Initially, Linkie used camera traps to study tigers, since traps have proven efficient in thick jungle foliage. “The rainforest is really, really dense, so when you go walking through you can’t really deviate off the main trails,” Linkie said. “So a lot of these rainforest mammals, the large-bodied ones, tend to stick to the same trails.” Installing camera traps along these established trails enables researchers to remotely monitor a variety of species in ways that were not previously possible.

While scanning for tigers in trap photographs, Linkie realized traps could also track the somewhat neglected Malayan tapir. “In Latin America, tapirs are one of the best studied mammal species,” he said. In Asia, however, tapirs tend to be disregarded in favor of more charismatic animals such as rhinoceroses or elephants. “The Malayan tapir needs champions,” Linkie said.

In spite of their elusive nature, the tapir’s role in forest ecology is important. “They are very effective seed dispersers,” said Patrícia Medici, chair of the Tapir Specialist Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Malayan tapirs eat about 115 different species of fruits and plants. As they roam throughout their territory, they deposit the undigested seeds in their dung. “We know that the absence of tapirs has a huge impact on the diversity and structure of the forest,” Medici said.

Tracking tapir occupancy

Researchers have been using camera traps to track everything from tigers to poachers, so thousands of them are installed across Southeast Asia. Linkie and his thirty-six colleagues needed to narrow down the most likely sites. Since Malayan tapirs prefer the dense jungle understory, the researchers analyzed data from NASA's Space Shuttle Radar Topography (SSRT) Mission, revealing elevation and slope of the land. Other data were used to indicate forest and river edges. They also looked at forest fire data from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument that could serve as a proxy for deforestation to decide whether certain trap sites might hold tapirs.

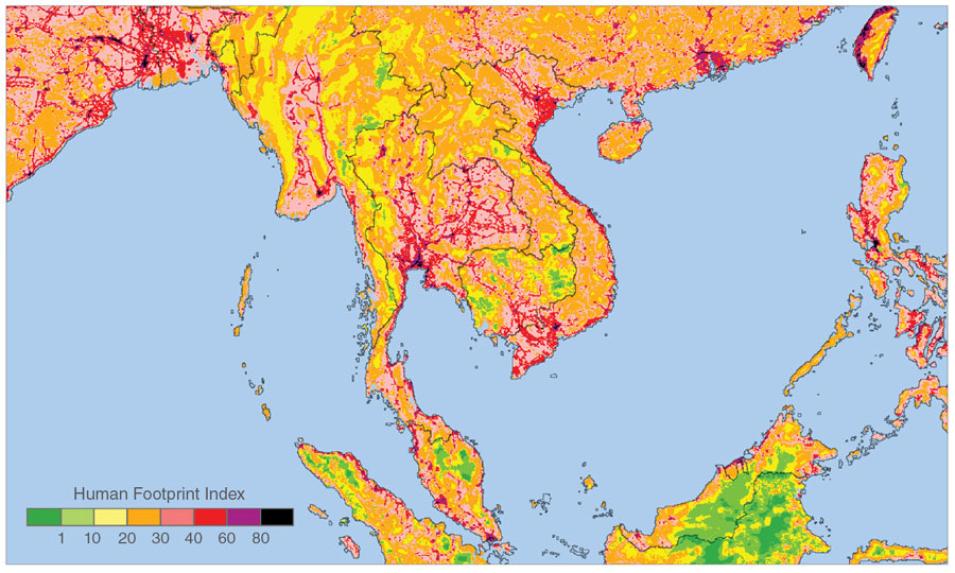

To map human activity, Linkie used the Human Footprint Index. Linkie had never used the index before, but it is well known within conservation circles, he said. Archived at NASA's Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC), the index features human population densities and elevations, land use, travel routes, villages, and coasts. The higher the index, the more human disturbance there is. “When you look at patterns of change around these landscapes,” Linkie said, “they all tend to emanate out of these areas with higher index, meaning areas that might be at lower elevation, might be closer to roads, or might be closer to villages.”

After choosing nineteen sites containing a total of 1,128 camera traps, Linkie looked for tapirs in photographs taken between 1997 and 2011. The sites spanned protected conservation parks and unprotected areas in Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Indonesian island of Sumatra. It was impossible to tell whether the traps captured snapshots of different tapirs each time or the same tapir over and over. But what the photographs could show was overall tapir “occupancy,” revealing which areas tapirs occupied, and which they did not.