During the summer season of 2004, monsoon rains swelled rivers in India, Bangladesh, and Nepal, killing more than 1500 people and displacing millions. Flooding lasted for weeks, inundating thousands of villages and leaving half of Bangladesh under water.

Annual monsoon rains occur every year in Southeast Asia and other parts of the world, but it's difficult to predict how much rain will fall on specific areas, or which rivers will flood. Because periodically flooded soil is so fertile, people use the land during the dry seasons to grow crops and raise livestock. If emergency workers and aid organizations knew in advance which areas might be flooded, they could develop more effective evacuation and flood-response plans for the millions of people who farm floodplains.

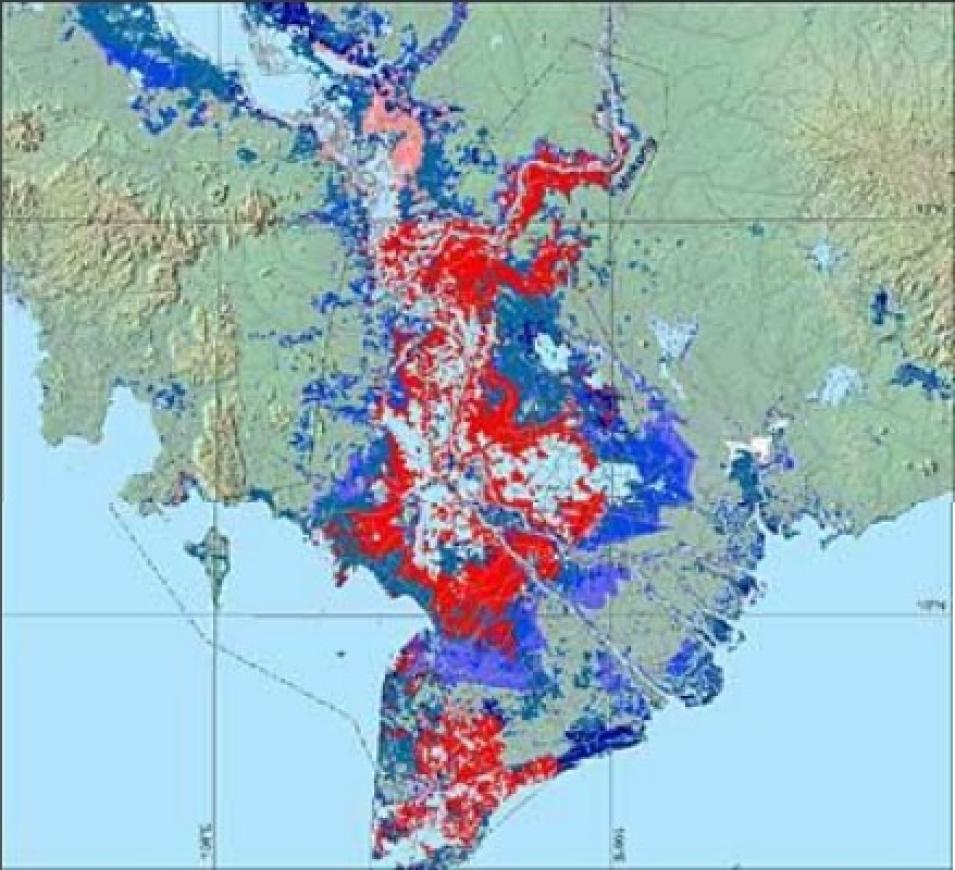

While flood prediction is not yet possible, a growing archive of satellite imagery is allowing scientists to go where aid workers can't. With satellite data, scientists can map floods remotely and piece together long-term trends that will reveal a global picture of flooding.

Fluvial geomorphologist Bob Brakenridge first tested the idea of using satellite imagery to map flooding when the Mississippi River overflowed its banks in 1993. With images from the European Space Agency's ERS-1 satellite in hand, he flew over the river valley and found that the flood extent in the satellite images matched the flooding he saw on the ground. Realizing that it was possible to map floods using satellite data, he established the Dartmouth Flood Observatory (DFO), which tracks floods worldwide and archives related information and data.

As satellite technology became more sophisticated, Brakenridge began using imagery from NASA's Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), obtained from the MODIS Rapid Response web site and NASA's Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center (GES DISC). He also uses a QuikSCAT data product developed by Son Nghiem and archived at NASA's Physical Oceanography Distributed Active Archive Center (PO.DAAC).

Although MODIS wasn't specifically designed to observe water levels, Brakenridge said it's the perfect tool. "Before the era of satellite remote sensing, and particularly before MODIS, there was no way to map flooding over large regions," he said.

Because of MODIS' 1-kilometer resolution, the sensor is unable to identify smaller rivers and flood events. But, according to Brakenridge, the wide-area coverage is invaluable for mapping floods. "Some of these flood events affect very large areas. A satellite with high spatial resolution isn't very useful if it means you need 30 scenes to get a complete image of the flood," he said.