Author Henry David Thoreau wrote about wetlands so often he has been called the patron saint of swamps: “I enter a swamp as a sacred place, a sanctum sanctorum . . . I seemed to have reached a new world, so wild a place . . . ” He found wetlands enchanting, relishing every experience from the sights and sounds to the texture of the mud. Even the scent was enticing, which he described as the fragrance of Earth itself.

Since Thoreau’s time, much has changed, and many wetlands are no longer such wild places. Wetlands are often drained for human development, replaced by steel mills, shipping ports, and homes. This encroachment drives away wildlife and contaminates the remaining water. Some of the greatest damage has occurred around the Great Lakes region, home to one of the largest expanses of coastal wetlands in the United States. Documenting and protecting wetlands has become crucial to the eight states and two Canadian provinces thronging the lakes. While the lakes themselves have been extensively charted, mapping the surrounding wetlands has proven a slippery task.

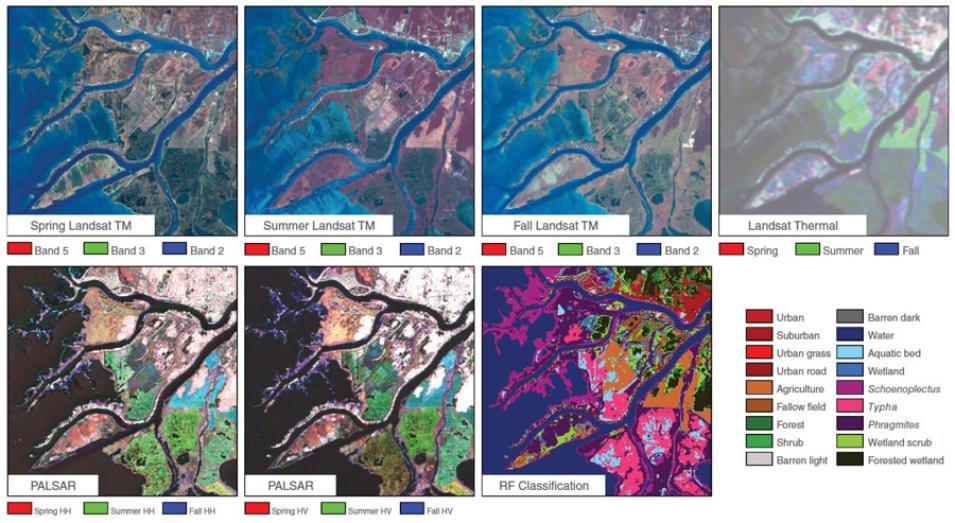

Laura Bourgeau-Chavez, a researcher at Michigan Tech Research Institute (MTRI), was familiar with the problem. She said, “In the past, the United States and Canada have had to patch different maps together.” Bourgeau-Chavez uses satellite data to study land cover, and thought she could develop a way to map Great Lakes wetlands. Armed with satellite imagery, hip waders, and a bit of serendipity, she and her team hoped to produce consistent and accurate maps of the entire basin.