Serious air waves

Neil Hindley, Wright’s colleague, said, “If we could see them, we’d see the atmosphere as a large undulating mass of all kinds of waves going in all sorts of different directions, mostly from the bottom up.” Like the surface of the ocean, the atmosphere is never still, driving weather and climate.

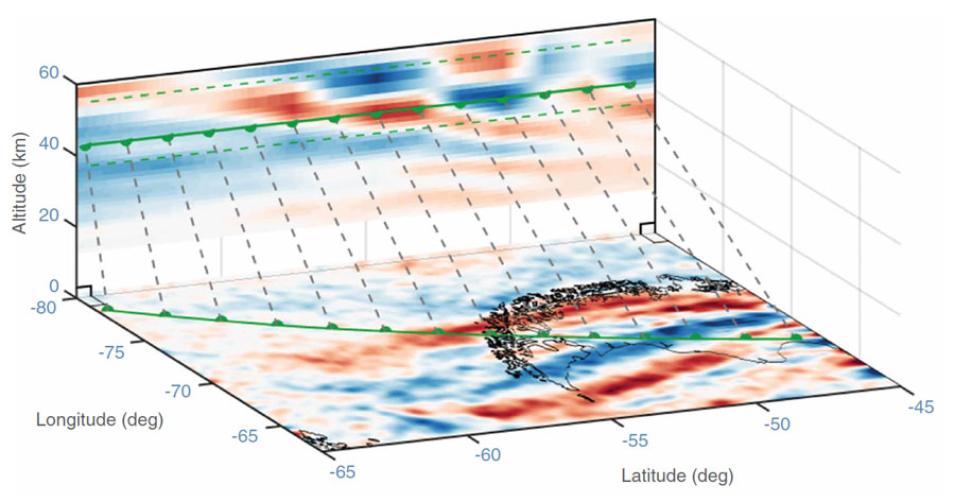

But unlike the ocean, the atmosphere has no lid, so gravity waves tend to propagate up and up. When they finally break, as ocean waves breaking on a shore, these waves of air crash and release their energy into the upper atmosphere. That can force winds to blow in different directions and amp up circulation in the atmosphere.

Hindley went on to describe the reasoning behind their name. Not to be confused with gravitational waves, which are phenomena that occur in space, gravity waves are of this world. “If I imagine myself as a pebble in a stream, the water has to flow up and over me and then down the other side,” he said. “When the water goes over the other side, it falls back down under gravity.” On the surface, water moves up and down, oscillating under gravity and creating a lasting rippling effect. This happens in the atmosphere, too, but instead of water flowing over a pebble, air flows over mountains.

Most notably, strong westerly winds flow over the mountains of the southern Andes and the Antarctic Peninsula, and are ideal conditions for generating gravity waves. Violent thunderstorms over the Southern Ocean or fluctuations in the jet stream can also create them. Wright said, “There’s a massive peak of gravity waves over the Andes that is often ten times bigger than the rest of the world.”

Nick Mitchell, also at the University of Bath, said, “Say you have a thunderstorm over the horizon. Ocean waves will flow away from the thunderstorm and break on the beach thousands and thousands of miles away from where the storm was. These do the same thing. They take energy and momentum from the lower atmosphere to the edge of space and, in so doing, influence the circulation of the atmosphere.”