Early one April morning, a Yucatán farmer stooped over the stubble of his sugar cane field to set it on fire. Torching it would make a bed of rich ash for new seedlings. The smell of burning plant matter stung his nose as a great plume of smoke and soot rose up in the wind.

Just a few days later, a massive tornado tracked across Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Along with smoke particles, the wind carried all manner of debris: roofs and siding stripped from houses, uprooted trees, even SUVs and boats. A curtain of falling debris stretched across the sky for over 20 miles. A total of 122 tornadoes spun through the southeastern United States on April 27, 2011, killing 313 people, one of the deadliest outbreaks in U.S. history.

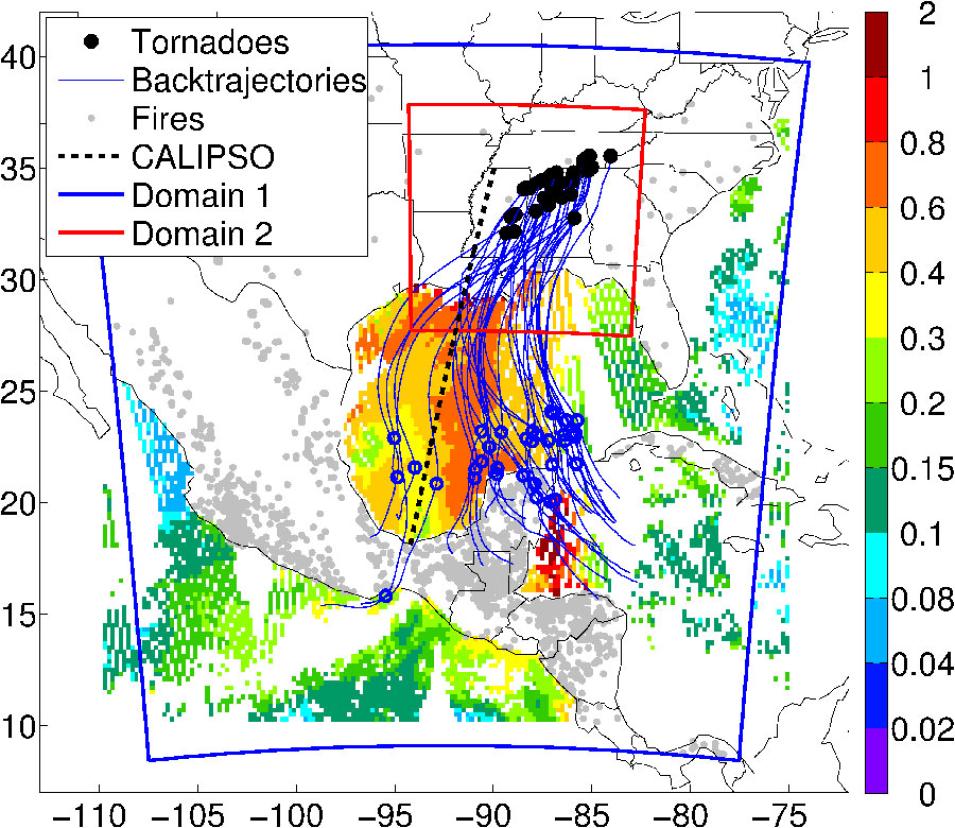

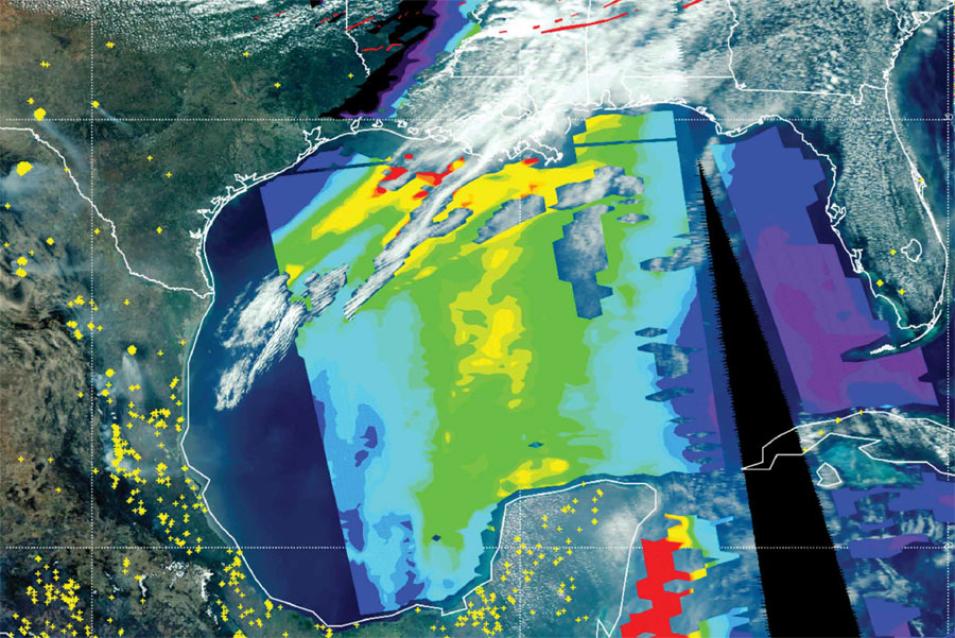

Were these two events connected? At the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Colorado, researcher Pablo Saide squinted at satellite images taken that week in April 2011. He spotted the giant smoke plume heading from the Yucatán towards the United States. Like other scientists, he had suspected a connection between yearly field-clearing fires in the Yucatán and South America, and severe tornadoes in the southeastern United States. If he could show how they were connected, information on smoke could be added to severe weather forecasts to help save lives.