Oceanographer and engineer Stefan Talke had become a kind of historian. In the U.S. National Archives and at other archives around the world, he searched out forgotten tide gauge records of the Pacific Ocean and North America. The records date as far back as the mid-1800s. Some had been digitized; others were still sitting in boxes. He photographed old paper graphs and logbooks, and his students at Portland State University helped tabulate the records.

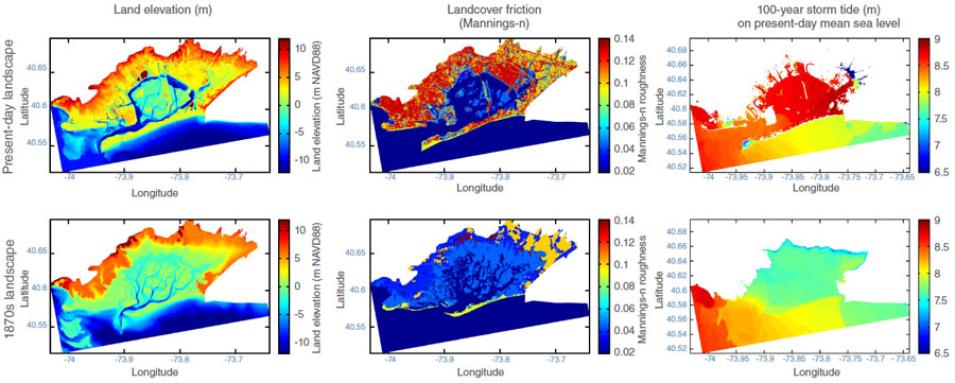

The tide level measurements strung from ports in Florida and up the U.S. East Coast into Canada, then from Alaska down the U.S. West Coast and along the Pacific Rim from Japan to New Zealand. The data would help reconstruct a history of sea levels, and extreme storms that pushed tide levels up. Like other researchers, Talke wanted to be able to measure how tide levels had changed, and how much of the change might be caused by a warming climate or by how people have modified estuaries—the places where fresh and salt water meet—to better suit their uses. When he ran into oceanographer Philip Orton at a conference in 2012, he was headed to the New York City branch of the National Archives to hunt for more tide records, and agreed to look for storm records for Orton too.

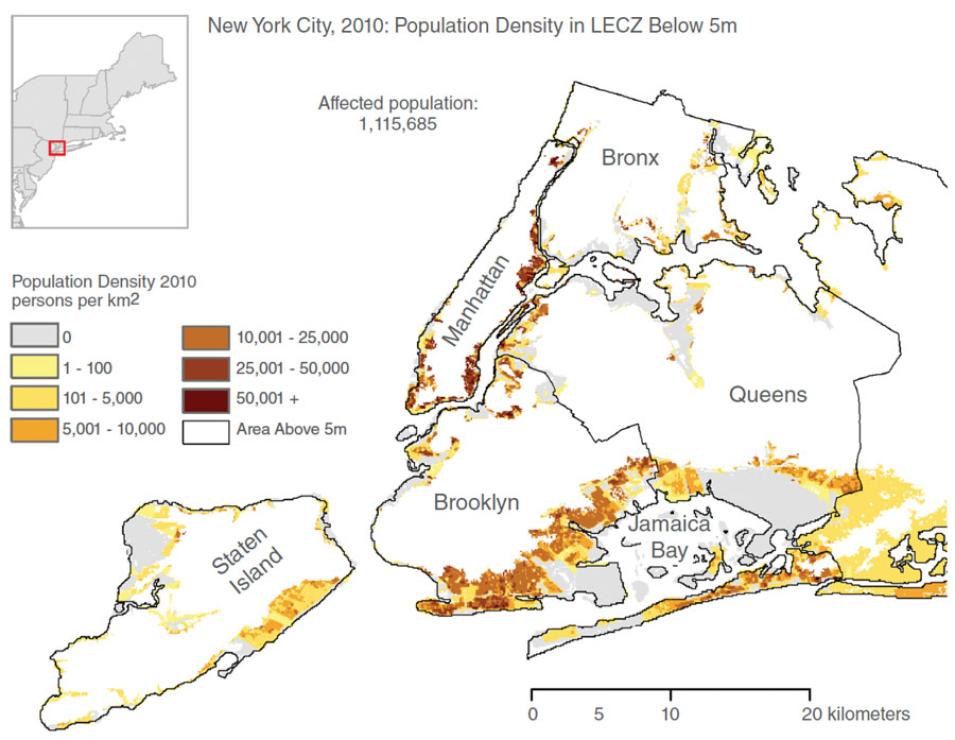

The data would help them sooner than they thought, and in unexpected ways. Two months later, Hurricane Sandy drowned the New York and New Jersey coasts in a catastrophic storm surge. Orton, who lives and works in the area, immediately shifted his focus to how he as a scientist could help. “Before Sandy we were saying storm risks will get worse in the future,” Orton said. “Suddenly my job went from talking about what might happen in the future, to helping people see how they could ameliorate it.” And during this time Orton and Talke began to see the past as part of a future solution.