The snowy reaches of Siberia sprawl across northern Russia, spanning three-quarters of the country. Dense forests of coniferous trees rise from the cold and swampy terrain of sub-Arctic taiga. Further north, the towering woodlands give way to Arctic tundra: frigid open country encrusted with moss and lichen. Dominated by these two biomes, Siberia remained sparsely populated for centuries. By the 20th century, however, rich reserves of oil and minerals were discovered, and Russians eagerly streamed north to fill jobs. The flood of people and industry changed Siberia’s fate, turning quiet settlements first into boomtowns, then into bustling cities.

When oil was discovered in northern West Siberia, Russia wasted no time developing the new oil fields. The small fishing settlement of Surgut was one of the remote outposts dotting the region. Located on the banks of the Ob River, Surgut’s population surged, and it was granted town status in 1965. By 2015 Surgut had become the unofficial oil capital of the country, home to 340,000 people. Modern Surgut now offers theaters and shopping malls, tree-lined streets and parks. And like Russia’s other booming cities, Surgut leaves a growing footprint on its environment.

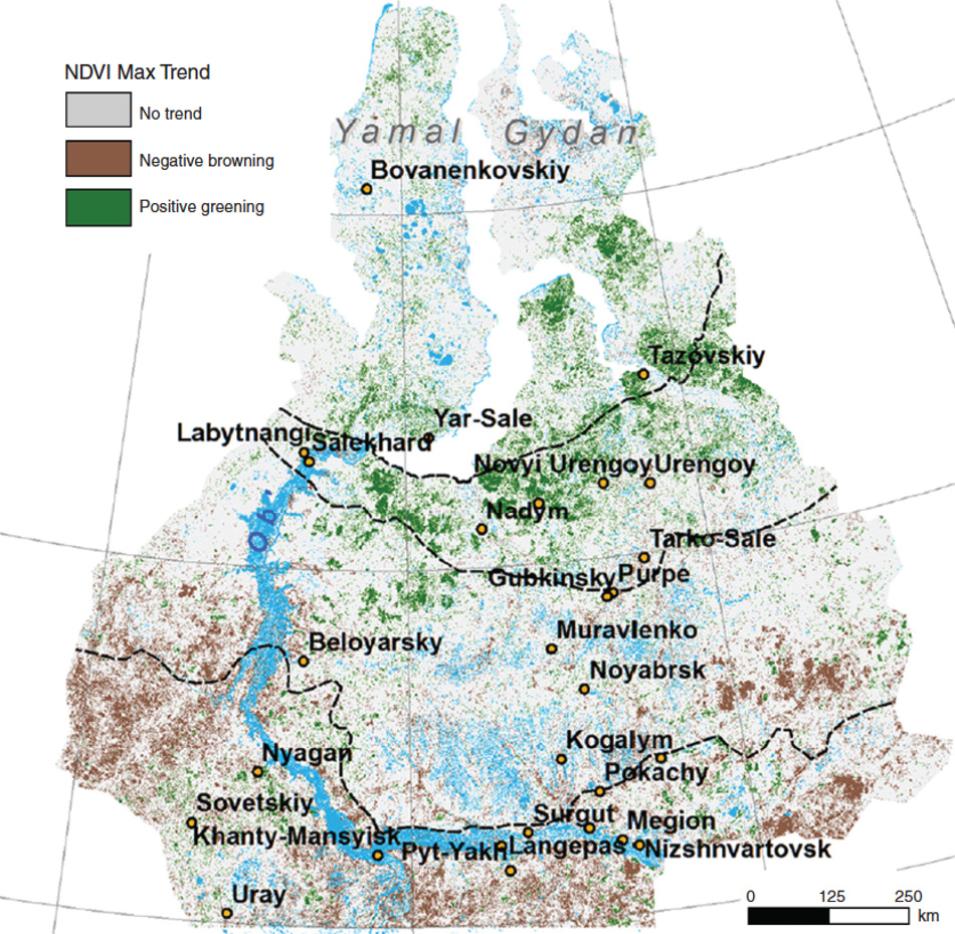

Igor Esau and Victoria Miles, researchers at the Nansen Environmental and Remote Sensing Center in Norway, saw the oil and gas boom as an opportunity to study these footprints. They and their colleagues looked at 28 cities and towns across northern West Siberia as well as at the surrounding natural landscapes. How did urban development affect Arctic vegetation over time? And how might accelerated Arctic warming amplify these changes?