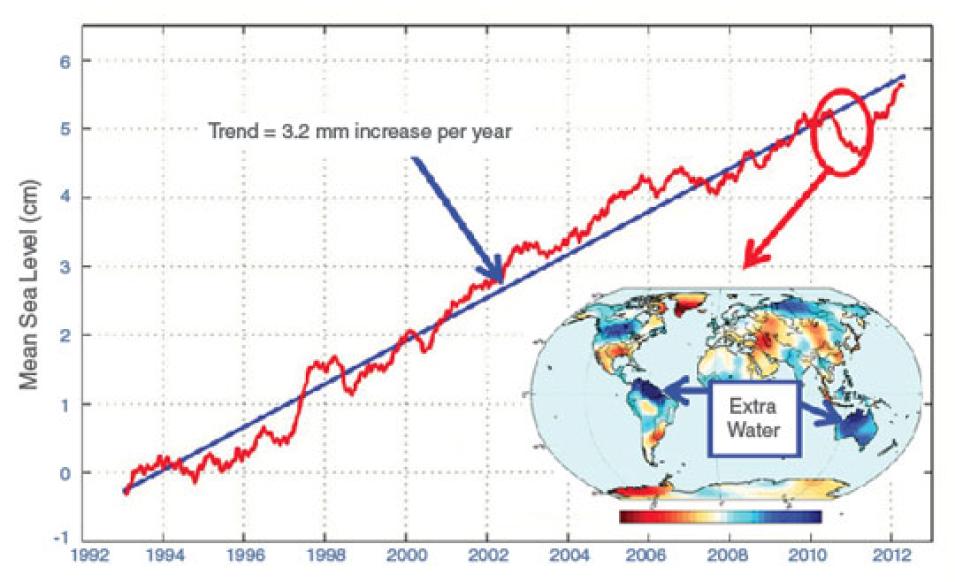

“Sea level is one of the most important yardsticks for measuring how humans are changing the climate,” said Josh Willis, an oceanographer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). He and colleague Carmen Boening have watched sea level creep upward at a slow but steady three millimeters per year. “We pay a lot of attention to this number,” Willis said, “so it was kind of surprising in 2010 and 2011 when we saw a dip, a reversal.” Sea level had suddenly dropped a half centimeter. What caused the drop? And did it mean sea level was no longer rising?

Heat versus movement

Scientists long thought that global ocean levels changed primarily in response to temperature. Willis said, “We thought that sea level changes were simply the ocean heating up and expanding or cooling and shrinking.” As global temperatures have increased, the oceans have expanded, ice has melted, and sea levels have crept upward. Low-lying island nations like Tuvalu in the South Pacific are already losing ground as rising seawater erodes coastlines and contaminates fresh inland water supplies.

But global oceans are also governed by shifts between El Niño and La Niña, a large-scale climate pattern in the Pacific Ocean. Called the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), this cycle has far-reaching impacts. A strong El Niño phase can cause drought as far away as Canada and Europe, and La Niña can send torrents of rain halfway around the world to Bangladesh. During the warmer El Niño phase, warm water pools in the eastern Pacific. The resulting impact on the jet stream fosters warm, dry weather around much of the globe. During the cooler La Niña phase, the eastern Pacific cools, changing the jet stream so that it carries wet and cool weather to many regions.

South American sailors documented this pattern more than one hundred years ago, noticing changes in water temperature along the coast of Ecuador and Peru. The oceans swing between the two phases about every three to five years. Such a pulse of heat and movement in the oceans is nothing out of the ordinary. However, the 2010 La Niña was the strongest in eighty years, devastating parts of Colombia, South Africa, Southeast Asia, and Australia with heavy rain and flooding. So scientists wondered if La Niña was behind the sea level drop. Boening said, “This drop could have two reasons. Either the ocean was cooling a lot, or there was less water in the ocean.” Could ENSO cool and shrink oceans enough to create a half-centimeter drop? If not, did the shift between El Niño and La Niña somehow move that much water out of the ocean?