In late April 2002, a cold front pushed eastward across the midwestern United States. Ahead of the cold front, a powerful thunderstorm formed over Maryland, spawning what was perhaps the state’s worst tornado. With winds estimated at over 260 miles per hour, the tornado touched down and traveled a path of destruction for 24 miles (39 kilometers), claiming several lives and injuring more than 100 people. The thunderstorm associated with this tornado persisted from the Appalachian Mountains to the Atlantic Ocean, causing an estimated $120 million in damages.

Lightning Spies

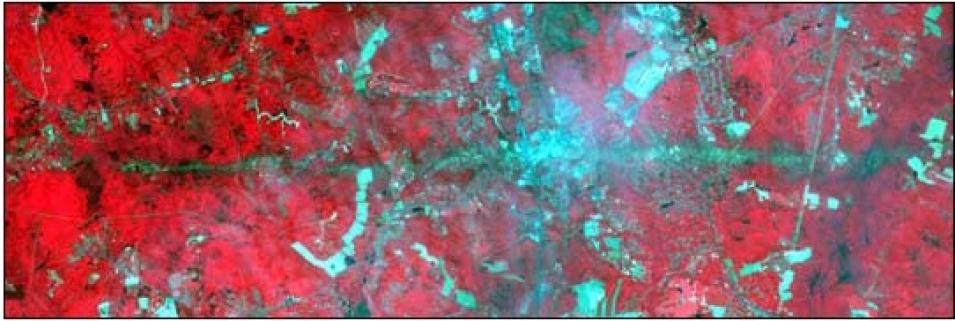

ASTER captured this image of La Plata, Maryland on May 3, 2002. Several days earlier, the La Plata Tornado carved a 24-mile path through the state. In this image, vegetation appears in red, and bare fields and urban areas appear in green. The turquoise swath across the middle of the image shows the tornado’s path.

Tornadoes are just one consequence of thunderstorms. Lightning strikes, flash floods, and downdrafts from collapsing storms all threaten lives and property. One of the best defenses against thunderstorm hazards is effective prediction. Predicting storms accurately, however, requires a thorough understanding of electrical storm life cycles.

In 1997, NASA launched the Lightning Imaging Sensor (LIS) aboard the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite. The LIS detects and maps the distribution and variability of cloud-to-cloud, intracloud, and cloud-to-ground lightning. “Lightning measurements alone don’t tell you everything you need to know about thunderstorms, but if you can relate lightning to the severity of the storm, then you have something forecasters can use,” said Richard Blakeslee, senior research scientist at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. “To complicate matters, the instruments in space can only ‘see’ lightning signals above a certain strength; below that, the pulses are too small to detect. So how much lightning are we missing?” Hoping to answer this and other questions, Blakeslee organized the ALTUS Cumulus Electrification Study (ACES).

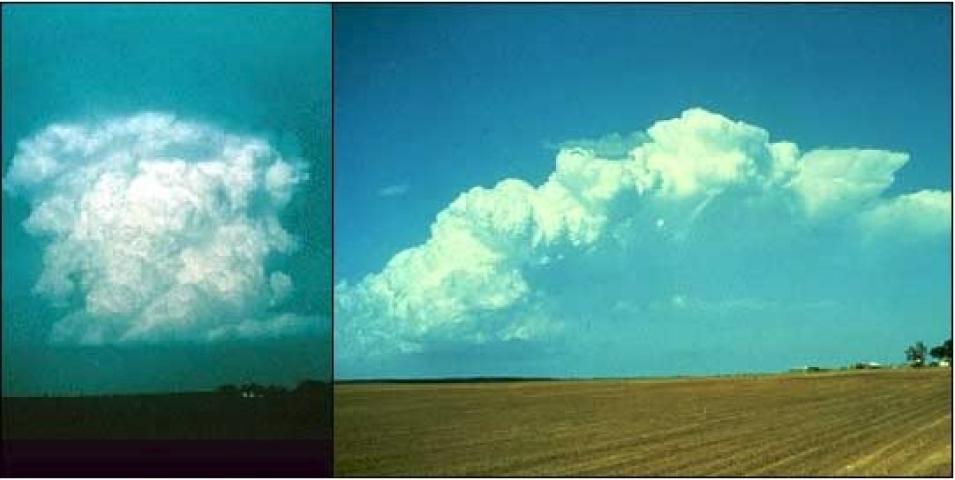

The image on the left shows a single-cell thunderstorm. Single-cell storms may last 20 to 30 minutes, and are usually not strong enough to cause severe weather. The image on the right is a more typical multicell thunderstorm, which may last for several hours and produce severe weather. (Images courtesy ofNOAA/NSSL).

With a primary goal of validating LIS data, the ACES project examined thunderstorms in the Florida Everglades region over a four-week period in August 2002. Key to the study was the ALTUS II, an uninhabited aerial vehicle capable of flying at high altitudes for long durations. Especially useful to ACES was ALTUS II’s ability to fly at relatively slow speeds, between 70 and 100 knots, or approximately 70 miles (113 kilometers) per hour. “The aircraft’s slow speed was important because we desired a plane that could observe a thunderstorm continuously,” said Blakeslee.

The most common thunderstorms consist of multiple storm cells (air masses fed by warm, moist rising air). At its peak, a storm cell receives warm air and produces rain or hail. When the supply of upward-moving warm air stops, the storm cell collapses, and the resulting downdrafts feed new storm cells that repeat the process. While a thunderstorm might persist for hours, individual storm cells generally last from only 10 to 30 minutes. “A high-speed plane flies over a storm in about 2 minutes then takes up to 15 minutes to turn around and come back, giving you 2-minute observations separated by 15-minute gaps. And 15 minutes later, you’re looking at a different storm cell,” said Blakeslee. “But ALTUS II could make tight turns, still within measurement range of about 5 kilometers, and come back over the storm repeatedly. Since the plane stayed within measurement range, we didn’t miss any of the storm’s evolution.”

Observing a storm's development can help forecasters better monitor a thunderstorm's rapidly changing behavior. Despite the rain or hail they may produce at their peaks, collapsing storm cells sometimes pose the greatest danger. Mature storms produce downdrafts, and while some downdrafts are nothing more than gentle breezes, others are hazardous. “If there’s a rotation in the storm, a strong downdraft can foster the development of a tornado. Sometimes the cold air in a storm cell descends at a high velocity and spreads out at the ground in what’s called a microburst. If a plane flies into a microburst and the pilot reacts incorrectly, he can lose control of the plane. Once microbursts hit the ground, they can be almost as severe as tornadoes, producing straight-line winds that blow roofs off buildings,” Blakeslee said.

Another aim of the ACES study was to determine how lightning rates might help predict thunderstorm hazards. “We often see lightning jumps, where the lightning rate increases dramatically then suddenly decreases, and these jumps often precede severe weather on the ground. If the lightning measurements can be combined with other measurements, like radar, then we might be able to anticipate which storms will rapidly intensify and need to be watched very closely,” said Blakeslee.

During the ACES experiment, the aircraft carried electrical, magnetic, and optical sensors to measure lightning activity and the electrical environment around thunderstorms. “The ALTUS II was a very effective platform,” said Bill Farrell, Blakeslee’s co-investigator at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “Prior to the mission we were concerned the ALTUS would make so much electromagnetic noise that it would interfere with our observations, but it was really quiet. We could detect storms with our instrumentation long before the aircraft reached them.”

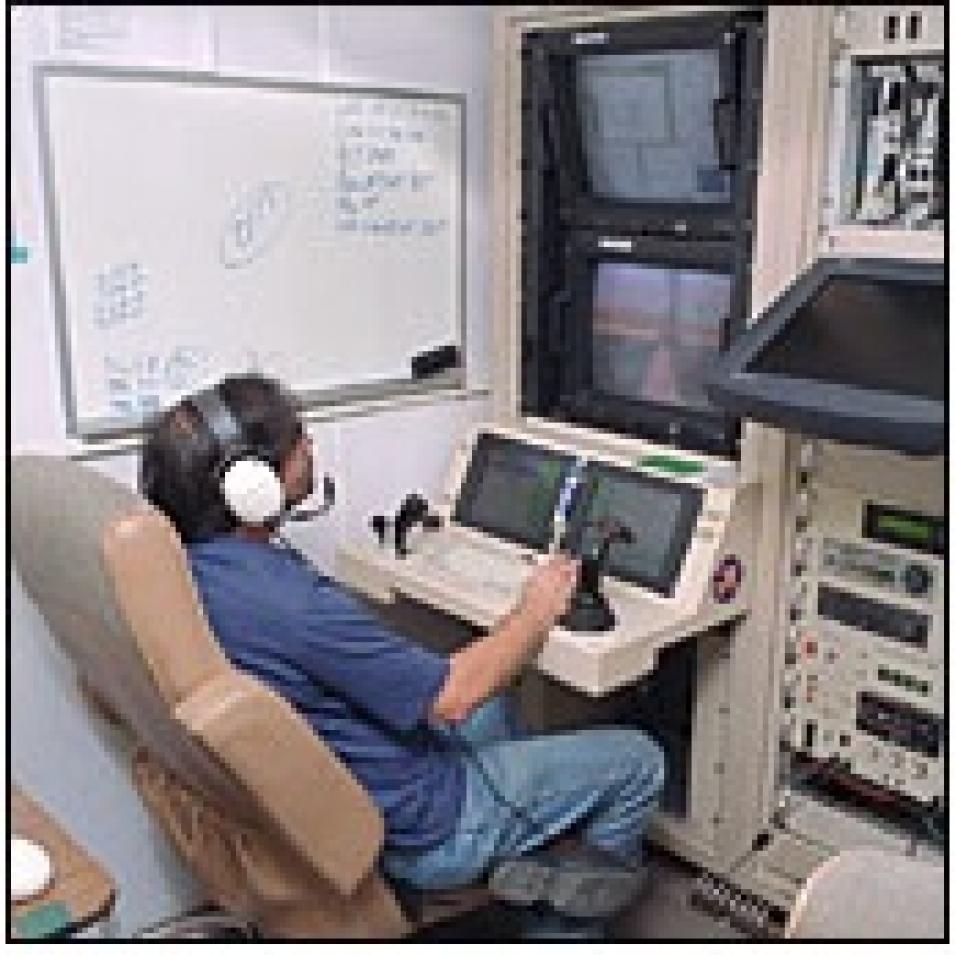

An overriding concern throughout the ACES experiment was safety. “In most airplanes, the pilot is assumed to have ‘see and avoid’ capability to keep from colliding with other planes,” Blakeslee said. Uninhabited aerial vehicles are equipped only with cameras, whose images must be interpreted by someone at a remote location. For this reason, the ACES experiment’s flight area included only the sparsely populated Florida Everglades and nearby ocean, and the ALTUS II was flown above 40,000 feet to keep it separated from commercial aircraft. “Our plane was flown remotely by a pilot in the control center who could respond to the camera’s images and aircraft flight data. So it could also be called a remotely piloted vehicle, but we still had to be extra cautious.” Throughout the experiment, the researchers took care to fly the plane over and near thunderstorms, but never into them.

Sprites can extend from the tops of clouds to the ionosphere, an ionized layer 56 miles (90 kilometers) above the Earth’s surface. This image of red sprite lightning was taken on November 11, 1995. (Image courtesy of Astronomy Picture of the Day, D. Sentman, G. Wescott, Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, NASA).

In addition to the practical concern of improving severe storm predictions, the ACES study looked at the global electric circuit and the Sun-Earth connection.

Bounded by the Earth’s surface at the bottom and the ionosphere at the top, the global electric circuit surrounds the Earth in an electric field of up to 100 volts per meter. Scientists have long known that thunderstorms feed this circuit, but the details are still poorly understood. Farrell said, “When a thunderstorm is not discharging lightning, it behaves like a battery; when it is discharging lightning, it behaves like a radio antenna. Previous global electric circuit models usually considered only the battery mode, but we’ve found that for short periods of time — anywhere from once per second to once per minute — the radiated power actually exceeds the battery-like power. So we’re trying to figure out how this affects the global electric circuit.”

References

ACES Description Document (adapted from papers given at the AIAA First Technical Conference and Workshop on Unmanned Aerospace Vehicles, Systems, Technologies, and Operations, May 20-23, 2002, Portsmouth, VA; and the Technical Applications and Analysis Center UAV Conference, October 28-30, 2002, Santa Fe, NM).

ACES Executive Summary and Science Plan. Accessed April 30, 2003.

For more information

NASA Global Hydrometeorology Resource Center Distributed Active Archive Center (GHRC DAAC)

Altus Cumulus Electrification Study

| About the remote sensing data used | ||

|---|---|---|

| Platform | Tropical Rainfall Measurement Mission (TRMM) | ALTUS II |

| Sensor | Lightning Imaging Sensor (LIS) | various electrical, magnetic, and optical sensors |

| Parameter | storm life cycles | storm life cycles |

| DAAC | NASA Global Hydrometeorology Resource Center Distributed Active Archive Center (GHRC DAAC) | GHRC DAAC |