In the summer of 2008, humanity’s fastest, strongest, and most skilled athletes will compete in the Olympic Games in Beijing, China. How will a city that many people associate with traffic-stopping road congestion and health endangering levels of pollution handle the additional influx of Olympians and their many followers?

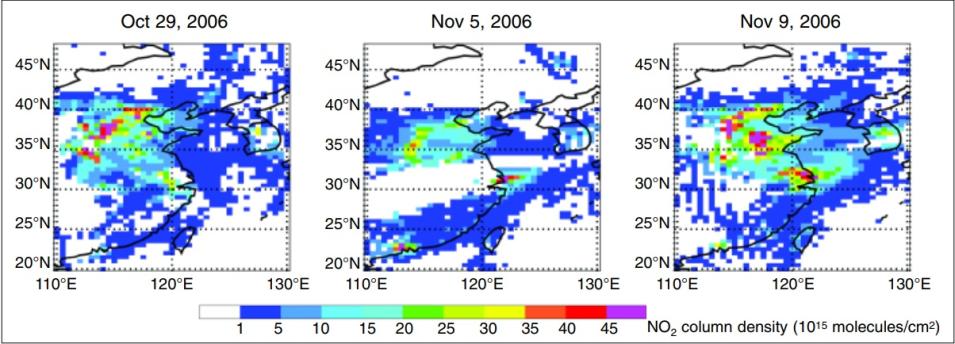

In November of 2006, Chinese officials used a smaller-scale gathering, the Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, as a sort of dress rehearsal for the Olympics. During six days surrounding the summit, officials increased bus capacity, limited access to certain roads, and banned or restricted the use of government, commercial, and private vehicles. The idea was to make it easier for summit participants to get around Beijing, while also providing a logistical trial run that would benefit athletes and spectators in 2008.

Harvard environmental studies professor Michael McElroy, a participant in a lesser known conference, the China International Counsel for Cooperation on Environment and Development, also happened to be in Beijing in November 2006. McElroy leads Harvard’s China Project, an interdisciplinary program that studies the impact of air pollution on the environment, economy, public health, and law. One morning during his visit, he picked up the China Daily newspaper and noticed an article about the traffic restrictions. He said, “I read the article and thought, ‘Aha! Wouldn’t it be neat if we could take advantage of this natural experiment to improve our ability to detect pollution and see if the restrictions had an impact?’”