Day-in and day-out, for the past 20 years, NASA’s Aqua satellite—one of three flagship satellites in NASA’s Earth Observing System (EOS)—has dutifully maintained a sun synchronous polar orbit 705 kilometers (km) above the Earth, crossing the equator at a mean local time of approximately 1:30 pm. In fact, as of mid-day on May 4, 2022, the 20-year anniversary of the satellite’s launch, Aqua had completed 106,385 orbits of the earth.

These are noteworthy achievements, for when it comes to Earth observation data from satellites, consistency is key. Establishing a credible data record to detect changes in the Earth system over time requires satellites and satellite instruments that are reliable and stable. Aqua has not only met these requirements, it has exceeded them. The satellite has functioned largely without interruption in the harsh environment of space since it launched into orbit on May 4, 2002, and as evidenced by its two-decades-long data record, its instruments have observed the planet in the same way, from the same position almost every day since the satellite was declared operational in July of that same year.

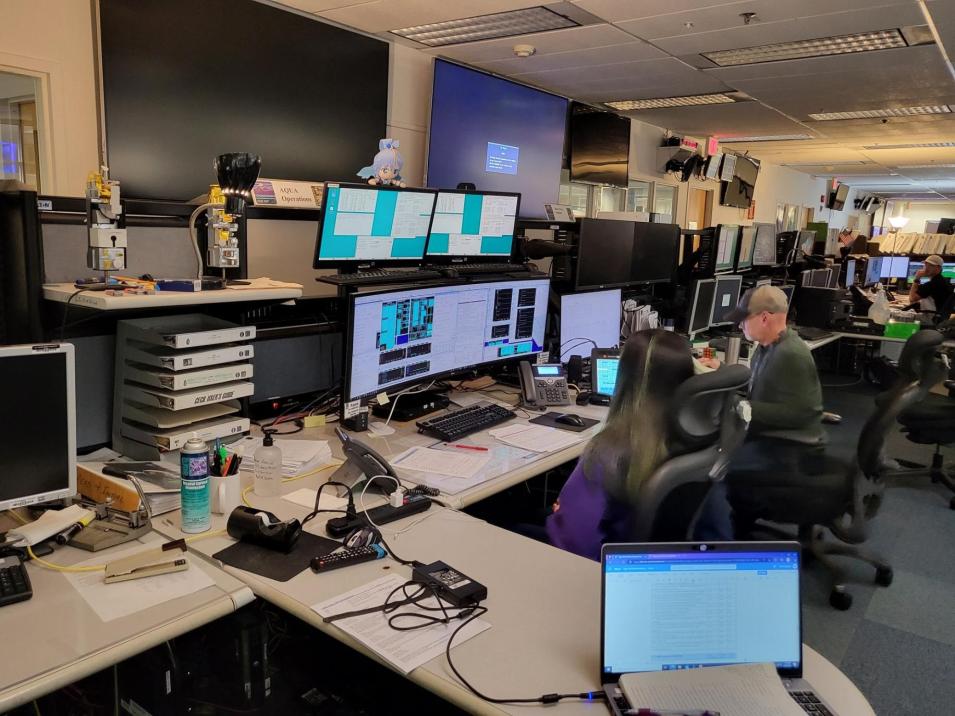

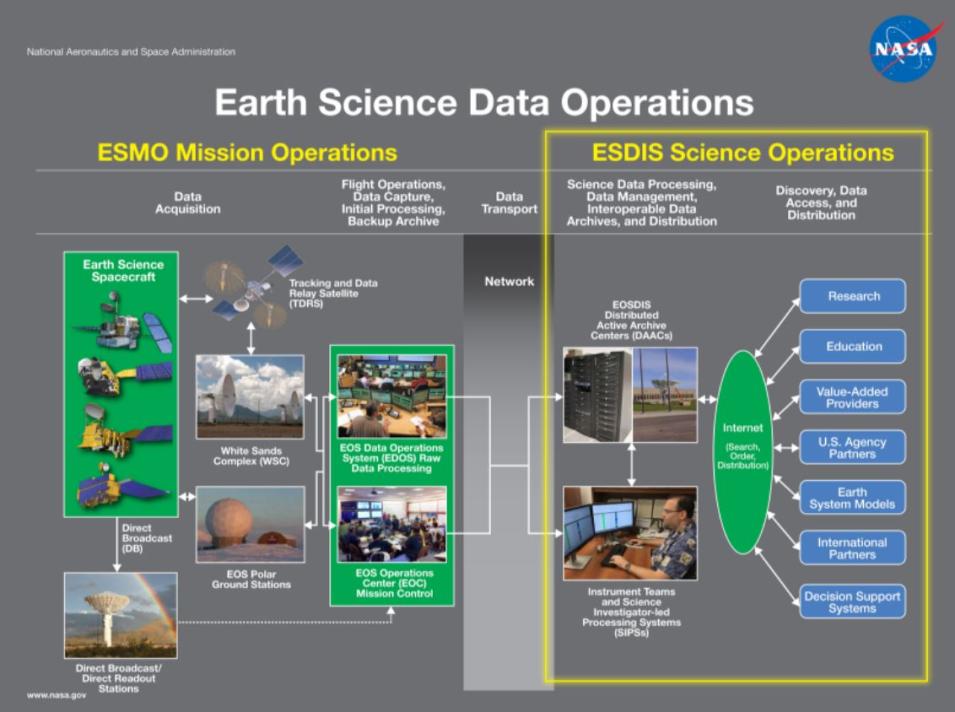

Credit for Aqua’s remarkable longevity in space is readily given to the engineers who built the spacecraft and its instruments and to NASA’s Earth Science Mission Operations (ESMO) Project at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, located in Greenbelt, Maryland. ESMO is responsible for the operation and maintenance of Aqua and other EOS spacecraft along with other Earth science missions conducted by NASA’s Earth Science Projects Division (ESPD).

Yet, according to Aqua Mission Director Bill Guit, the way ESMO conducts its operations is unique to the attributes of each spacecraft and the goals of each mission.

“Operations is driven by how frequently you have to communicate with the spacecraft,” said Guit. “[On Aqua] we’re driven by the size of our on-board solid-state recorder (SSR). It can only hold about two-and-a-half orbits-worth of data, so, consequently, we have to dump those data to the ground every orbit.”

There is also a data-latency requirement with the mission such that data from Aqua’s instruments must be distributed to the National Weather Service within a matter of hours from download.

“Getting yesterday’s data is no good for tomorrow’s forecast,” Guit quipped.

Although ESMO contacts the satellite every orbit—and Aqua orbits the Earth every 99 minutes (approximately)—much of the interactions are pre-arranged with a standing schedule that’s made weeks in advance.