Another key factor in ocean circulation is salt. Salt water is denser than fresh water, and therefore sinks. Cold water is denser than warm water, and likewise sinks. Consequently, fresh, warm water remains near the surface and salty, cold water sinks into the deep ocean. This produces the continual churning and movement that form a large set of the world’s ocean currents, called the Meridional Overturning Circulation.

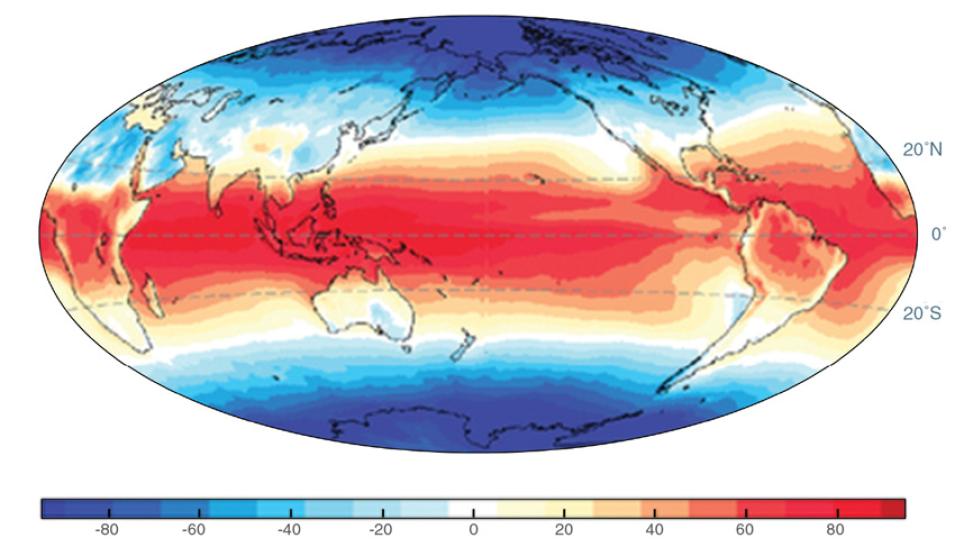

Frierson and his colleagues focused on a giant, continuous loop in the Atlantic that transports warm water from the tropics to the poles, traveling all the way from Antarctica to Greenland. At the poles, sea ice squeezes salt out of water as it freezes, leaving even saltier water. “Salty and cold water sinks in North Atlantic high latitudes. The dense water travels in the deep ocean and most of it upwells in the Southern Ocean,” Hwang said. “The overturning circulation in Atlantic constantly brings warmer water from Southern Hemisphere to the Northern Hemisphere and brings colder, denser water away from the Northern Hemisphere.”

While landmasses may not directly contribute to hemispheric warming, they do affect ocean circulation. Hwang said, “The way that the continents are set up makes the Atlantic saltier than the Pacific, which is a key driver of the Meridional Overturning Circulation.”

When the researchers modeled ocean heating, they confirmed that temperature overturning was creating a warmer North Atlantic. “Water sinks near Greenland because it’s really cold and salty,” Frierson said. But they also found this warming helped drag the rain bands slightly north of the equator. “The sinking cold water near Greenland just flushes out all the really cold stuff from the North Atlantic,” Frierson said. “So you’re left with warmer water there, and it sort of tugs all the warmth toward that, too.” The ocean releases some of that heat into the atmosphere, which in turn fuels atmospheric heat circulation and pulls more warm air to the north of the equator. That pool of warmer air creates the tug, shifting tropical precipitation slightly north.

Tail wagging the dog

Scientists long thought that the tropics control global climate and weather patterns. But they have since realized that extratropical regions, further from the equator, also influence far-reaching patterns. “We’ve discovered in the last ten years or so that even the high latitudes have big impact on tropical rainfall,” said Frierson. “It was kind of like the tail wagging the dog.” This means that changes in polar climate or sea ice formation could influence where rain falls. “The Meridional Overturning Circulation is very slow—it takes hundreds of years to recirculate,” he said. “But it is something that we expect to change with global warming.”