High and low

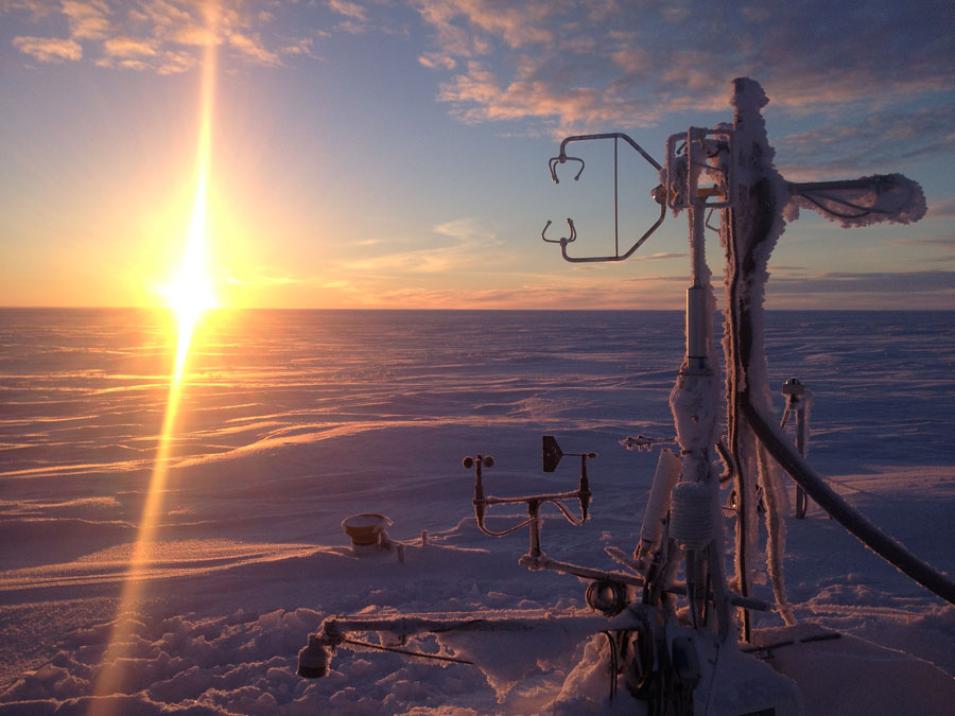

From June 2013 to January 2015, the scientists took turns spending months at the Barrow Environmental Observatory, a cluster of labs at Alaska’s northernmost point and about 1,300 miles south of the North Pole. The observatory lies a few miles from Barrow (population 4,300), which is accessible only by plane. In the evenings, the scientists bunked in sparsely furnished Quonset huts. In the daytime, they watched over five instrument towers equipped with methane-sniffing sensors. Sometimes they had to traverse boardwalks built over the tundra to check on instruments; other times they took planes to get to the towers which are spread out along a 186-mile transect line.

In the summers, the researchers swatted mosquitos and trudged on tundra as mushy as porridge. Summer also brought that singular tundra smell, faintly reminiscent of lavender flowers. In the autumn, winter, and spring, what the researchers consider the cold season, they gingerly walked on tundra alternately soft, crusty, or frozen stiff. The tundra’s top layer, called the active layer, thaws in the summer and freezes in winter, unlike the permafrost underneath that stays frozen all year.

While Zona’s team only saw flat or hilly landscapes with squat vegetation, their colleagues in NASA's Carbon in Arctic Reservoirs Vulnerability Experiment (CARVE) viewed the tundra’s unique features from the sky. On a C-23 Sherpa aircraft, the CARVE researchers gazed at a landscape pockmarked by elongated thaw lakes and polygon shapes patterned by wedges of ice, typical of land underlain by permafrost.

As the tundra cycled twice through summer, fall, winter, and spring, the aircraft flew over the transect fifteen times, measuring methane with a payload of sensors similar to those that Zona’s team tended to on the ground. Was there methane out on the freezing tundra? Could methane-producing microbes even survive the frigid Arctic winter?

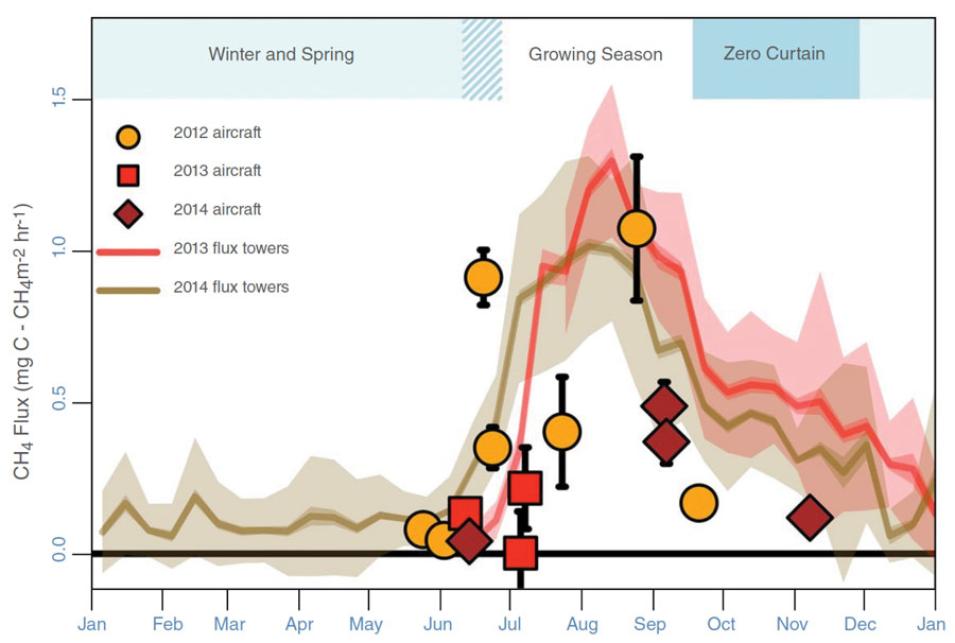

After collecting data for two years, instruments on the ground and in the air agreed: methane emissions during the cold season accounted for more than 50 percent of the total annual methane emissions. This contradicts what computer models assume, that the Arctic’s largest methane emissions come from wetlands, and only happen in the summer.

The findings could call for big changes in the way scientists collect data on methane emissions. “We need to consider the cold period to arrive at an accurate budget of Arctic methane emissions during the entire year,” Zona said. Indeed, methane rises from the tundra in the winter, and the researchers traced it to unexpected stirrings within the active layer.