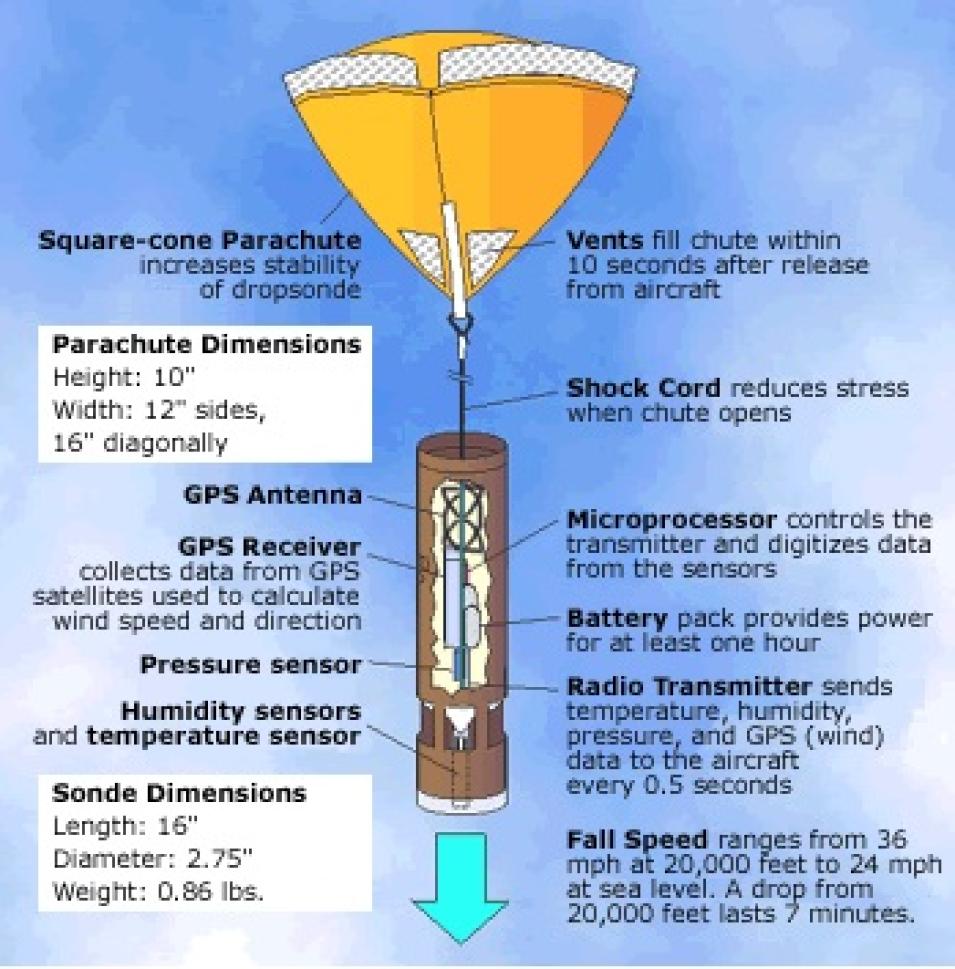

Key to the mission was a cylindrical instrument called a dropsonde, which measures roughly 3 inches in diameter and 20 inches long (7.6 centimeters in diameter and 51 centimeters long). “This technology has been around for awhile, and it involves launching robot sensors, or dropsondes, from aircraft. These sensors fall to the Earth via parachutes, taking measurements of temperature, pressure, winds, and humidity every half second,” said Halverson. During their descent, the dropsondes transmit the data to the aircraft where they are recorded for later analysis.

Although dropsondes were deployed during previous CAMEX missions, CAMEX-4 introduced a new dimension to the experiment: for the first time, dropsondes were launched from the ER-2 aircraft at an altitude of 65,000 feet (20,000 meters).

During the flight mission over Erin, Halverson was on a NOAA DC-8, situated 30,000 feet (9,100 meters) below the ER-2, telling its pilot where to release the dropsondes. “We had three different layers of aircraft flying through this storm and dropping these little instrument packages from different altitudes, and we managed to get eight of them placed very nicely,” Halverson said.

“These storms can change their structure in a matter of minutes. We’re up there in the thick of things where we can see how the storm structure is unfolding and how it’s changing as we fly through it. You can’t make those observations sitting on the ground relying on a weather satellite.”

Another boon for CAMEX-4 was that, for the first time, the entire dropsonde process was automated. “Basically, the pilot pushed a button, and when the light turned green, the dropsondes were released. In prior years, you had to have an operator sitting in front of the onboard computer telling it to pick up the dropsondes, put them in the launch tube, and open up the tube to release them,” said Halverson.