When biologist Michael James captured and tagged his first leatherback sea turtle off the eastern coast of Canada in 1999, he was pursuing a mysterious animal. No one knew why Atlantic leatherbacks appeared in the frigid northern waters each year. In fact, researchers knew little at all about leatherbacks, except that they were endangered.

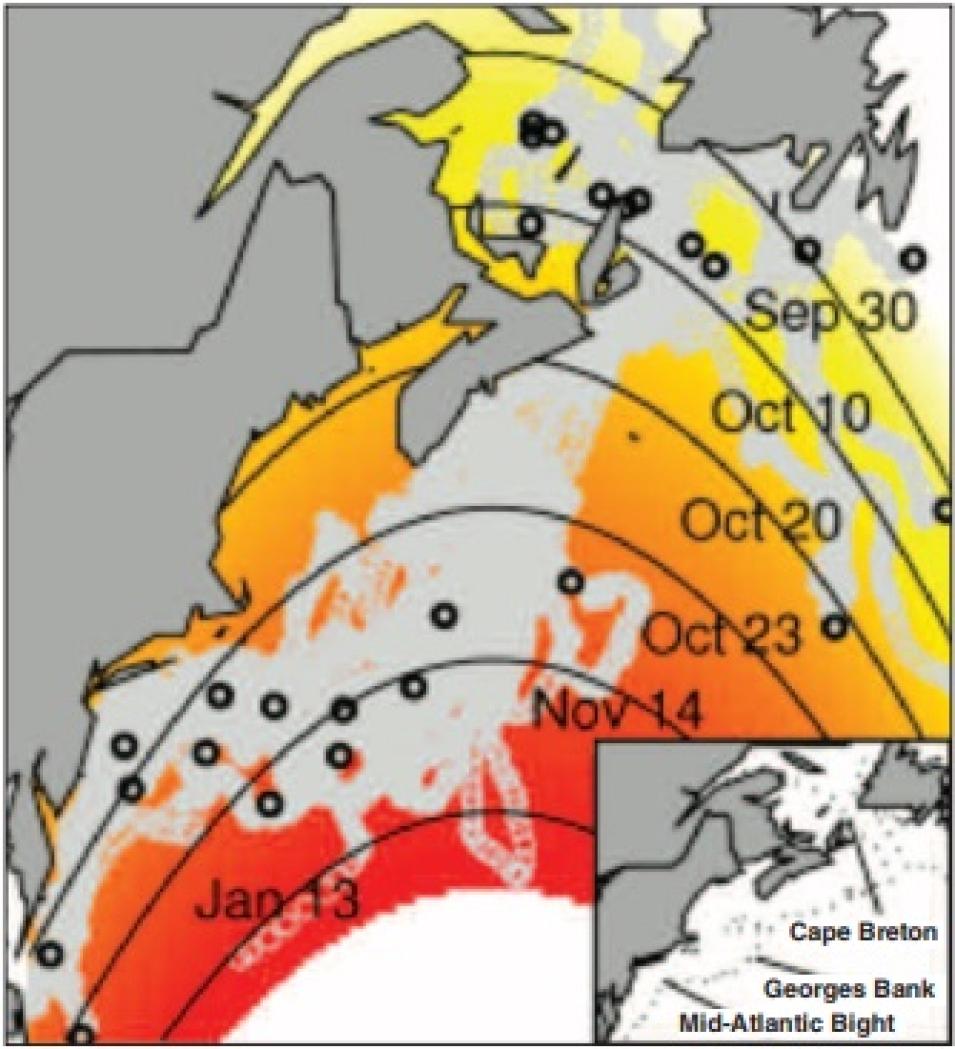

“This animal was, and remains, an enigma,” James said. “Although fishermen had known for a long time that leatherbacks had been sighted off Canadian coasts, these were considered incidental reports.” James, then a graduate student at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada, had begun studying leatherbacks with one satellite-linked transmitter attached to a turtle. Long thought to be tropical creatures, the records that James and his colleagues collected suggested otherwise: leatherbacks spent up to five months foraging in Canadian waters before migrating south. Now, more than ten years later, James has tracked over sixty turtles by satellite. Tagging and tracking leatherbacks exposed their behavior and yielded new insights about leatherback biology. But James didn’t yet know what triggered their movements. To discover the answer, he and his colleagues turned to environmental satellite data.