How can Egyptians get rid of the black cloud? The first problem was, as Heba Marey, a scientist at Alexandria University in Egypt, said, “Researchers didn’t have a firm cause for the black cloud formation.” In 2009, as a doctoral student studying remote sensing, Marey realized that satellite data might lead to a clear answer that would be key to reducing the pollution at its source.

Worst pollution on the planet

In 2007 the World Bank ranked Cairo’s air worst in the world for pollution by particulates, the tiny fragments of soot or dust that are most damaging to human lungs. High emissions contribute to the problem, but Cairo’s topography and climate make the pollution even worse. The city lies in a valley surrounded by hills, which hold the poisoned air like water in a bowl. In the fall, frequent temperature inversions settle over Cairo—a weather phenomenon that occurs when a warmer, lighter air mass moves over a colder, denser air mass, trapping a layer of air close to the ground. The inversions still the winds, creating a stagnant soup of unmoving air. Meanwhile, an extremely dry climate means that cleansing rainstorms rarely appear.

But the black cloud is different from the pollution that plagues the city every day. It appears only once a year, in September or October. And it is much more intense than the regular pollution, darkening the sky into a foreboding smog. The black cloud brings pollution levels up to ten times the limits set by the World Health Organization, and can persist for days or weeks at a time. It sends people to the hospital with exacerbated lung infections and asthma attacks at unusually high rates, and contributes to cancer and other long-term health problems.

Before Marey started her research, the source of the pollution cloud was a mystery. People in the city blamed farmers’ fires, while many farmers, who live a hundred miles outside Cairo, argued that their smoke could not feasibly travel all the way to Cairo, and that the cause must instead be the cars and factories in the city itself. In 2004, authorities banned rice husk burning and introduced other pollution-reducing measures, but the annual cloud continued.

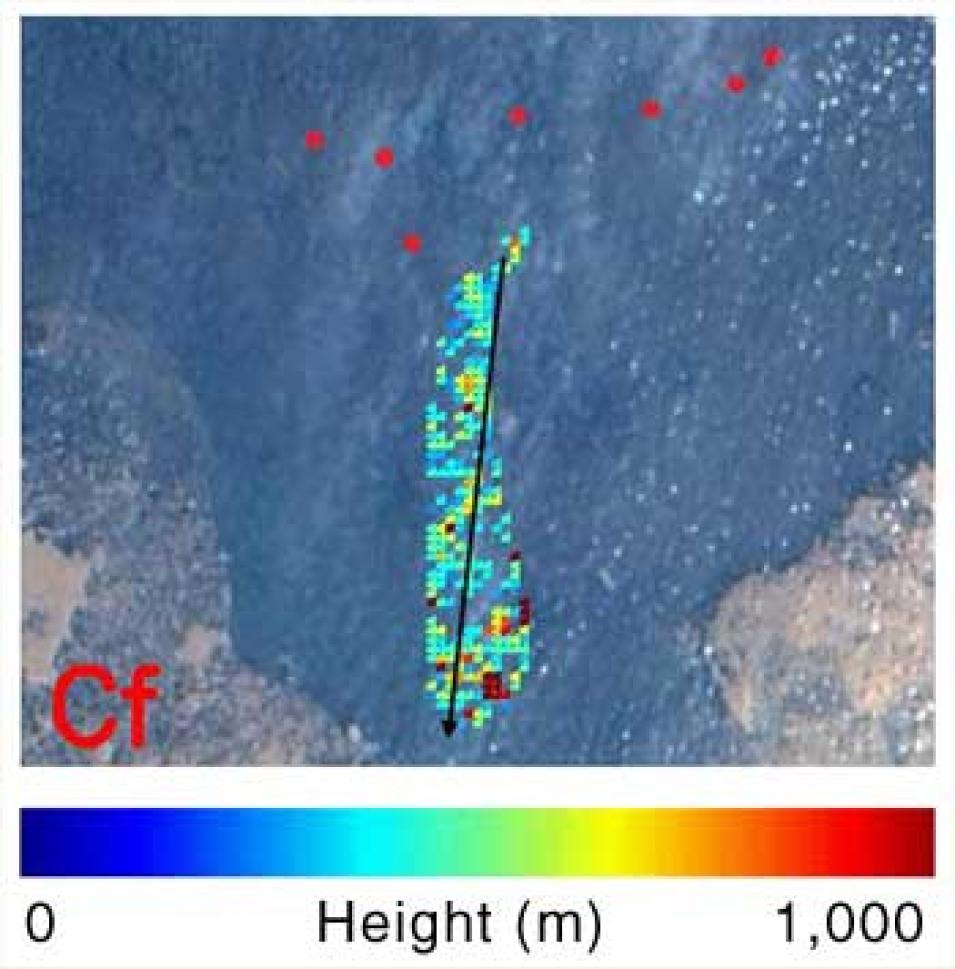

Marey wanted to look at the problem from a different perspective. Even though people had guesses about the reasons for the black clouds, the ground data available in Egypt only gave people the same information that they could already see with their own eyes: air pollution got much worse during the black cloud events.

Marey had received a research fellowship to study abroad as part of her PhD work, and decided to use it to learn more about the black cloud. She contacted John Gille at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Colorado and proposed that they work together. “NCAR is the best place in the world for atmospheric remote sensing science,” Marey said. “It was a wonderful opportunity to work there.”

When she arrived in Colorado, Gille helped Marey learn more about remote sensing and explore the available data. Then she moved on to put the pieces together for her study. Gille said, “She was very enterprising. She talked to a lot of people, asked a lot of questions, and found the data sets she needed to answer her questions.”