Time-Critical Detections

The longer answer has to do with the satellites that detect the fire, their speed in imaging terrain, and the resolution of their instruments.

The Palisades fire was first detected by NOAA’s GOES-16 and 18 weather satellites hovering over the United States in geostationary orbit. The satellites stand watch from orbit capturing images of the U.S. every 10 minutes with its Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI), allowing them to see a fire very soon after it starts.

“Geostationary data, such as from GOES, is often used as a first, initial source for identifying fires because of its immediate availability,” said Jenny Hewson, the outreach and implementation manager for LANCE.

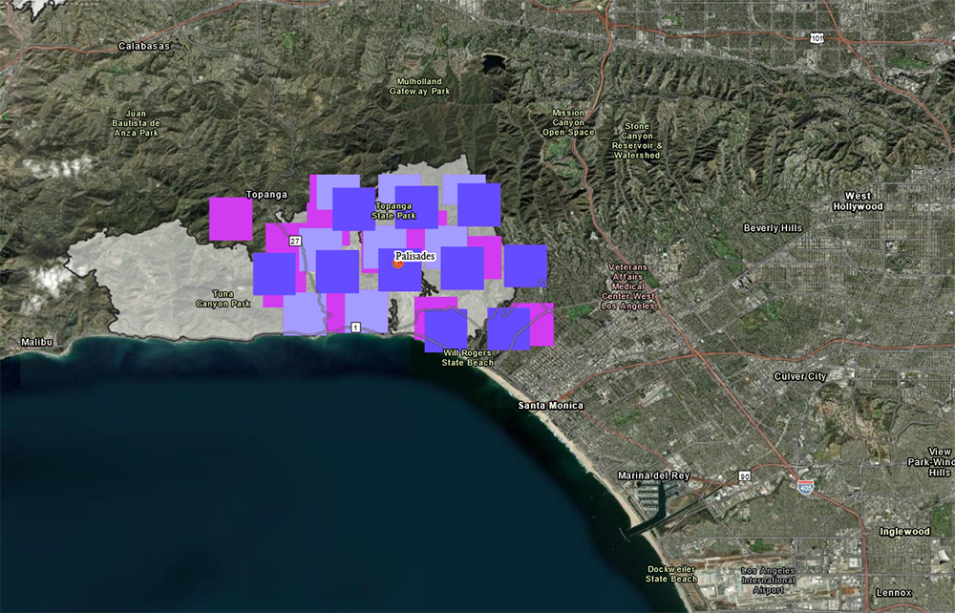

That said, imaging land still takes precious time in these sorts of emergencies—and doing it in fine detail takes even longer. Once a fire starts, time is critical. Because the GOES satellites provide continuous observations, their spatial resolution is a relatively coarse 2 kilometers (km) per pixel when looking directly below the satellite, which limits the level of detail they can show. To visualize the effect of this, imagine an image of the Pacific Palisades area being divided into a grid of 2 km squares. Each pixel in the ABI instrument corresponds with one of those squares. Anything seen in the pixels corresponding to those squares smaller than 2 km in size will be too blurry to be clearly seen, making it difficult to identify and measure the exact dimensions and position of a fire.

To make finding and roughly locating fires a lot easier, they’re spotted in the imagery using fire-detecting computing algorithms that scan each pixel for the sometimes subtle kind of light, heat, and other signals of a fire. If fire is suspected within the pixel’s 2 km coverage, the pixel square is flagged and a 2 km-wide colored block labeled as fire is added to the map. So, there could be just a small, intense spot fire located anywhere within that pixel, but if it’s bright and visible enough to be seen from space, the entire 2 km area on the map is labeled as a suspected fire. Again, this is because we can’t be sure of the exact location of anything smaller than 2 km due to the satellite’s resolution.

If the same small fire is found in an area bordering multiple pixels, all of the pixels will be labeled. For example, a small fire in an area bordering where four square pixels meet could be flagged as four pixels large or 4x4 km in size. Yes, the area flagged could be larger than the actual fire, but it’s safer to over- rather than underestimate the size of fire when first responding to it. And what if a fire is 2 km or larger? It will be flagged with the number of squares large enough to encompass it and approximate its location.