From space, a kaleidoscope of aquamarine and green can be seen swirling around Earth’s oceans each spring. Algae glide near the water’s surface, soaking up sunlight and reflecting green-blue hues back to satellites. Their color reveals patterns of ocean currents and marks the abundant sea life that feed on them, from toothpick-size krill to whales weighing many tons.

Scientists are anticipating changes, though. Algae rely on phenomena called deep water masses to mix the ocean and dredge up nutrients from the seafloor, in effect seeding the water so they can bloom in spring. Yet warmer wind and ocean temperatures could weaken these currents. Pierre-Amaël Auger, a researcher at the Instituto Milenio de Oceanografía, said, “If there’s no wind and no mixing to bring nutrients to the top, there’s no fish.”

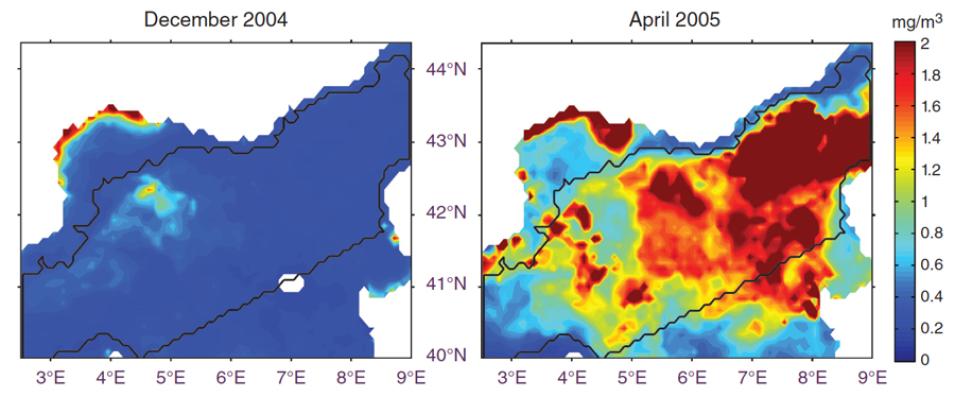

Researchers like Auger have eyed chlorophyll, the bright green pigment that gives algae their color, in satellite images since the late 1970s as a way to study ocean mixing. What has been missing was a longer case study on deep water masses. How they form is not completely understood. Marine Herrmann, Auger’s colleague and a researcher at Laboratoire d’Etudes en Géophysique et Océanographie Spatiales, said, “If you want to understand how they work, you need to understand how they vary.” So they took a closer look at the Mediterranean Sea, an area where deep water masses regularly form and feed algae.