When a bird develops the feathers needed to fly, it becomes a fledgling and is ready to leave the nest to explore the broader world. For participants in NASA Openscapes who have learned the skills necessary to work with NASA’s open archive of Earth observation data in the cloud, fledging refers to taking their new knowledge back to their organizations and setting up their own cloud-based environment for conducting scientific research.

“Fledging to me is like spreading your wings and soaring off,” says Dr. Julia Stewart Lowndes, the Openscapes founding director. “Fledging is really trying to answer the question of where researchers go after they’ve learned how to use the NASA Earthdata Cloud in our cloud environment designed for training and first experimentation.”

Two Openscapes participants who are fledging are Dr. Aronne Merrelli from the University of Michigan and Dr. Elizabeth (Eli) Holmes from NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). The two researchers and their organizations are benefitting from their work using NASA Openscapes resources (including the NASA Earthdata Cloud Cookbook and the earthaccess Python library) and interacting with mentors and cloud data experts from NASA’s Distributed Active Archive Centers (DAACs). Their fledging experiences provide a glimpse into NASA Openscapes along with the benefits and the challenges of working with NASA and other scientific data in the cloud.

An Open Invitation to Use NASA Earth Science Data

Thousands of data collections can be freely explored and downloaded using NASA Earthdata Search. These data from satellite, airborne, and ground-based observations have a volume of more than 116 petabytes (PB) as of the end of August 2024 and are one of the largest open Earth science data collections on the planet. Moving data to the Earthdata Cloud provides greater efficiencies for using these data collaboratively, working with large data volumes, and analyzing multiple data collections simultaneously. Cloud-based data also can help further open science and efforts to make data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR).

NASA Openscapes is an initiative co-led by Lowndes of Openscapes and Erin Robinson of Metadata Game Changers and is funded by NASA’s Earth Science Data and Information System (ESDIS) Project. Openscapes’ work with NASA began in 2021 as a three-year effort to grow a mentor community of data experts from across the 12 NASA DAACs to create common resources and teaching approaches to support scientific researchers using NASA Earth science data in the cloud.

The first phase of Openscapes is called onboarding. During this phase, NASA Openscapes mentors guide scientists in their first hands-on experience working with cloud-based NASA data in an open-source JupyterHub environment managed by the International Interactive Computing Collaboration (2i2c). Onboarding also includes workshops, hackathons, and learning events such as the Openscapes Champions program.

After the onboarding mentorship phase, scientists move to the fledging phase, where they set up their own cloud environment for scientific investigations and share their lessons-learned with their colleagues and in their organizations. “How do they reuse the computing environments that we developed? How do they think about storage and costs? How do they get funding [for cloud computing]? There are a lot of parts to fledging,” says Lowndes.

Leaving the Nest—Two Fledging Experiences

Dr. Aronne Merrelli, Associate Research Scientist, College of Engineering, University of Michigan

Merrelli describes himself as a “Level 1 and Level 2 algorithm scientist” who works with data from instruments managed by NASA, NOAA, ESA (European Space Agency), and other organizations, primarily in the Python coding ecosystem. He went through the NASA Openscapes Champions program in 2023 and says the cloud enables him to look at new science questions.

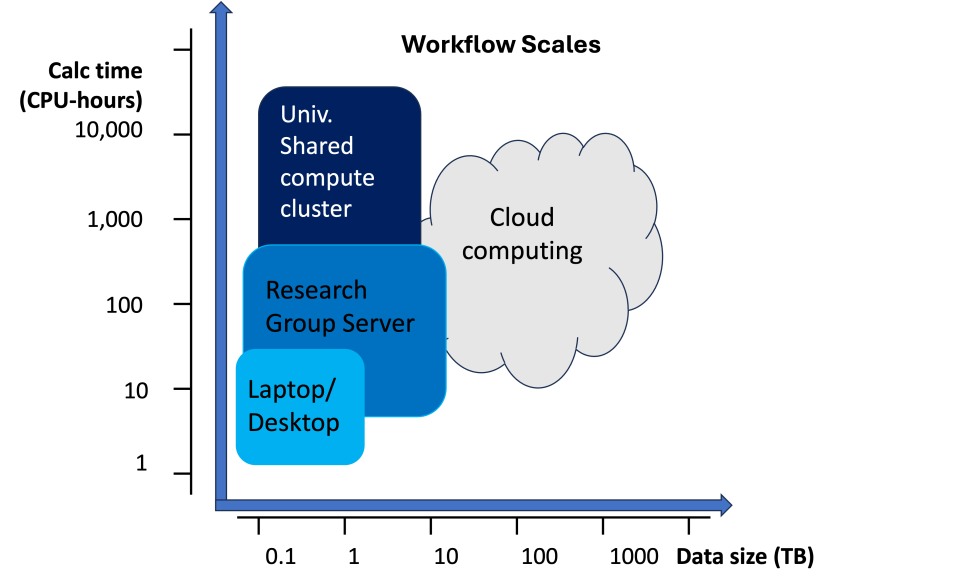

“I see the cloud as a new capability that’s allowing me to do analyses on big datasets that would have been hard to do on [non-cloud-based] machines,” he says. While Merrelli observes that cloud computing likely will not replace any of his existing computing environments (including his personal laptop, a research group server, and a university-based shared computing cluster), the cloud is his destination of choice for processing large datasets.