On March 11, 2011, a powerful earthquake shook Japan. Pressure had built along a deep ocean trench off the northeast coast, and then the fault ruptured. The quake began below the seafloor, 43 miles east of the Tohoku Region, jolting part of the seafloor upwards by 30 feet. The force of the temblor thrust Honshu—Japan’s biggest island—about 10 feet to the east.

Seismographs registered the quake’s magnitude at 9.1, the most powerful recorded in the country. In less than a minute after the quake began, early warning systems fed quake data into computer simulations. Computer models processed tide gauge and deep ocean gauge observations throughout the Pacific Ocean. These systems churned out forecasts of when destructive tidal waves, or tsunamis, might arrive at coastlines in Asia and the Americas, and how big they might be.

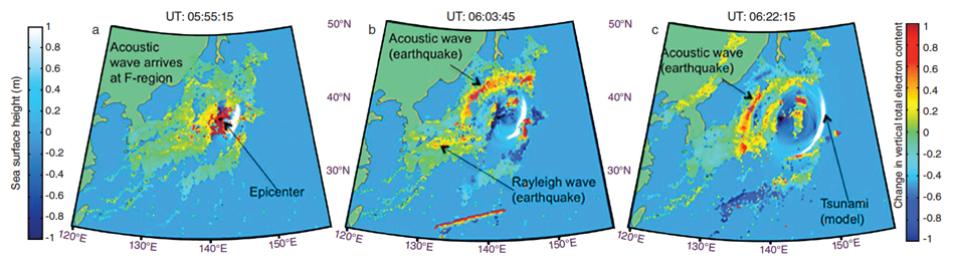

High above Japan, something else detected signals from the quake. Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites sent their usual radio signals to Earth. As the pulses beamed down to the country’s 1,200 ground-based GPS receivers, they intercepted and recorded atmospheric disturbances caused by the quake. When they arrived at the ground receivers, the radio signals carried vital information about the quake that could improve tsunami early warning systems and get people out of hazard zones faster.