The grassy, high plains and rolling rangelands of Texas are perfect for grazing cattle. But the specter of drought is rarely far from ranchers’ minds. Drought desiccated Texas from 2011 to 2012 so severely that many ranchers had to purchase feed and water, and truck it out to their cattle. Others chose to sell off parts of their herds well before animals reached their peak weight—and peak prices.

Although rangelands are hardy biomes that thrive in relatively dry climates, a persistent lack of water can tip them into drought, withering grasses and reducing prairies to dust. Because ranchers rely heavily on grass, they ultimately depend on water. Rain and snow are important sources, but much of that water evaporates back into the atmosphere. The remaining water either runs off into lakes or streams, or percolates down into the soil to nourish plants where their roots are, within 5 to 100 centimeters (2 to 39 inches) of the surface.

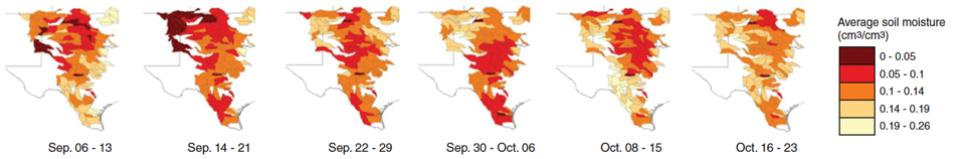

This soil moisture—or lack of it—forges a ranch’s future. “Soil moisture determines the biomass, or how much grass we’re going to get,” said Gabriel Senay, a scientist at the US Geological Survey who studies agriculture and hydrology. “And of course, the healthiness of the grass will determine how many cattle can be supported.” But soil moisture measurements that are accurate and available over broad regions have long been missing from the drought equation.