Dr. Robert Wright, Director of the Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

Research Interests: The remote sensing of active volcanoes, including the development of systems for autonomously detecting eruptions from space, the retrieval of eruption parameters from satellite data such as lava effusion and flow cooling rates, and measuring the composition of gases emitted by volcanoes using mid- and long-wave infrared measurements; the development of hyperspectral imaging sensors; the use of cube satellites for Earth remote sensing, including the detection of volcanic eruptions and gas emissions.

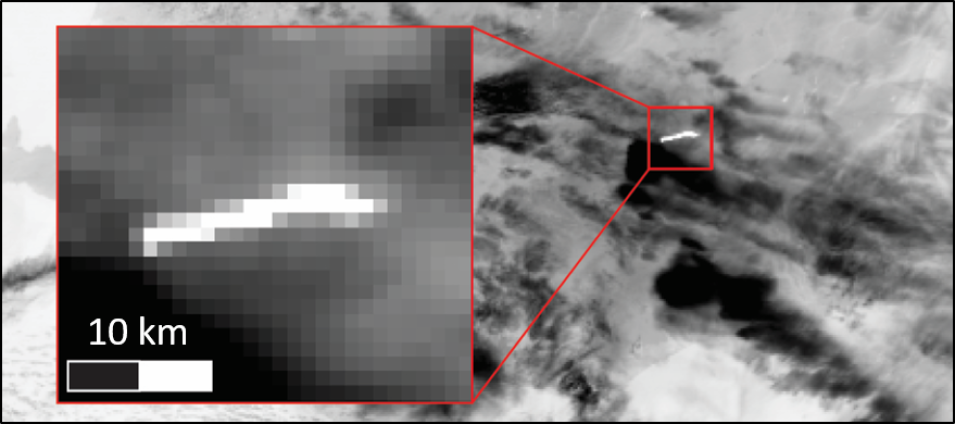

Research Highlights: Twenty years ago, in October 2001, a volcano in the remote South Sandwich Islands known as Mount Belinda began lobbing ash into the sky and spitting lava from its summit. Had the eruption occurred three years earlier, it might not have been detected for weeks or even months. However, because NASA’s Terra satellite was then orbiting the Earth (launched December 18, 1999) and carrying the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument, a team of researchers at the University of Hawaii almost 9,000 miles away knew about it less than 24 hours after it started.

It’s estimated that there are more than 1,500 potentially active volcanoes around the globe, and 500 of them are said to be active at any given time. Traditionally, scientists have kept tabs on active volcanoes with ground-based observation tools, but the use of Earth-observing geostationary and polar-orbiting satellites is quickly becoming the primary method of monitoring Earth’s volcanic activity. Thanks to on-going advances in satellite instrumentation and new methods of data analysis, scientists can now monitor volcanic activity in the most isolated parts of the globe, detect changes in the atmosphere and Earth’s surface that suggest an eruption may be imminent, and even predict when an eruption will end by tracking its lava flow rate.