During the winter of 2016 to 2017, storm after storm blasted Idaho, piling the state’s snowpack far above average. Areas that received more than twice the usual amount of snowfall buried plants and bushes, starving wildlife. Only 30 percent of Idaho’s mule deer fawns survived, about half the usual number. Across the western United States, brutal winters like this kill vulnerable does and fawns, decreasing the following year’s population. Even worse, these drops exacerbate an ongoing decline in mule deer numbers.

This decline is troubling, because mule deer are critical to many of the West’s biomes. “Mule deer are an indicator of healthy, functioning wild ecosystems,” said Mark Hebblewhite, a wildlife biologist at the University of Montana. Traditionally, biologists monitor mule deer by capturing a small number of the animals every year and fitting them with radio collars that track them, sometimes until death. However, that method is expensive and time consuming. Hebblewhite and Mark Hurley, a colleague at the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, wanted to find an easier way.

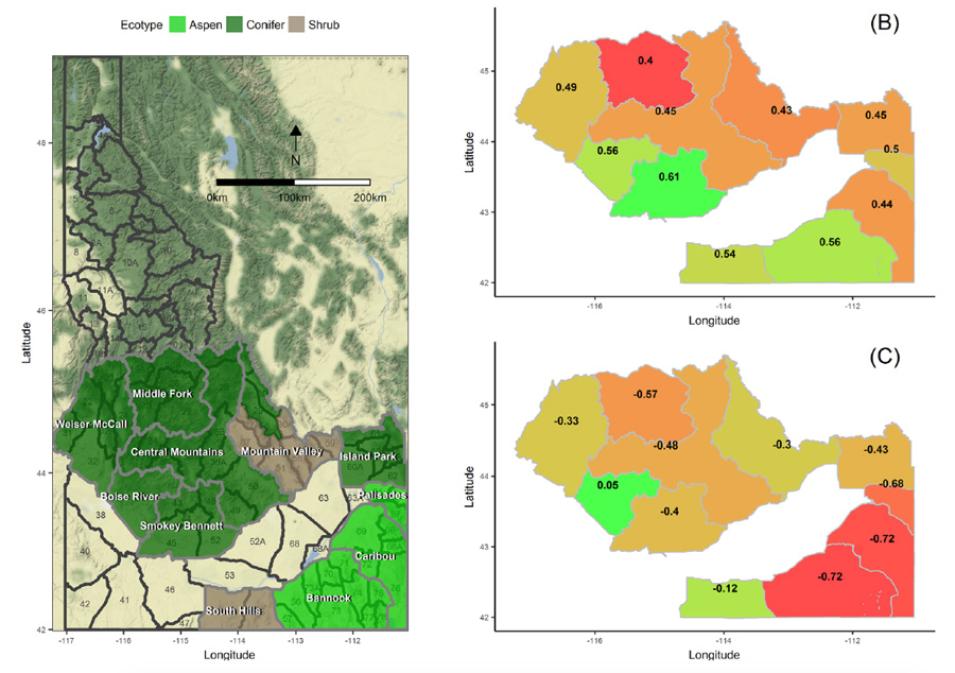

Biologists in Idaho have been radio collaring and monitoring mule deer for nearly twenty years, and the resulting data suggested fawn survival was key to maintaining mule deer populations. Yet fawn survival remained highly unpredictable. What if the researchers could instead track predictors within the ecosystems themselves? “We started looking for ways of measuring habitat- and weather-derived influences on mule deer in different parts of Idaho,” Hebblewhite said, hoping to glean environmental predictors from satellite data. Could distant satellites help them estimate the survival of thousands of tiny fawns?