“Ten to 15 years ago, the climate modeling community was working with global models that used only ocean and atmosphere data,” Kabat said. “At that time, the community believed the climate system was driven by just those two components. Five to seven years ago, some of the largest climate centers began incorporating vegetation data into their models, but they were assuming only one vegetation type per continent. All of Europe, for example, was classified as having one vegetation type. Slowly but surely, ISLSCP has helped climate modelers recognize the importance of accurate data for land components. That was not the case 10 years ago, but now it’s widely accepted.”

Established in 1983 under the United Nations Environment Programme, ISLSCP promotes the use of satellites to develop data sets of land surface parameters for use in climate models. Forrest Hall, senior research scientist at the University of Maryland Joint Center for Earth Systems Technology, is the principal investigator in this project. “One element of ISLSCP involves very large-scale field experiments to develop and test our methods for understanding the Earth’s ecosystems and how they interact with the atmosphere to influence climate. Another important aspect is taking measurements in the field to validate satellite data,” he said.

The First ISLSCP Field Experiment took place on the Konza Prairie in Kansas between 1987 and 1989 and provided satellite-derived data on land-surface states and processes. Building on that work, the Boreal Ecosystems-Atmosphere Study examined the Canadian boreal forest from 1994 to 1996.

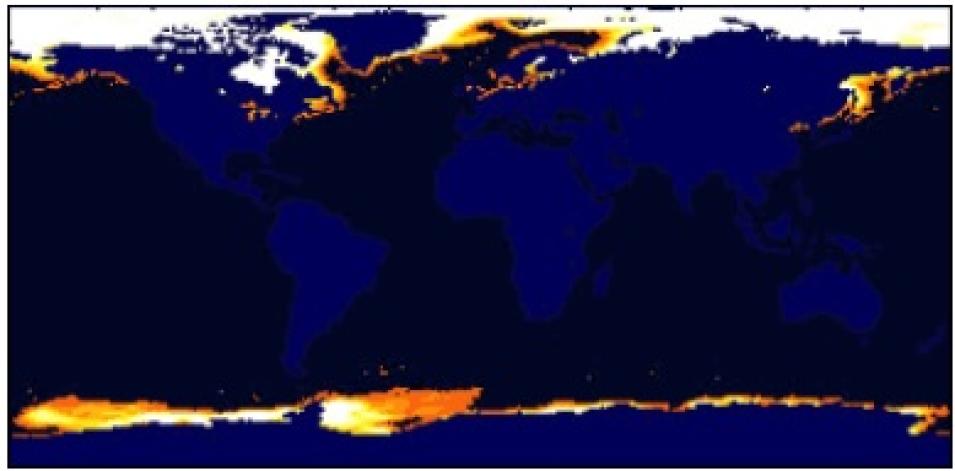

ISLSCP has progressed in stages, consisting of three different initiatives. In 1995, Initiative I published CD-ROMs of global land cover, soil, hydrometeorology, and radiation data. “Climate modelers typically use a latitude/longitude grid, and the ISLSCP data are all in a consistent grid format,” said Richard Armstrong, an ISLSCP researcher and senior research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, one of NASA’s Distributed Active Archive Centers (DAACs). The Initiative I data sets cover a two-year period, 1987 and 1988, but the longer the time span, the greater the benefit to the models. “It’s good to look at data covering at least 10 to 20 years,” said Armstrong.

Due for release in 2003, Initiative II has expanded coverage, with data spanning at least 10 years (1986 to 1995) and even longer for selected data sets. Initiative II also improved on the spatial and temporal resolutions of Initiative I and used updated algorithms.

“Initiative III will pick up where Initiative II left off,” Hall said. “First, we’ll extend it in time through 2007. Second, we’ll add new data sets that have just recently become available as a result of new satellites or new analysis techniques. Finally, we may go back and reprocess some of the Initiative II data sets with newer algorithms.”

Continual improvements to data sets and algorithms may sound excessive, but the satellite record spans only 30 years, and scientists are just beginning to understand all the factors that affect global climate change. “We often don’t have much luck predicting the weather five days out,” said Armstrong. “Climate modeling and prediction is still a pretty new field.”