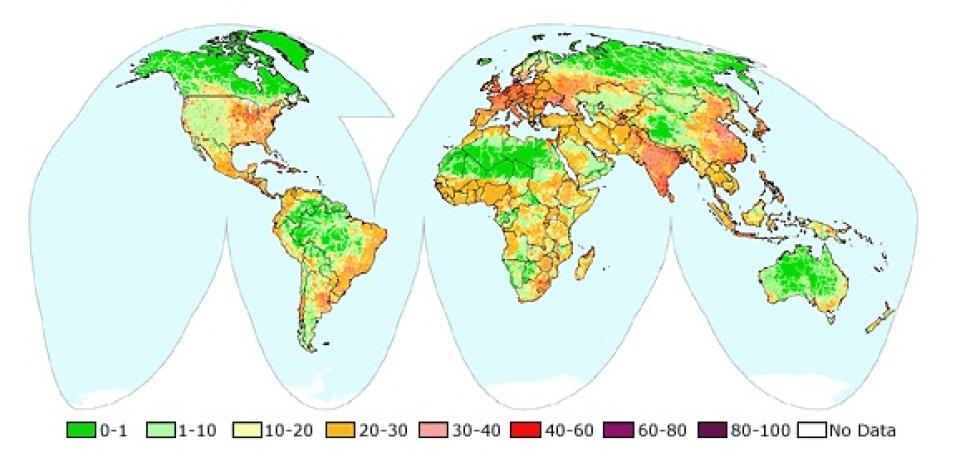

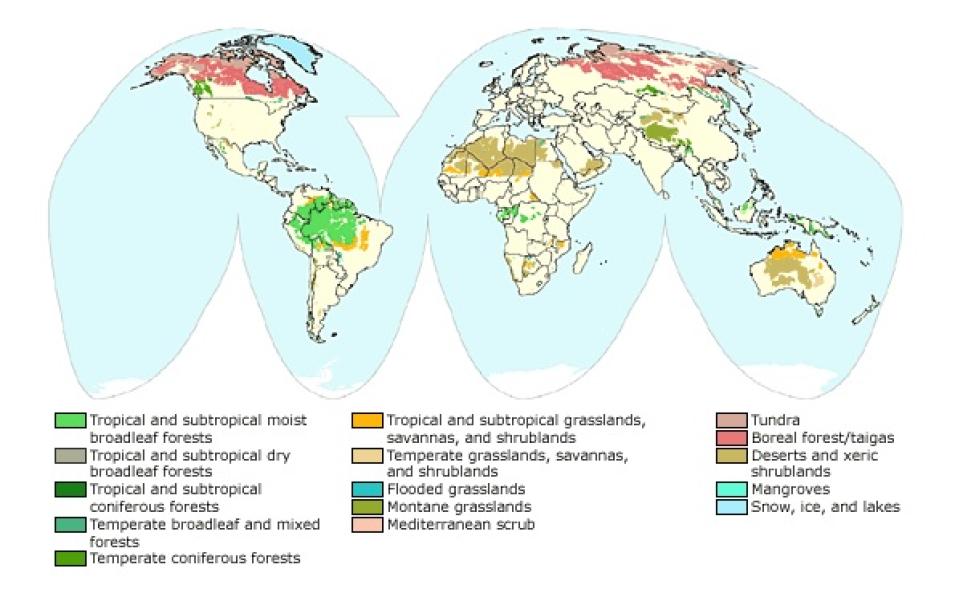

To find the best places to preserve wildlife, the researchers searched the human footprint for the top 10 percent of the wildest areas in each biome. From 568 locations, they selected the 10 largest contiguous areas. While some of those areas cover more than 100,000 square kilometers (38,610 square miles), other biomes have no undisturbed wild areas larger than 5 square kilometers (3.1 square miles). (The Wildlife Conservation Society has made the complete list available through its Web site.)

“It’s important to conserve these remaining wild places, and not solely because of moral or aesthetic values,” said Sanderson. “Preserving places that are already wild is the most practical thing to do. Fewer people, less infrastructure, less human land use, and less power lead to less human conflict.”

A recent article in Science provides another compelling argument for preserving wild places. Andrew Balmford of the University of Cambridge and his co-authors cited the often-overlooked economic benefits of healthy ecosystems. They found that in addition to the harvest of wild organisms for food, fuel, fiber, and medicine, people also benefit from ecosystem services like nutrient cycling, soil formation, and flood protection. Although ecosystem services have not historically been priced, the authors estimated that an effective global conservation program would repay its cost a hundredfold.

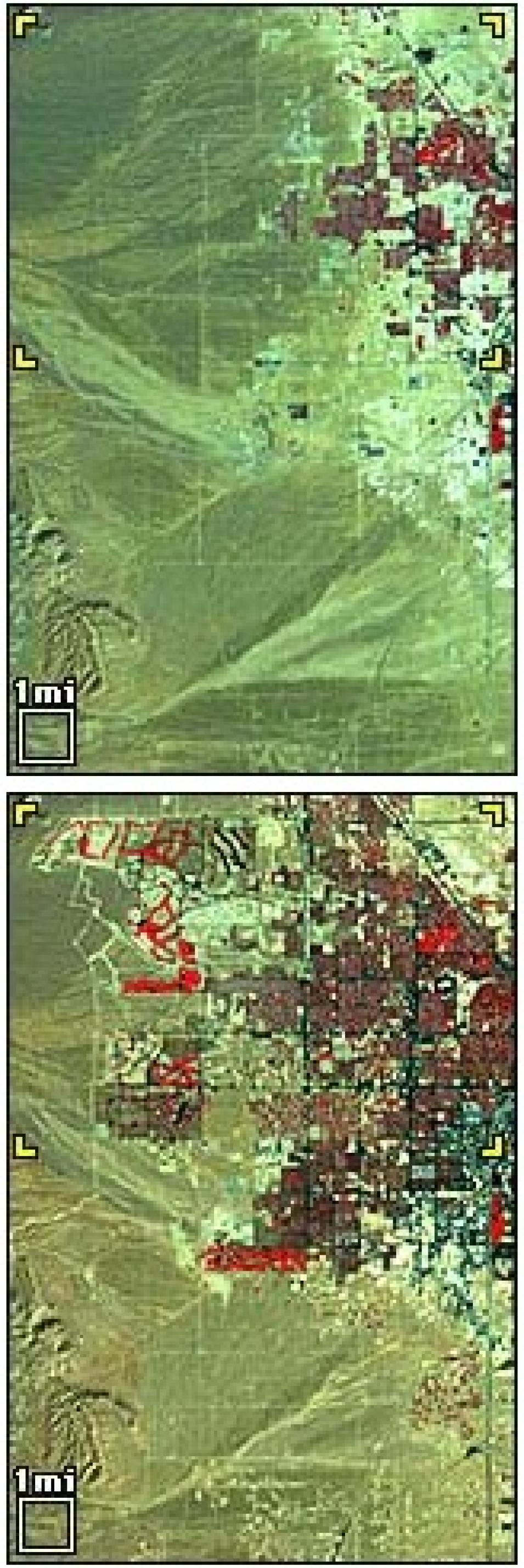

But is human presence necessarily bad? “People convert land cover for a host of reasons, some of which are very necessary and good for human welfare,” said DeFries. “We need to eat, so we have cropland. We need places to live, so we have urbanization. But we also need a way to assess the tradeoff between the obvious benefits and possible negative consequences. Then we’ll be able to make informed decisions to both satisfy human needs and maintain the ecosystem services that vegetation provides.”

“No matter where you are, there’s something in nature that’s worth saving,” said Kent Redford, director of the Wildlife Conservation Society Institute. “If you live in a city, you can build a ‘green’ roof so that migratory butterflies have a place to stop. If you live in a suburban setting, you can develop street curbs that allow turtles and amphibians to cross without getting pulled into the drains. If you’re in a rural setting, you can try to control urban sprawl and the use of pesticides.”

“I think most people feel sad about what’s happening to the natural world, and they want to make better choices,” said Sanderson. “But I also think a lot of people feel helpless about what to do. That’s why conservation organizations exist — to try to offer solutions.”

According to Sanderson, it is especially important to conserve wildlife “across the gradient of human influence” not just in wild places, but also in cities. Luckily, he can point to some success stories. “Hawk migrations over New York City had almost come to an end between the 1920s and 1940s. Now that threats from DDT and recreational hunting have been reduced, the birds are returning, and thousands of people come to the city to see them,” he said. “It’s a magnificent sight. It’s amazing.”

References

Balmford, Andrew, Aaron Bruner, Philip Cooper, Robert Costanza, Stephen Farber, Rhys E. Green, Martin Jenkins, Paul Jefferiss, Valma Jessamy, Joah Madden, Kat Munro, Norman Myers, Shahid Naeem, Jouni Paavola, Matthew Rayment, Sergio Rosendo, Joan Roughgarden, Kate Trumper, and R. Kerry Turner. 2002. Economic reasons for conserving wild nature. Science. 297(5583):950-953. (Registration or subscription may be required for access.)

Sanderson E. W., M. Jaiteh, M. A. Levy, K. H. Redford, A. V. Wannebo, and G. Woolmer. 2002. The human footprint and the last of the wild. Bioscience. 52(10):891-904. (PDF file, 1.7 MB)

For more information

NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC)

The Human Footprint and the Last of the Wild

The Human Footprint from the Wildlife Conservation Society

Last of the Wild from the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN)

| About the data used |

| Data |

Mapping global human impact as well as wilderness areas |

| Parameter |

impact of human activity |

| DAAC |

NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC) |