This post highlights a peer-reviewed journal article discussing the synergy of urban heat, pollution, and social vulnerability in Houston, Texas. The article is an outgrowth of a data story, Aerosols and Their Impacts on Houston, TX, published on the NASA Visualization, Exploration, and Data Analysis (VEDA) dashboard. VEDA uses Earth science data for storytelling through visual exploration of data that are transformed into cloud-native formats. Two of the VEDA dashboard thematic areas are environmental justice and air pollution.

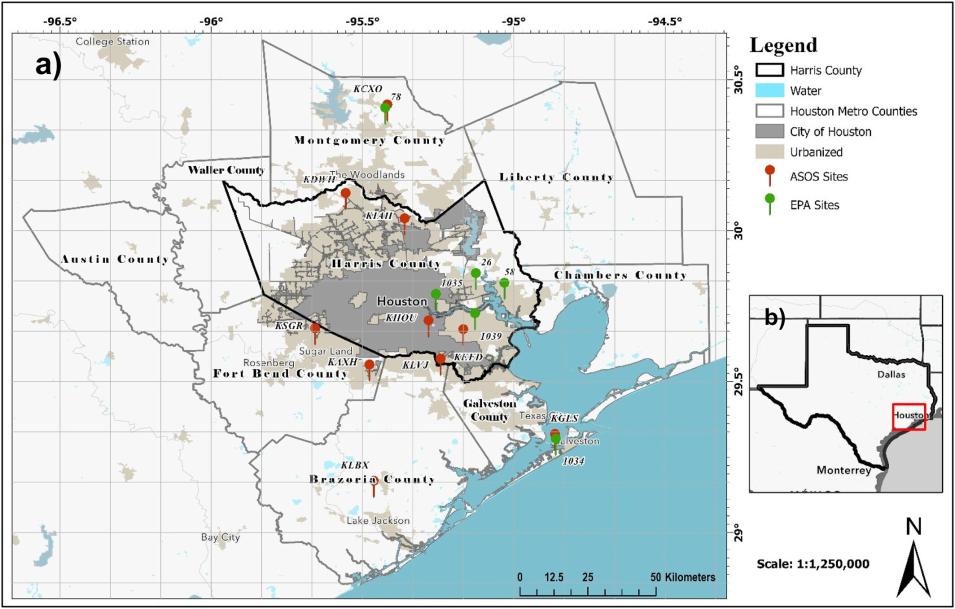

Andrew Blackford, a graduate student in the Department of Atmospheric and Earth Science at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, used NASA Earth science data products to visually explore the relationship between heat, air pollution, and social vulnerability in the Houston metropolitan area over the first two decades of the 21st century. After the publication of the story on VEDA, he and his co-authors conducted an in-depth analysis that led to the peer-reviewed journal publication.

Urban Heat Islands and Pollution

Houston, one of the largest metropolitan areas in the United States, has experienced remarkable urban growth over the past two decades. This expansion has seen the addition of approximately 1,345 square kilometers of developed land—an area nearly twice the size of New York City—to the Houston metropolitan area (HMA). However, with this rapid growth comes a set of environmental challenges that are becoming increasingly difficult to ignore.

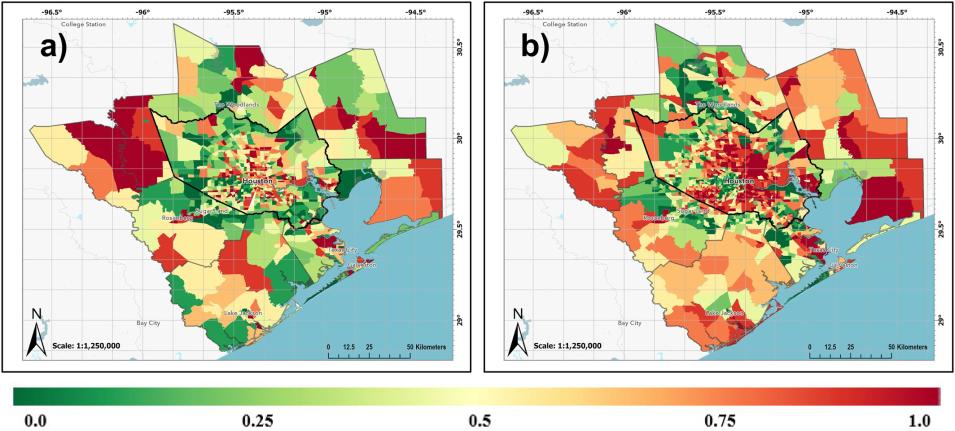

As Houston has grown, so too has the urban heat island (UHI) effect—a phenomenon where urban areas are significantly warmer than their rural surroundings. An analysis by Blackford and his co-authors found that as the city expanded, the UHI effect also spread, even affecting areas that were already developed prior to 2000. This has resulted in higher maximum and minimum air temperatures across the city.

Alongside the UHI effect, urban pollution islands (UPI) also have become a concern. While overall particulate pollution in the HMA has decreased over time, urban areas have seen less significant reductions compared to rural regions. In particular, changes in air quality in urban areas have shown greater variability, with more uniform and sharp reductions during the latter part of the study period.

Although the Clean Air Act Amendment of 1990 contributed to reductions in particulate pollution, the increase in vehicle traffic and other urban growth-related factors seems to have offset some of these gains. This aligns with similar studies that have identified local air pollution pockets in the HMA, which are not always detected by existing air quality monitoring networks.