Yellowstone National Park puts on a thrilling show. Geysers steam and spout, steam vents hiss, mudpots spew, and hot springs color their waters with intense yellows, blues, oranges, and greens. Visitors soon learn they are standing on a volcano that has not erupted for about 70,000 years, but still could.

Preventing volcanoes from erupting is beyond human control, but scientists can monitor for the signs of a coming eruption. Changes in heat may be one of those signs. “Yellowstone is one of the places where Earth is letting out a lot of its internal heat,” said Greg Vaughan, a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) researcher who has studied Yellowstone. All of this hot action on the surface can be read as a report on the restless lava and pressures far below ground.

An eye to the surface

People like to talk about the potential for a massive eruption at Yellowstone, wiping out the park and large areas of the three states it straddles, but scientists say that is unlikely. “There have been some very big eruptions there in the past, but many more that were not as big. If there were ever to be another eruption in Yellowstone, it is more likely to be one of those not-so-super eruptions,” Vaughan said.

Yellowstone, like some other active volcanoes, is monitored by a group of scientists who watch for signals that precede eruptions. They use ground instruments to monitor Yellowstone’s 1,000 to 3,000 annual earthquakes, and both ground and satellite observations to spot bulges or subsidence on the surface that indicate magma or hot fluids moving underground, like gophers burrowing under your lawn.

Thermal features like Old Faithful’s clockwork eruptions also hint of the hot magma that causes groundwater to spout boiling plumes into the air. Yet most of Yellowstone’s thermal features are less consistent or stable than Old Faithful. “The National Park Service (NPS) monitors these features and how they change,” Vaughan said. “They disappear and move around. New ones pop up where they have never been before. The NPS needs to understand how this ever-changing thermal activity affects visitor safety, and park infrastructure—for example, if they are going to build a new road.”

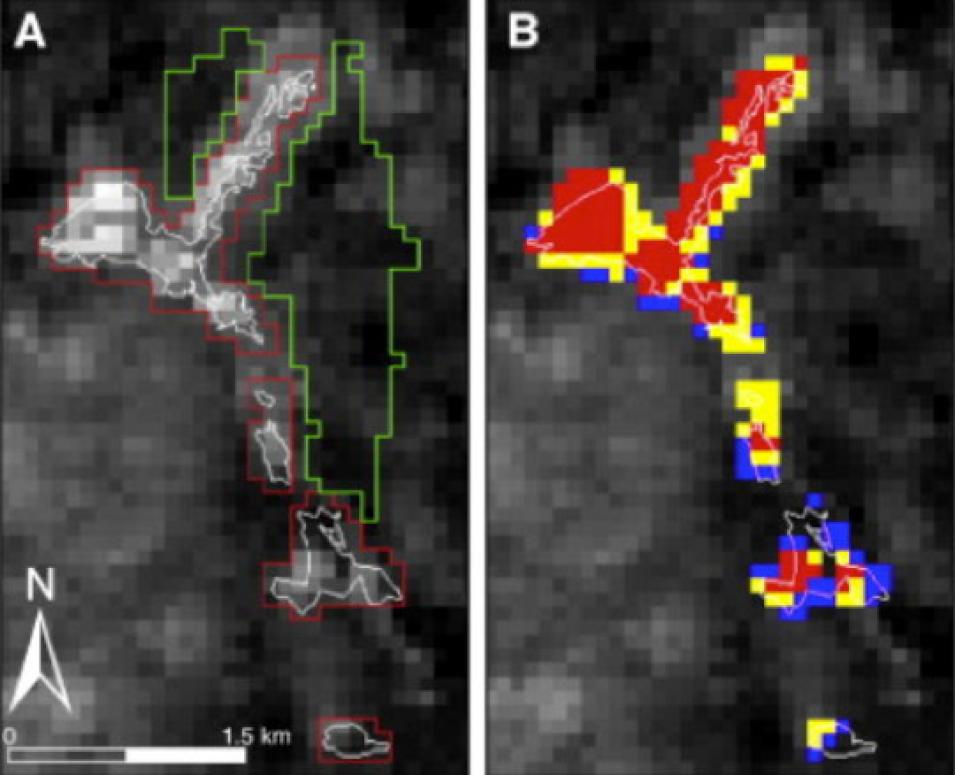

Vaughan is interested in what changes in thermal activity can say about volcanoes. “Thermal anomalies often precede eruptions, but it is usually after the fact that we realize this,” he said. While the park has placed sensors at some locations, it is impossible to monitor on foot Yellowstone’s more than 10,000 geothermal features spread over 3,472 square miles. Most volcanoes in the world are not monitored, nor do they sit within a popular park. They may have limited or no instrument networks to alert scientists of their growing wrath. “For a lot of volcanoes, a satellite image might be the first indication of an eruption,” Vaughan said.