Visit the world’s high mountain ranges and you’ll probably see less ice and snow today than you would have a few decades ago. More than 110 glaciers have disappeared from Montana’s Glacier National Park over the past 150 years, and researchers estimate that the park’s remaining 37 glaciers may be gone in another 25 years. Half a world away on the African equator, Hemingway’s snows of Kilimanjaro are steadily melting and could completely disappear in the next 20 years. And in the Alps, glaciers are retreating and disappearing every year, much to the dismay of mountain climbers, tourist agencies, and environmental researchers.

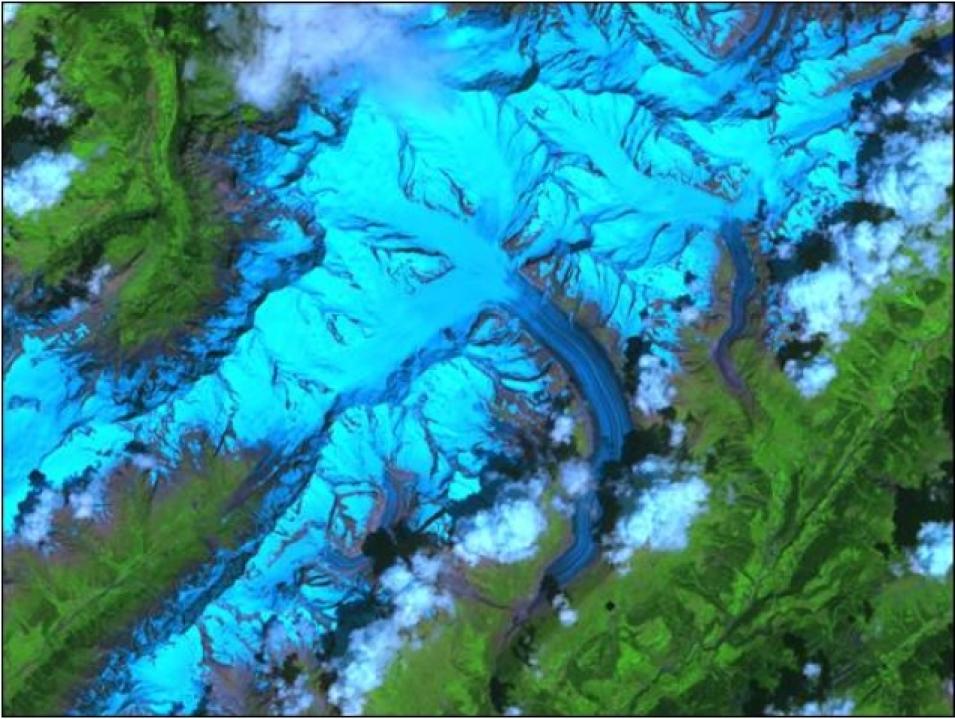

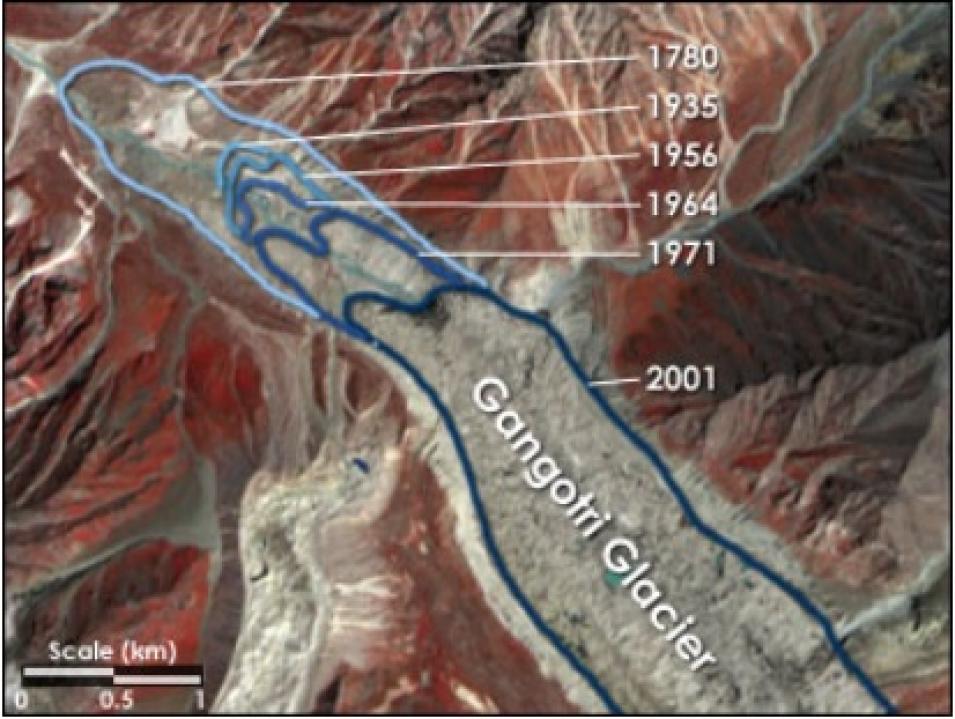

“Receding and wasting glaciers are a telltale sign of global climate change,” said Jeff Kargel, head of the Global Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS) Coordination Center at the United States Geological Survey (USGS) in Flagstaff, Arizona. Kargel is part of a research team that’s developing an inventory of the world’s glaciers, combining current information on size and movement with historical data, maps, and photos.

In response to climate fluctuations, glaciers grow and shrink in length, width, and depth. Because glaciers are sensitive to the temperature and precipitation changes that accompany climate change, the rate of their growth or decline can serve as an indicator of regional and global climate change. Tracking and comparing recent and historical changes in the world’s glaciers can help researchers understand global warming and its causes (such as natural fluctuations and human activities). Glacial changes can also have a more immediate impact on communities that rely on glaciers for their water supply, or on regions susceptible to floods, avalanches, or landslides triggered by abrupt glacial melt.