As human population in coastal areas increases each year, the need to improve hurricane forecasting mounts. From Texas to Maine, more than 44 million people currently reside in coastal counties and barrier islands, and weekend and holiday tourists often increase that number significantly, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

In the Eyewall of the Storm

"The hurricane community has made great strides in accurate forecasting and tracking, but knowing how intense a storm is going to be when it hits the shoreline is a key factor," said Robbie Hood, of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center Global Hydrology and Climate Center (GHCC) and principal investigator for the Convection and Moisture Experiment (CAMEX).

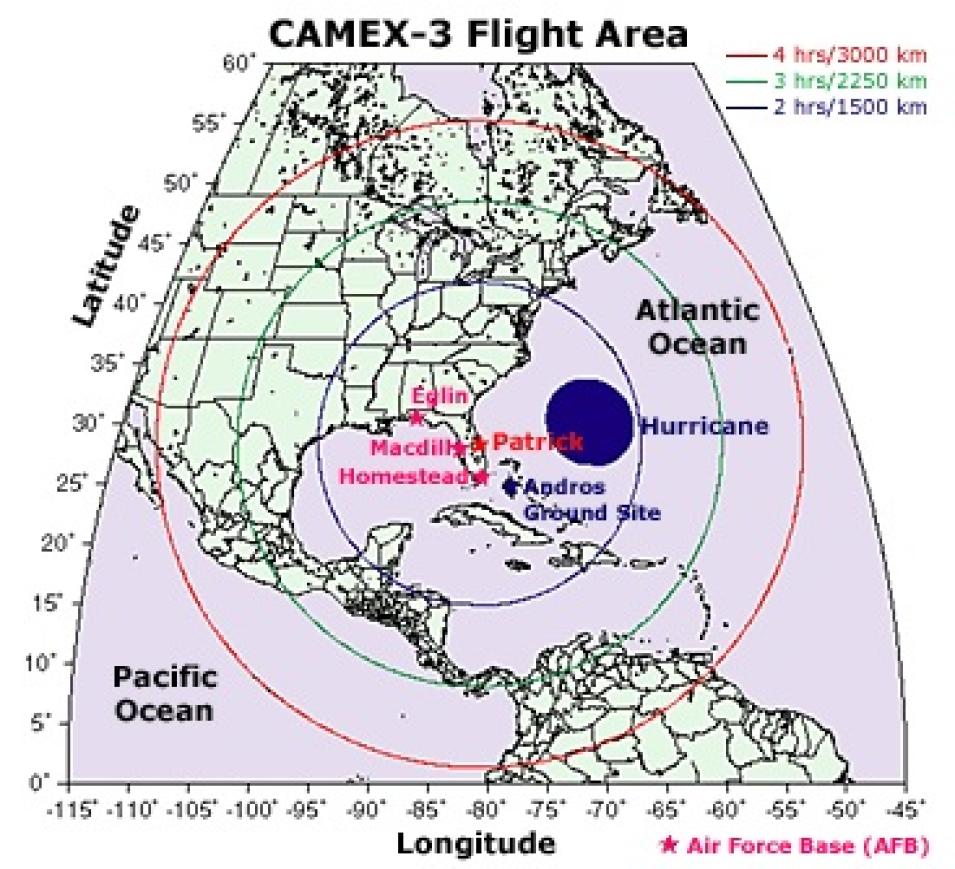

The first two CAMEX missions, conducted at Wallops Island, Virginia in 1993 and 1995, were designed to study atmospheric and precipitation processes using aircraft, balloon, and land-based remote sensing instruments. CAMEX-3 turned its focus to hurricane tracking and intensification.

With a greater understanding of the intensification process, scientists can improve predictive computer models that might someday help forecasters decrease the radius of coastal evacuation areas and increase warning time for evacuation of those areas.

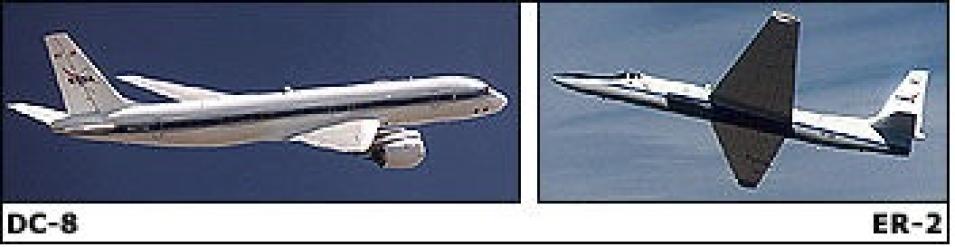

The U.S. Air Force Hurricane Hunters and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) routinely fly into tropical storms to gather data that indicate potential storm strength and size and help pinpoint landfall locations. However, storm hunters typically only get to see a storm's lower altitudes.

"We only know what goes on in the bottom half of a hurricane, from sea level to about 27,000 feet," said Hood. "CAMEX-3 enabled us to learn about these storms from top to bottom."

With three NOAA aircraft and a NASA ER-2 and DC-8, the CAMEX-3 team embarked on a comprehensive study of Hurricane Bonnie on August 23, 1998. The DC-8, a jetliner designed to carry scientific instruments rather than passengers, was equipped with instruments that measure temperature, pressure, and humidity. The ER-2, a modified U-2, is a high-altitude research plane. Capable of flying almost twice as high as the DC-8, ER-2 carries a variety of remote sensing instruments that take measurements from the top of the storm.

"The measurements we obtained from Hurricane Bonnie are the first taken within the upper region of a hurricane," said Gerald Heymsfield, Research Meteorologist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center and CAMEX-3 mission scientist.

CAMEX-3's sophisticated instrumentation suite, sponsored by NASA Headquarters' Atmospheric Dynamics and Thermodynamics Program, included radar, visible and infrared sensors, laser-based instruments, and dropsondes — miniature transmitters that broadcast meteorological measurements via radio signals.

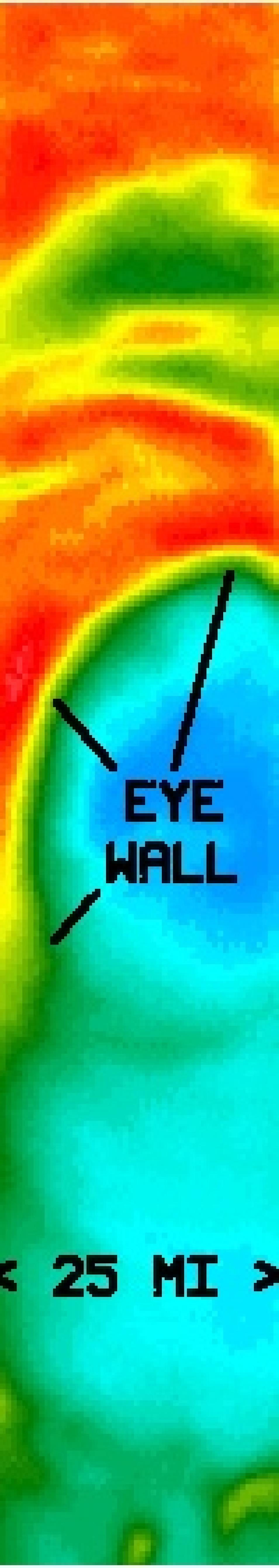

"We brought NASA satellite and remote sensing technology into the picture to give hurricane researchers data from high altitudes where their aircraft don't fly," said Hood. In particular, the ER-2 Doppler Radar (EDOP) aboard the ER-2 provided vastly improved resolution measurements of Bonnie's eyewall, Heymsfield said.

The aircraft also carried instruments designed to measure moisture and wind fields around the hurricane. Representing cutting edge technology, the Multicenter Airborne Coherent Atmospheric Wind Sensor (MACAWS) measures both horizontal and vertical winds, critical to understanding a hurricane's potential path.

The annual period of peak hurricane occurrence in the Atlantic is approximately mid-August to late September. Once a hurricane develops, the CAMEX team formulates a mission plan, based on how fast and in which direction the storm is moving. "Basically, we block out a six-week window of time, travel to Florida — and wait," said Heymsfield. "We knew Bonnie was going to be a good one, and we wanted to be at ground zero when it made landfall."

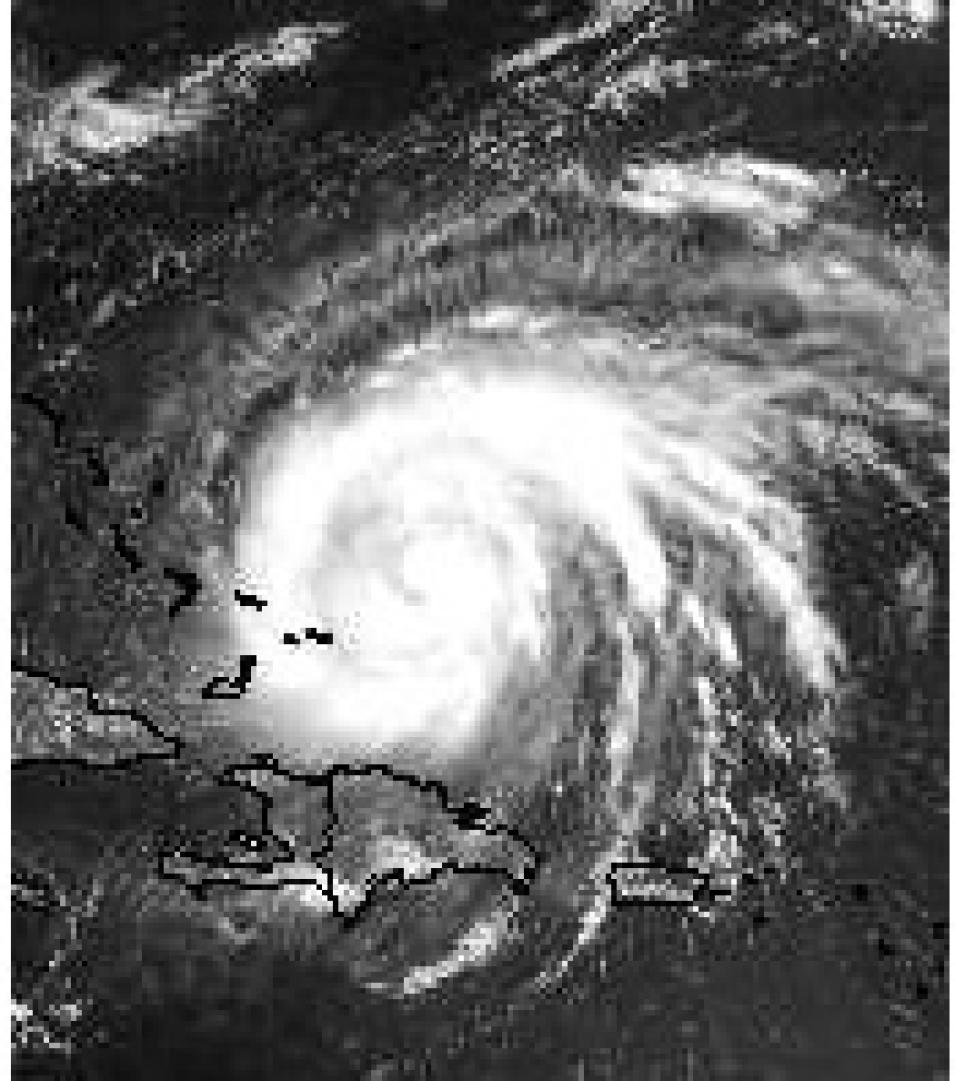

When tropical cyclones — low pressure storm systems that develop over warm tropical or subtropical waters — reach sustained winds of at least 39 miles per hour, they are designated "tropical storms" and assigned a name. A tropical storm that reaches sustained winds of at least 74 miles per hour is referred to as a "hurricane" or a "typhoon," depending on its geographical location.

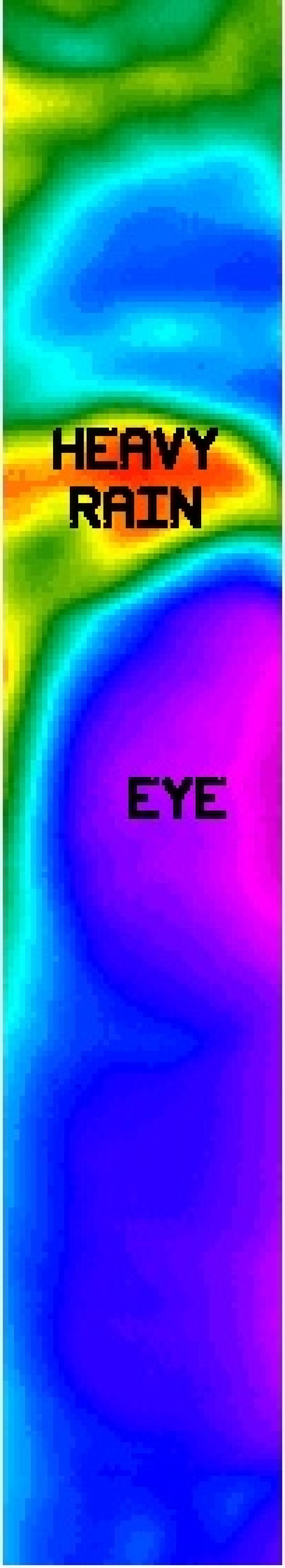

The center of a tropical cyclone, known as the eye, is a roughly circular area marked by relatively calm conditions, including light winds, little or no precipitation, and, often, clear skies. Hurricane eyes range from 8 kilometers (5 miles) to over 200 kilometers (120 miles) in diameter, but most measure approximately 30-60 kilometers (20-40 miles) across.

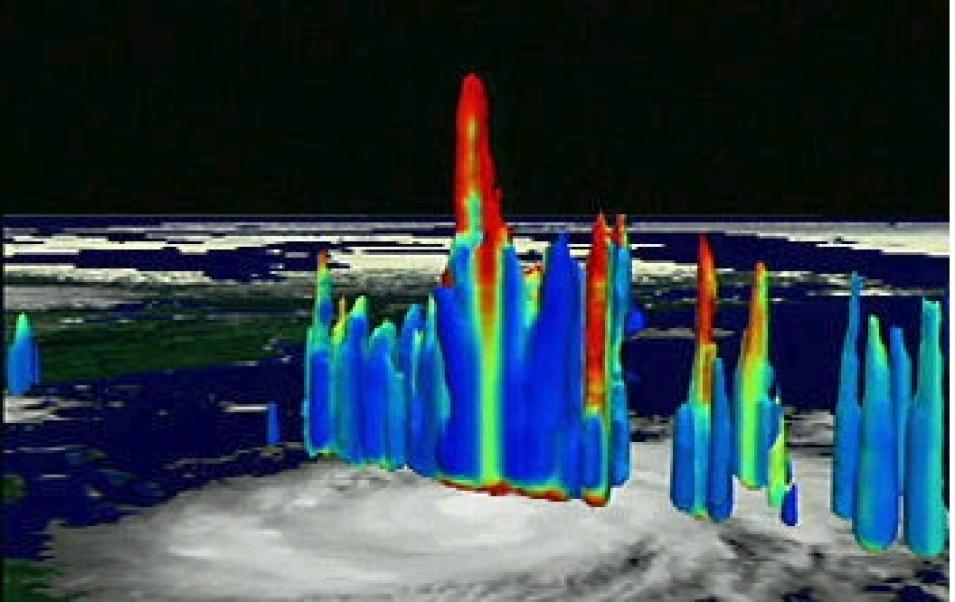

The eye is surrounded by the eyewall, the zone where surface winds reach their highest speed and where the strongest thunderstorm activity occurs. During the development stage of a cyclone, clusters of intense thunderstorms, called convective bursts, occur. A single thunderstorm within a convective burst is known as a hot tower. "One of our mission goals was to get detailed observations of the three-dimensional structure of a convective burst within Bonnie's eyewall," said Heymsfield.

According to Heymsfield, the relationship between the occurrence of convective bursts and sudden intensification of the hurricane can be significant. Through a process known as latent heating, clouds develop and the resulting convection heats the atmosphere, carrying the warm air to higher levels. "It's kind of like a feedback system that intensifies the hurricane," he said.

Hurricane Bonnie's initial intensification from tropical depression to hurricane occurred late in the day on August 20. "During the intensification period, convective bursts were noted in both the satellite observations and by the NASA aircraft pilots," the research team reported in a paper to be published in the Journal of Applied Meteorology.

"Our most significant finding is that hot towers result in strong subsidence in the eye of the hurricane," Heymsfield said. Scientists hypothesize that hot towers help create a region of warmer temperatures at the core, called a warm core, which results in lower surface pressure and a consequent intensification of winds. "If forecasters can identify a warm core in satellite imagery, they'll have a good indication that the storm is going to intensify," he said.

The idea of subsiding warm air in the hurricane's eye is not new, according to Heymsfield. "Scientists have been speculating for years about the existence of a weak sinking motion, but this is the first time it has been observed, and we actually witnessed a stronger sinking motion than we expected," he said.

Understanding hurricane dynamics at high altitudes is crucial to improved forecasting. "Until we understand some of the structural processes, it's going to be very difficult to get accurate forecasts," said Heymsfield. "The more precise data we have, the more accurate the forecasting models are going to be."

Another mission, CAMEX-4, is planned for summer 2001. "We have some new instruments that will help us understand the warm core and the convective bursts better," Heymsfield said. "We want to find out whether other hurricanes have the same type of structure that we saw in Bonnie."

CAMEX-4 will also feature a new radar on the DC-8, and a new instrument on the ER-2 that will release dropsondes from higher altitudes than in the past. "We still have a lot to learn, and we need better measurements, but as a result of CAMEX-3, we now have data-backed evidence to support our hypotheses," said Heymsfield. "Bonnie is probably one of the best-sampled hurricanes we have so far. In terms of reaching mission objectives, 1998 was a very good year for us."

References

Campbell, James B. 1987. Introduction to Remote Sensing.New York: The Guilford Press.

Heymsfield, G.M., J. Halverson, J. Simpson, L. Tian, and T.P. Bui. In press for August, 2001. ER-2 Doppler Radar (EDOP) Investigations of the Eyewall of Hurricane Bonnie During CAMEX-3. Submitted to Journal of Applied Meteorology.

CAMEX-3 News and Events https://ghrc.nsstc.nasa.gov/home/field-campaigns/camex3

National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/. Accessed June 27, 2001.

NASA, NOAA team seeks secret of hurricane's power: Convection and Moisture Experiment-3." August 12, 1998. Science@NASA. Accessed July 5, 2001.

Calibration flight planned today: CAMEX-3 status report." August 13, 1998. Science@NASA. Accessed July 5, 2001.

Hurricane Bonnie's cumulonimbus storm clouds towered 18 kilometers from the eye of the storm. The height in these images is exaggerated for clarity, and colors correspond to precipitation from blue (light) to red (heavy). (Image by Greg Shirah, GSFC Scientific Visualization Studio; Data courtesy TRMM Project).

Aircraft make second flight with TRMM: CAMEX-3 status report." August 18, 1998. Science@NASA. Accessed July 5, 2001.

Bonnie may be the one: First CAMEX-3 hurricane brewing in mid-Atlantic." August 20, 1998. Science@NASA. Accessed July 5, 2001.

Here comes Bonnie! First CAMEX-3 storm aims for Florida." August 21, 1998. Science@NASA. Accessed July 5, 2001.

West by Northwest: Bonnie now a hurricane, stays on track." August 22, 1998. Science@NASA. Accessed July 5, 2001.

Eye-to-eye, and Bonnie winks: NASA/NOAA team makes first sortie into hurricane." August 24, 1998. Science@NASA. Accessed July 5, 2001.

For more information

NASA Global Hydrometeorology Resource Center Distributed Active Archive Center (GHRC DAAC)

| About the remote sensing data used | ||

|---|---|---|

| Aircraft | ER-2 | ER-2 |

| Sensor | ER-2 Doppler Radar (EDOP) | Multicenter Airborne Coherent Atmospheric Wind Sensor (MACAWS) |

| Parameter | hurricane tracking and intensification | hurricane tracking and intensification |

| DAAC | NASA Global Hydrometeorology Resource Center Distributed Active Archive Center (GHRC DAAC) | NASA GHRC DAAC |