In the summer of 2014, I spent a day in Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C. I was hiking off-trail, venturing into the woods, and, most importantly, not wearing bug spray. A few days later I felt tired and achy. I thought I had a bad cold or the flu.

Later, while I was swimming in a pool, my boyfriend pointed at my back with a terrified look on his face. “You have a big bull's-eye rash on your left shoulder blade,” he said. Sure enough, the glaring bull's-eye rash on my back told me I had probably been bitten by a tick carrying bacteria known as Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease.

I had only recently moved to D.C. and hadn't realized that I needed to check for ticks. The doctor confirmed that it was Lyme disease and I took a hefty course of antibiotics to clear it from my system.

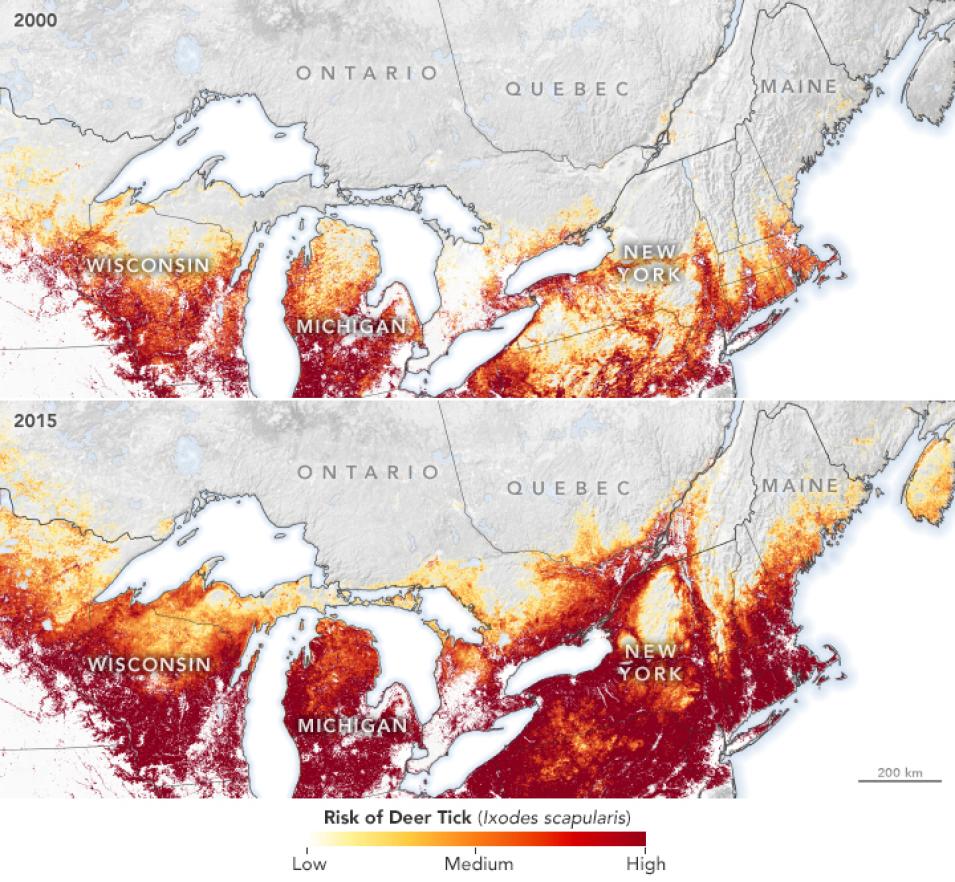

Lyme disease is one of the most common vector-borne diseases in North America. In 2014, my case was one of more than 25,350 reported in the U.S., according to the CDC. Deer ticks (Ixodes scapularis), which carry the bacteria that cause Lyme disease, are found in warm, forested areas in the Northern Hemisphere. And as the global climate warms, deer ticks are migrating north, which means more people are at risk of contracting the disease.

Dr. Serge Olivier Kotchi, who works at the Public Health Agency of Canada, studies Lyme disease as a medical geographer, which means he studies health and disease from a geographic perspective. Specifically, Kotchi has been studying how climate change impacts the incidence of vector-borne diseases in Canada, such as Lyme and West Nile Virus.

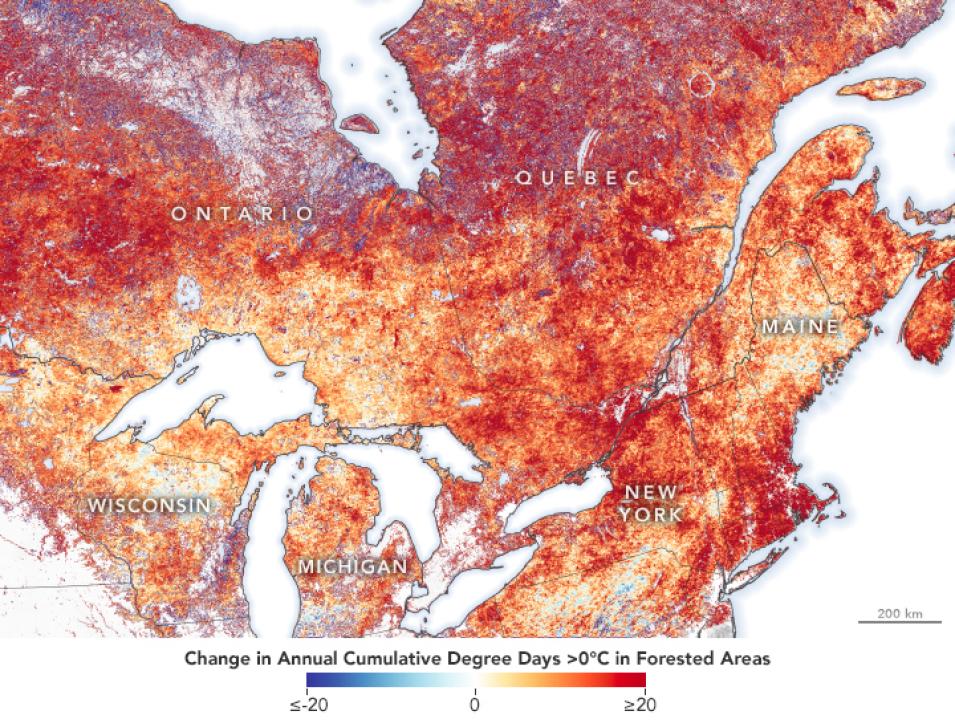

Kotchi and his colleagues recently published a study in Remote Sensing which found that the risk of Lyme disease in Canada is expanding north as temperatures change. They found that between 2000 and 2015, Lyme risk doubled in the province of Quebec in eastern Canada and tripled in the province of Manitoba in central Canada.