Summertime in northern Alabama means sunny family picnics and lazy afternoons by the pool. But clear skies often rapidly fill with storm clouds that produce tornadoes, hail, and lightning. While the sudden eruption of severe weather may thrill a storm chaser, it can make a forecaster cringe. Weather conditions can worsen rapidly, sometimes giving forecasters little time to assess a situation and even less time to issue a warning. Forecasters must monitor a variety of constantly changing factors affecting storm formation, but researchers have discovered that observing one of the components of severe weather, lightning, can reveal clues about an impending storm's severity.

Mapping the frequency of lightning

Richard Blakeslee has studied the relationship between lightning and storm development for more than twenty-five years. As a senior research scientist at the Global Hydrology and Climate Center (GHCC) in Huntsville, Alabama, Blakeslee has relied on a variety of methods to research lightning, and has helped develop satellite sensors to monitor lightning on a global scale. But to better understand how lightning can help make storm forecasting more accurate, he also conducts research in his own neighborhood, incorporating data from the North Alabama Lightning Mapping Array (LMA), a set of sensors that began operating in 2001.

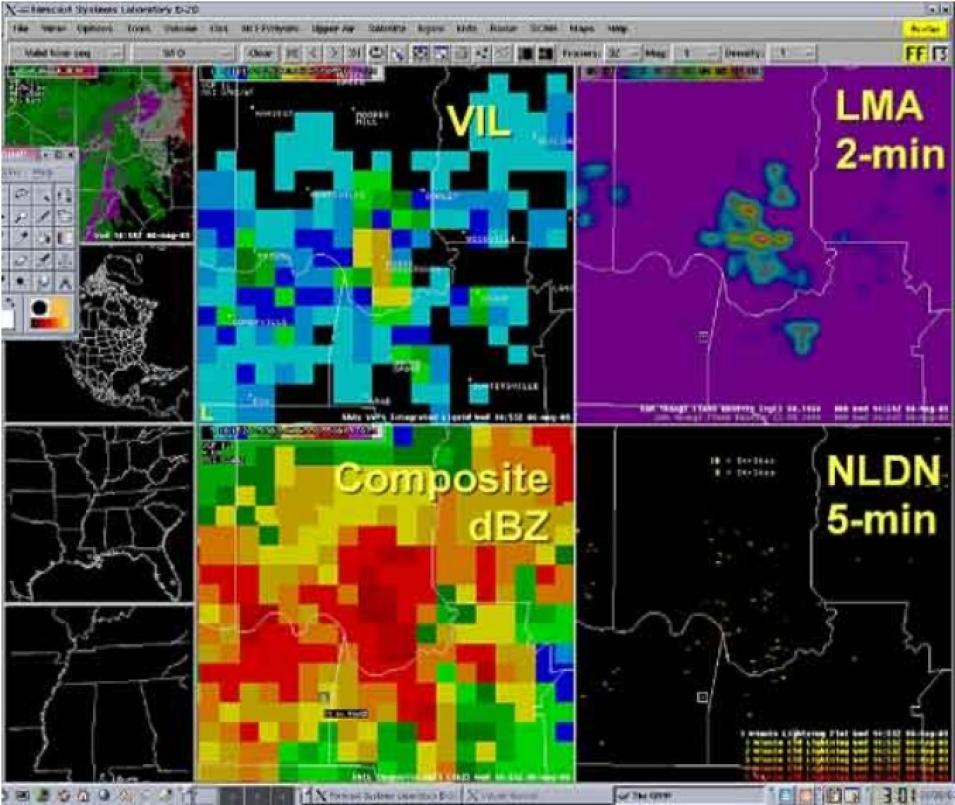

"The Lightning Mapping Array maps out lightning discharges within the clouds, providing a three-dimensional map of the lightning as it develops," Blakeslee said. The network consists of eleven receivers that capture detailed lightning observations. The LMA was initially deployed to validate the Lightning Imaging Sensor aboard the Tropical Rainforest Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite, but LMA data are also proving useful to regional forecasters on the ground. Every two minutes, data from this network are forwarded to the National Weather Service office in Huntsville responsible for forecasting in eleven northern Alabama counties and three southern Tennessee counties. The data are also provided to nearby forecast offices in Nashville, Tennessee; Birmingham, Alabama; and Jackson, Mississippi.

Using the new LMA data, Blakeslee and his colleagues studied two thunderstorms that occurred over northern Alabama in 2002, and discovered that lightning activity increased dramatically just before the storms intensified and became severe. The researchers also incorporated cloud-to-ground lightning data from the National Lightning Detection Network (NLDN). NLDN data are acquired by NASA's Global Hydrometeorology Resource Center (GHRC) from Vaisala, Incorporated, and made available to approved NASA Earth Observing System (EOS) and TRMM investigators. This combination of data allowed the team to observe the total lightning flash rate, including cloud-to-ground, intracloud, and cloud-to-cloud lightning.

By looking at the flash rate maps, the researchers discovered a pattern: an increase in total lightning activity followed by a dramatic decline often indicated the development of strong storms. This pattern of lightning activity often even preceded the occurrence of cloud-to-ground lightning strikes by several minutes--information forecasters could use to issue earlier warnings to communities and airports in a storm's path.