French plant ecologist Andre Aubreville popularized the term desertification in a 1949 paper. He wrote that the desert “is always present in the embryonic state during the dry and hot season.” Sufficient human pressure, Aubreville observed, can transform tropical rainforest into savanna, and savanna into desert. Desertification now threatens more than a billion people worldwide, although its impacts are most severe in Africa. A major impediment to food production, degraded land means roughly $42 billion each year in lost income. Outside the immediately affected areas, it can cause flooding, reduce water quality, create dust storms, and increase incidences of respiratory illness and eye infection.

“But as serious as desertification is, it’s only part of the problem. The phenomenon we’re concerned with is actually bigger,” said Dr. Hank Shugart of the Department of Environmental Sciences at the University of Virginia. “We’re interested in land systems that can change from something desirable to something undesirable, then stay that way.”

Africa’s fragile ecosystems make the continent especially vulnerable to unwanted environmental changes. Shugart compared Africa to parts of the United States and Europe. “In a place with rich soil, if you change the ecosystem and you don’t like the result, you can stop, and the system will more or less restore itself. In parts of Africa and Australia, if you change the land and start seeing results you don’t like, you might get to look at them for a long time.”

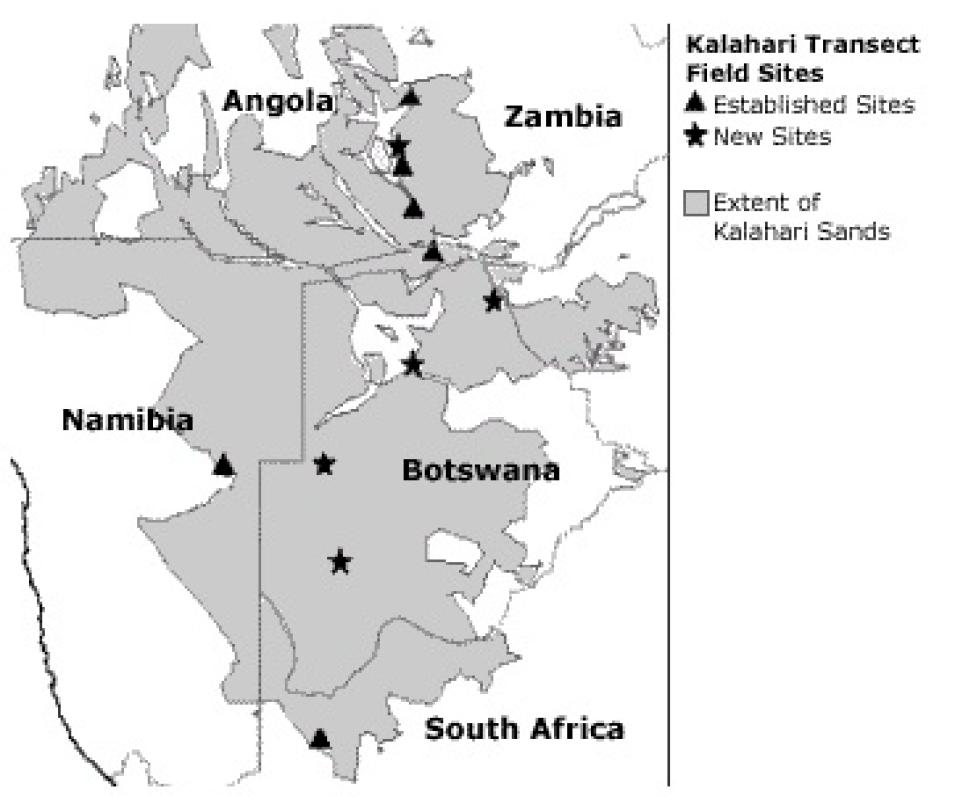

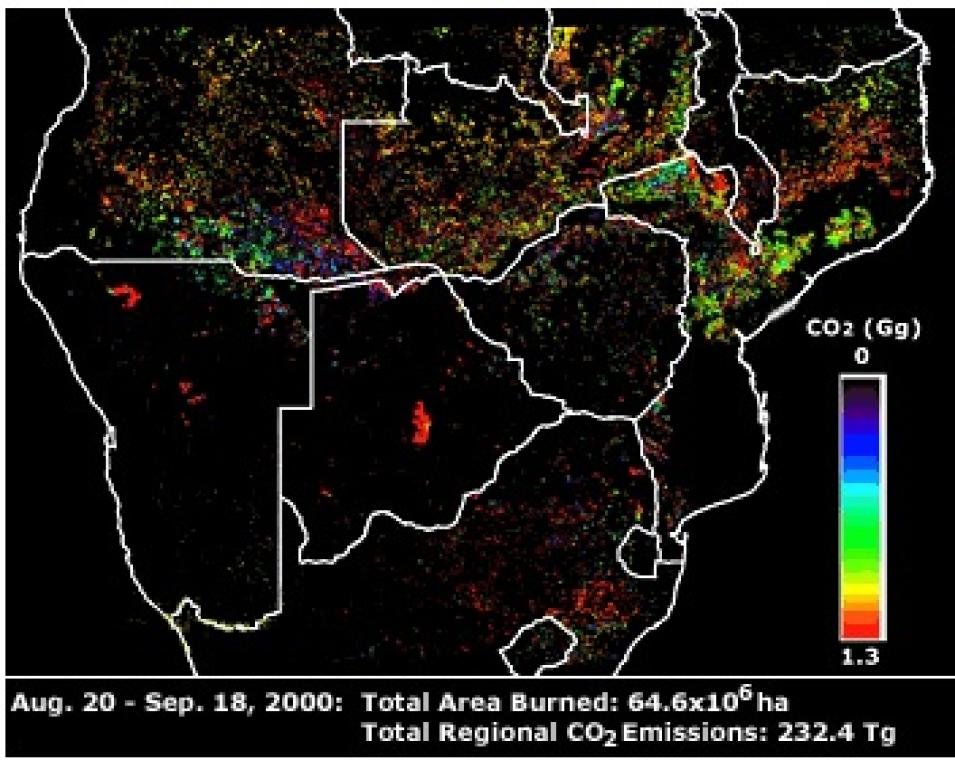

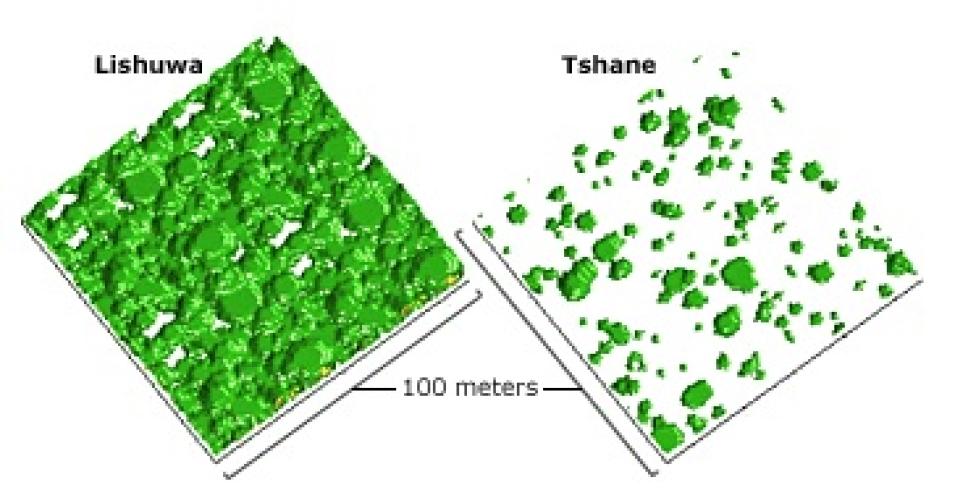

Shugart developed an interest in large-scale ecosystems as a graduate student. As a researcher in the Southern African Regional Science Initiative (SAFARI 2000), he studies the big picture by looking at interactions between the Earth, the atmosphere, and people. Shugart suspects that Africa supports two kinds of savanna. One form produces palatable vegetation that the wildlife eats and recycles locally, so the ecosystem’s nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus) remain in the system. The other form of savanna produces less palatable vegetation; rather than being consumed by animals, this vegetation accumulates, providing fuel for fires that transport nutrients somewhere else.

“If the low-nutrient ecosystems lose their nutrients, and the high-nutrient systems keep theirs, are landscape processes robbing the poor to give to the rich?” Shugart asked. If so, this reinforces a serious problem. Once an ecosystem that’s easily grazed becomes an ecosystem that’s easily burned, it rarely reverts to its previous grazable state. Exactly how ecosystems make this transition is not fully understood, but Shugart cites two lines of evidence that fire-adapted ecosystems exist in places that could support more benign vegetation: (1) previously forested regions have become fire-prone savanna, and (2) high- and low-nutrient communities exist on similar soils and under similar climatic conditions.

Sobering examples of unwanted ecosystem change can be found outside Africa. Introduced plant species have substantially changed ecosystems in North America. “Cheatgrass burns like crazy, and its seeds can withstand fire. It isn’t good for anything else, so it’s been kind of a scourge in the western United States,” said Shugart.

Livestock grazing has also produced problems. “When people first encountered the Chihuahuan Desert in New Mexico, it probably had small shrubs and aridity-tolerant grasses. Once cattle grazed it, everything turned to creosote bush, which sends roots out 50 feet from the plant and sucks up all the nutrients. So now the system is either high-nutrient with a bush growing on it or low-nutrient desert. There are no nutrients between the bushes, so the grasses can’t come back — even if you stop the livestock grazing.”

A variety of natural grazers can keep an ecosystem in balance, but livestock grazing has had far-reaching effects in Africa’s dry regions. “Africa has a beautiful assemblage of antelope, giraffes, and other big animals that eat different kinds of plants,” Shugart said. “But cattle are preferential grass eaters, so once they start grazing, the vegetation can turn thorny and shrubby. Is that a reversible condition? We’d like to know.”