To test this, the team unveiled their results at an intensive, hands-on workshop in Cape Town, Africa in October 2011. Twenty-two researchers from eleven African countries and many different focus areas were carefully selected to be the first to work with the new, high-resolution MISR data. Scientists from a variety of agencies also contributed, including the European Space Agency and the newly formed South African National Space Agency (SANSA).

This sharing cultivated a strong partnership. With the full support of NASA, Verstraete gave SANSA the opportunity to be the first institution worldwide to run the new system and generate the new MISR data locally. SANSA has since made it a flagship program of their Earth Observation division and, with the initial help from Hunt, is adopting the processing of all MISR orbits over Africa. Soon they will be able to offer the new high-resolution MISR data not only to scientists, but to forestry managers, policy makers, and others who could benefit from the data. And that, according to SANSA chief Sandile Malinga, is of utmost priority. “One pressing issue for Africa as a whole, for instance, is food security, so monitoring drought is very, very important,” he said.

Meanwhile, scientists like Scholes and Verstraete are also eager to mine this new-found data cache for insight on nagging problems, like desertification. When drought and other conditions converge, like soil erosion, they set off a domino effect that transforms fertile land into desert. Rich, life-giving topsoil that supports crops takes centuries to build up, but just a few seasons to be blown or washed away. Famine then ensues. It is a problem that has plagued the African continent for decades and is difficult to reverse.

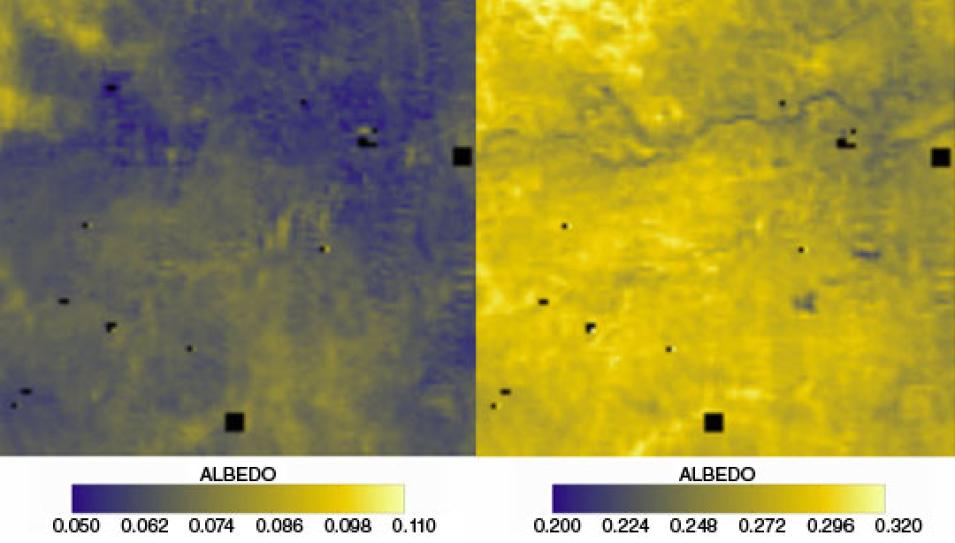

Scholes and Verstraete are optimistic about how the new measurements can help. Like the ability to detect cancer cells in a patient, pinpointing where the process begins is critical to limiting its spread. Scholes said, “We wish to get repeatable, reliable measures of ecologically important features of the land surface. That would help us answer questions such as ‘where is desertification occurring?’” With that, Scholes added, “The results allow us to track the state of the land surface in ways which are directly important to people.”

Reference

Verstraete M. M., L. A. Hunt, R. J. Scholes, M. Clerici, B. Pinty, and D. L. Nelson. 2012. Generating 275-m resolution land surface products from the Multi-Angle Imaging Spectroradiometer data. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing (99): 1–11, doi:10.1109/TGRS.2012.2189575.

For more information

NASA Atmospheric Science Data Center (ASDC)

Multi-Angle Imaging Spectroradiometer (MISR)

South African National Space Agency (SANSA)

Michel M. Verstraete

Robert J. Scholes

| About the remote sensing data used |

| Satellite |

Terra |

| Sensor |

Multi-Angle Imaging Spectroradiometer (MISR) |

| Data sets |

MISR Level 1B2 Terrain Top of Atmosphere (TOA) |

| Resolution |

275 meter |

| Parameter |

Spectral and directional reflectance |

| DAAC |

NASA Atmospheric Science Data Center (ASDC) |

The photograph in the title graphic shows scientists Bob Scholes (left) and Michel Verstraete (right) collecting data from a monitoring station in a subtropical evergreen succulent thicket in Eastern Cape province, South Africa. This highly endangered but species-rich ecosystem is being restored after decades of degradation. New, high-resolution MISR data will help estimate how this restoration affects the global climate.(Courtesy R. Scholes/Council for Scientific and Industrial Research [CSIR], South Africa)