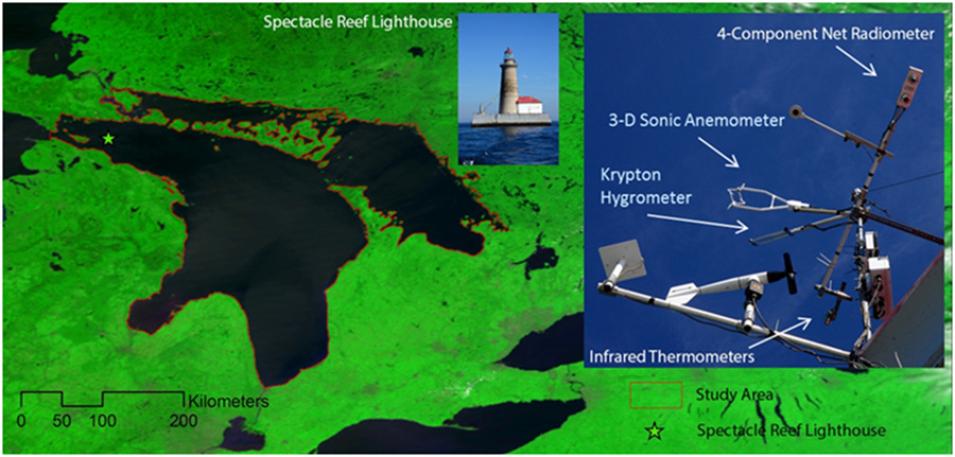

Shortly after the boat set out onto Lake Huron, dense fog swelled. Unable to see beyond the bow, radar guided the researchers to Spectacle Reef Light, a lighthouse, 11 miles offshore. “We literally almost hit our heads on it,” said Peter Blanken, a researcher from the University of Colorado Boulder. The team was checking on the instruments on top of the lighthouse, which was being used as a key research site.

The Great Lakes contain 20 percent of the world’s surface fresh water and provide 35 million people with drinking water. “Surprisingly we know very little about them,” Blanken said. “They’re very poorly studied.” Their immense size has led many to perceive them as unresponsive to climate change. From 1998 to 2014, water levels dropped in the Great Lakes to the longest low-level period in over 100 years. Then in 2016, water levels recovered in Lake Huron, jumping more than three feet after 12 days of rain.

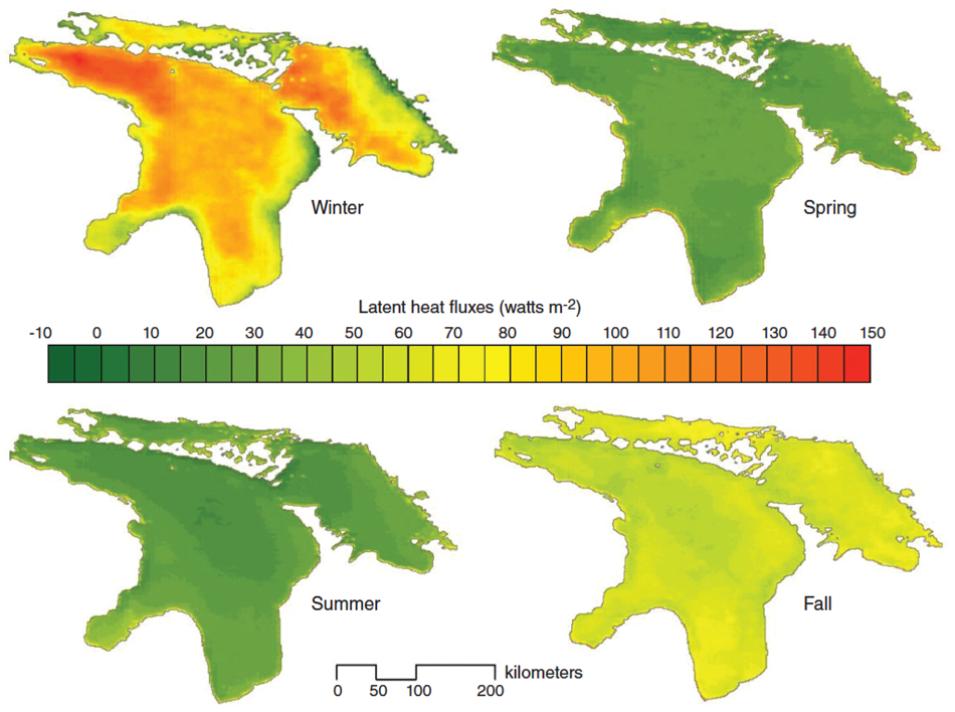

Precipitation is one driver of year-to-year fluctuations, but Blanken suspected another cause. After observing evaporation in the Great Slave Lake, an extensive lake in northern Canada, Blanken had a hunch evaporation may also play a major role in the Great Lakes’ water cycle. Understanding how evaporation works and what it contributes to lake-level changes would provide insight on where lake levels are headed in the long term.