Dr. Owen Cooper, Senior Research Scientist, Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder/NOAA Chemical Sciences Laboratory

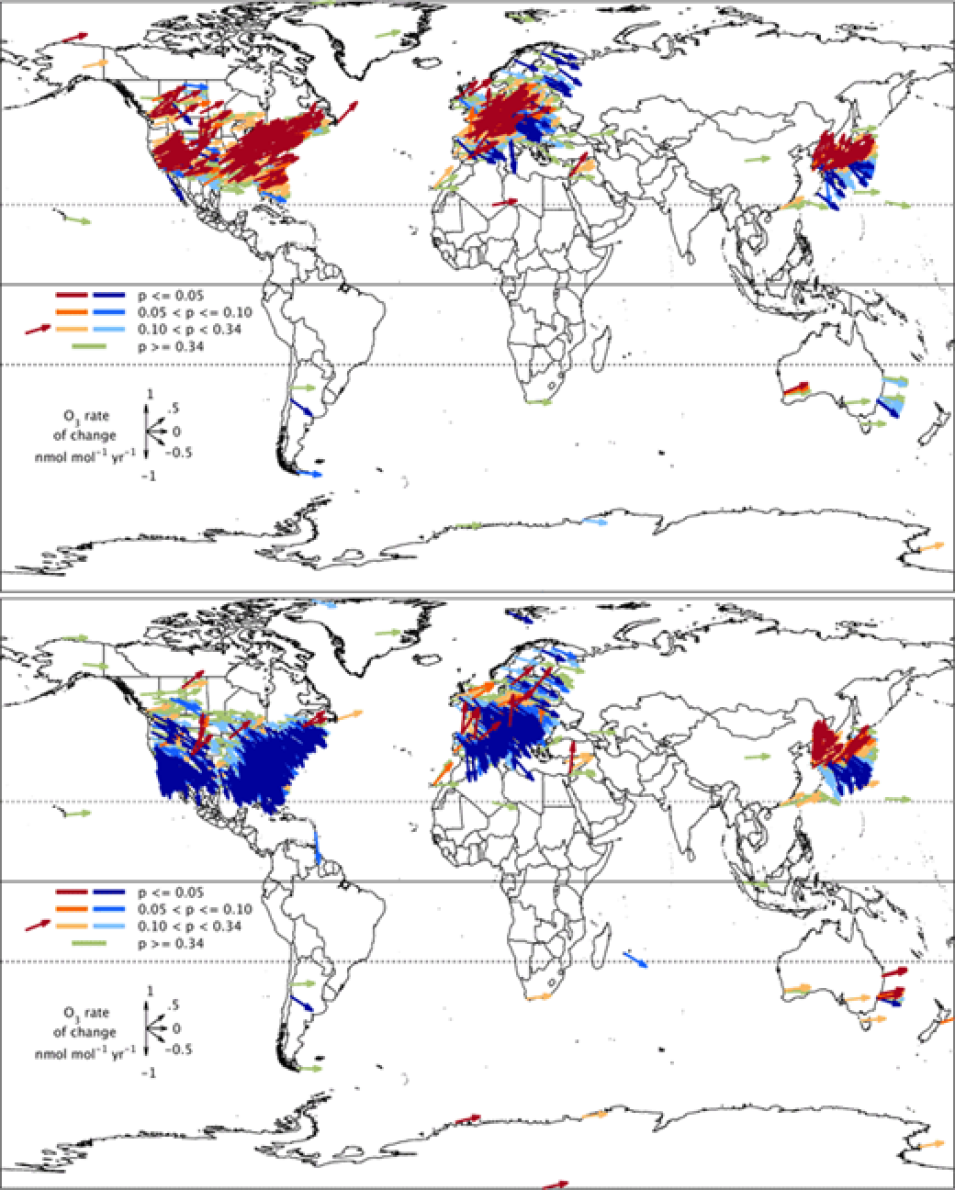

Research Interests: The regional and intercontinental transport of atmospheric trace gases and particulate matter; trends in U.S. and global air quality; the global tropospheric ozone budget; and the stratosphere-troposphere exchange processes.

Research Highlights: Of all the chemical compounds found in Earth’s atmosphere, ozone (O3) is something of a two-edged sword. In the stratosphere (the layer of the atmosphere 10 to 40 kilometers above the surface) ozone acts as a shield to protect life on Earth, including humanity, from the Sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. A weakening of this shield would make humans more susceptible to skin cancer, cataracts, and impaired immune systems. However, in the troposphere (the layer of the atmosphere from the surface up to about 12 kilometers) ozone is a harmful pollutant that can damage lung tissues when inhaled and harm the cell membranes of plants. Further, when it resides at the top of the troposphere, ozone can act as a greenhouse gas by trapping heat in the atmosphere, thereby contributing to global warming.

The natural concentration of ozone at the surface is about 10–20 parts per billion (i.e., 10 molecules of ozone for every billion molecules of air). However, the levels of tropospheric ozone can rise when pollutants such as nitrogen oxide (NOx) gases from vehicle and industrial emissions react in the presence of sunlight. Given ozone’s potential to be a harmful pollutant and greenhouse gas, atmospheric scientists around the globe are keen to monitor its levels in the troposphere.

“It’s generally gone up over the past 150 years or so,” said Dr. Owen Cooper, Senior Research Scientist with the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) at the University of Colorado Boulder and the NOAA Chemical Sciences Laboratory. “Down near the surface, on the local and regional scale, we also want to know if air quality is improving or getting worse. In places like the Eastern United States, due to effective emissions controls, ozone has really come down. But in the developing world and in places like China and India, it’s getting worse as their emissions go up.”

Cooper would know. Since 2014, he’s led the Tropospheric Ozone Assessment Report (TOAR), an international effort initiated by the International Global Atmospheric Chemistry (IGAC) Project to provide the global atmospheric research community with up-to-date scientific assessments of the trends and global distribution of tropospheric ozone from the surface to the tropopause, the atmospheric boundary separating the troposphere from the stratosphere.

“TOAR is an international effort to understand how much ozone is in the troposphere and whether or not it’s increasing or decreasing,” said Cooper. “It’s complicated because ozone is very reactive. It’s not like carbon dioxide, which more or less does the same thing everywhere. Ozone has a short lifetime and is difficult to track. So, it takes efforts from dozens, even hundreds of scientists from around the world to do that.”

The first phase of TOAR ended in 2019, so Cooper and his colleagues are now in the second phase, which will conclude in 2024. At that time, the research team will provide updates on the tropospheric ozone concentrations around the globe, just as it did at the conclusion of phase 1. (Note: TOAR’s reports can be found on the initiative’s website linked above.)