For the U.S. Navy, which has thousands of personnel aboard ships at sea at any given time and installations in coastal areas around the world, knowing the location of tropical cyclones, the direction in which they’re headed, and whether they are strengthening or waning is critical. So too is monitoring the atmospheric and oceanic conditions that lead to the development of severe storms. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that the Navy has both a meteorological organization—the Naval Meteorology an Oceanography Command (NMOC), which provides worldwide meteorology and oceanography support to U.S. and coalition forces—and a marine meteorology research agency devoted to studying the atmospheric processes that impact fleet operations.

That agency is the Marine Meteorology Division of the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), and among its areas of research is enhancing the prediction and forecasting of tropical cyclones through the assimilation of satellite data from new missions and the development of new data products from existing data streams.

In the following interview, Mindy Surratt, a researcher with the Marine Meteorology Division, and her NRL colleagues, researcher Charles Sampson and meteorologist Chris Camacho, discuss how access to satellite data from a variety of platforms and instruments, collaboration with members of the data-user community, and low-latency observations from NASA’s Land, Atmosphere Near real-time Capability for Earth observations (LANCE) benefit their work.

According to its website, the Marine Meteorology Division conducts basic applied research designed to improve scientific understanding of atmospheric processes that impact fleet operations. Can you elaborate on that? What atmospheric processes are you studying?

Surratt: The NRL facility in Monterey, California, focuses on weather prediction and forecasting—specifically on how weather may affect naval assets. One of the specific things we do is develop guidance to support tropical cyclone forecast efforts, and our main operational partner for that is the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC, a joint Air Force and Navy command) in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. We also work with NOAA’s National and Central Pacific Hurricane Centers. Adding all of their areas of responsibility together, we have global U.S. tropical cyclone forecasting coverage.

Our products are developed specifically to meet JTWC requirements, but they are also heavily used by the two NOAA centers. Clearly, forecasting is very important for the Navy because tropical cyclones and severe storms are going to affect ships at sea and bases in the littoral areas that frequently experience tropical cyclone events.

Given the lack of aircraft reconnaissance in JTWC’s area of responsibility (from the International Dateline to Africa in the Northern Hemisphere and the entire Southern Hemisphere), JTWC relies almost exclusively on a suite of satellite platforms from different countries and agencies that provide global coverage of tropical cyclones, especially in data-void regions. This suite of satellites is a combination of geostationary and polar-orbiting satellites, each of which has its own strengths and weaknesses. For example, even though geostationary sensors provide global coverage at high temporal resolution, their wavelengths are currently unable to provide the same level of detail available from sensors aboard polar orbiters. Microwave imagers, synthetic aperture radar (SAR) instruments, and scatterometers aboard polar orbiting satellites are critical for helping us better understand internal storm structure, low level wind speeds, and ocean surface wind vectors. When taken together, these satellites provide rapid refresh of tropical cyclone detection in these data-void regions.

How do the forecasts generated by the NRL complement or supplement the meteorological information you receive from NOAA and other agencies or entities around the world?

Sampson: In the U.S., we've got an agreement that specifies who does what and where, so [there is] something of a divide and conquer approach to tropical cyclone forecasting. The National Hurricane Center covers the Atlantic, the Central Pacific Hurricane Center covers the Central Pacific, and the JTWC covers the Western Pacific, Indian Ocean, and the entire Southern Hemisphere. When you add them together, you get global coverage for tropical cyclones.

Surratt: We get data from agencies around the world, so we're integrating information from NASA, NOAA, the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Space Force, [and] our partner space agencies in Europe. We're integrating all this information, processing it, and disseminating it to the U.S. hurricane and tropical cyclone centers through the Automated Tropical Cyclone Forecast System (ATCF). We also provide information publicly to other centers around the world through our public-facing tropical cyclone website (TCWeb). We're pulling in information from many different agencies and disseminating it to many different agencies, so it's a very collaborative effort.

How often are tropical cyclone forecasts issued?

Sampson: Tropical cyclone forecasts are issued in six-hour intervals; for the tropical cyclone forecasters, if you can get super low-latency data (e.g., every 15 minutes as opposed to 3 hours), they'll take it. Such timely data could be very important because they're trying to do an analysis right there on the spot and so data that are three hours old is less useful than data from 10 minutes ago.

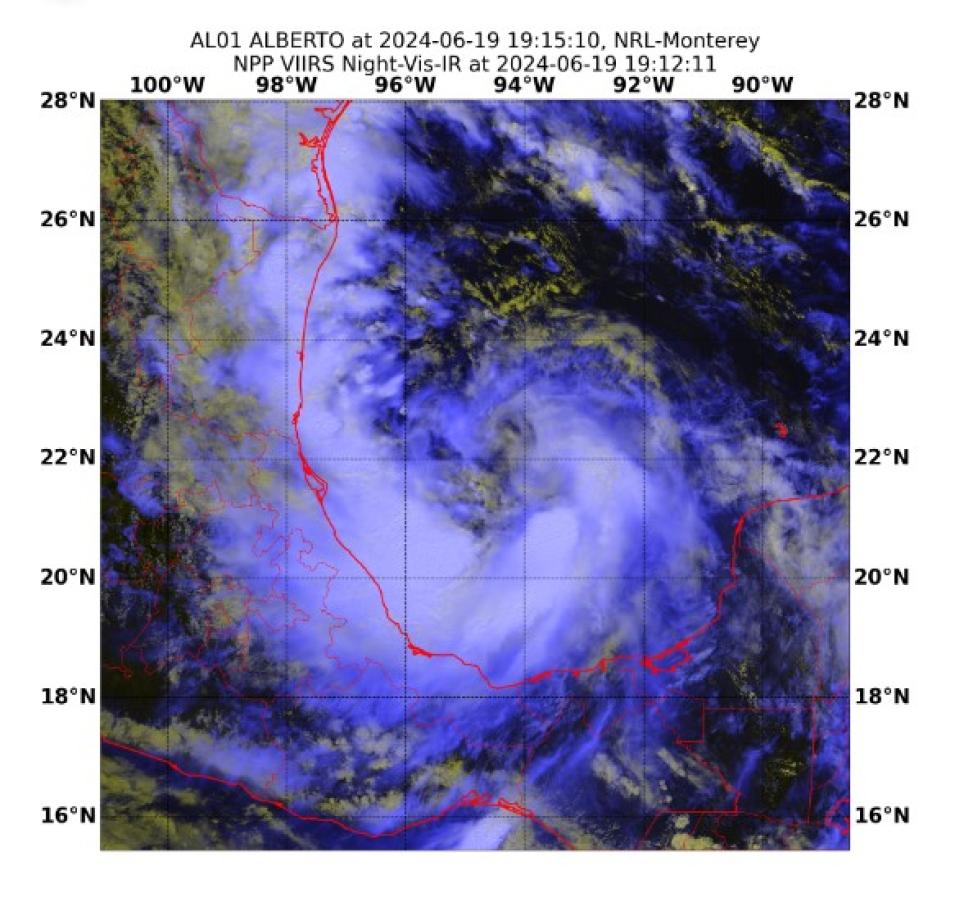

How do NASA Earth science data, particularly the data that you get from NASA’s LANCE, support the NRL’s forecasts? Surratt: One of the most important datasets we get from LANCE for [tropical cyclone] forecasting is from the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite’s (VIIRS) Day/Night Band. It is a critical product that provides consistent imagery both day and night, and it gives a better view of storm structure at night than is currently available from other sources.