A terrestrial analog

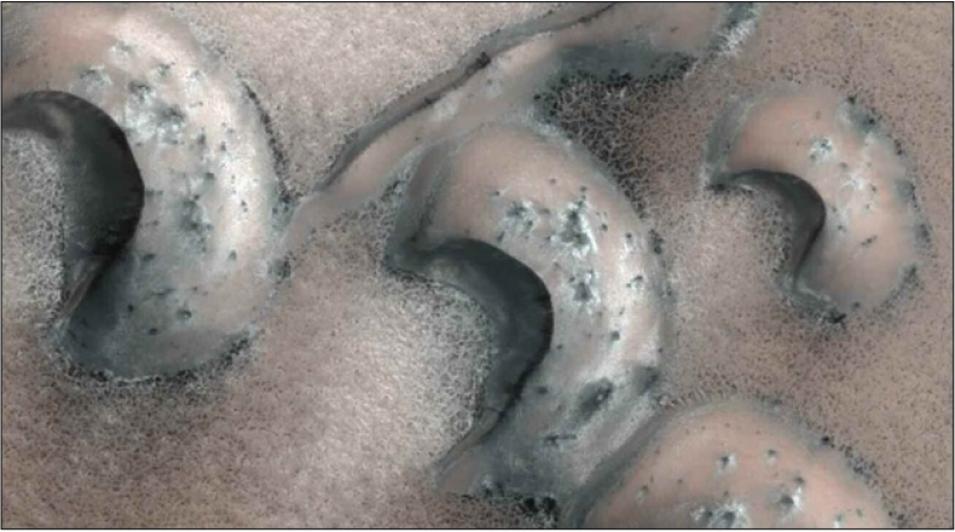

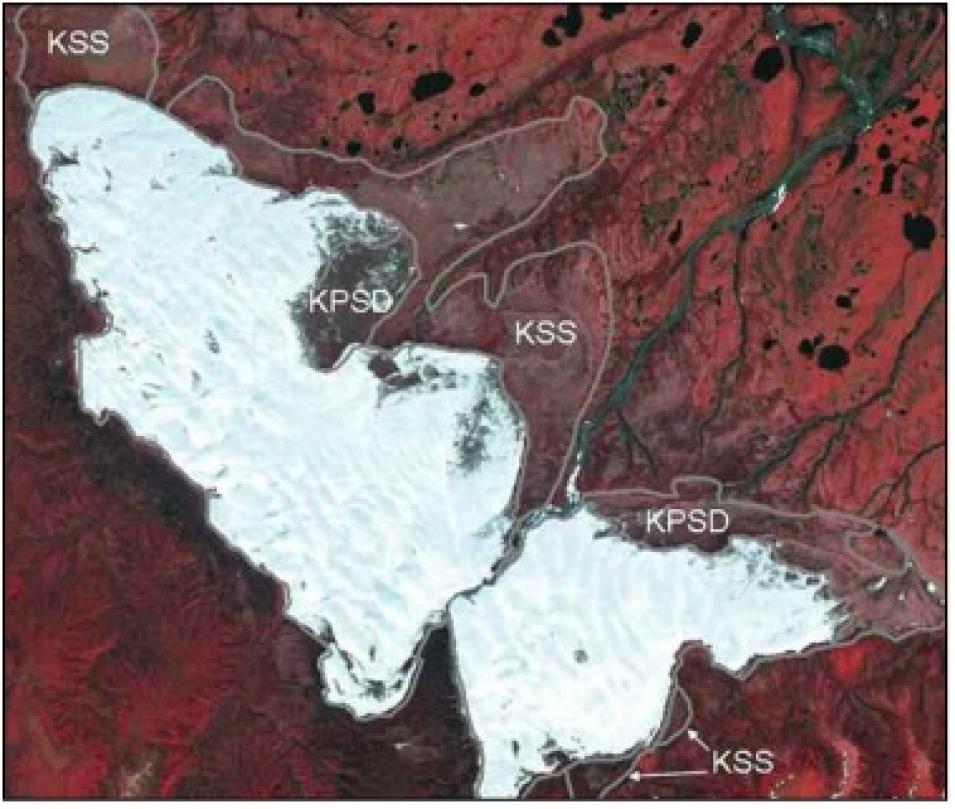

“This dune field is one of the few places on Earth where we can go and study an example of how the dunes probably are on Mars,” Hooper said. Scientists think that dune fields on Mars are locked in place somehow by frozen gases. “Because these dunes are indurated or cemented, it slows their migration rate,” Hooper said. Hydrogeologist Cynthia Dinwiddie, Hooper’s colleague at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), made the connection between Martian dunes and the Great Kobuk dunes. Dinwiddie said, “Dune fields in the polar regions of Mars are covered with carbon dioxide and water frost for three quarters of the Martian year. It got me thinking of Kobuk Valley in Alaska, where the dune system is covered with snow for three quarters of the year.”

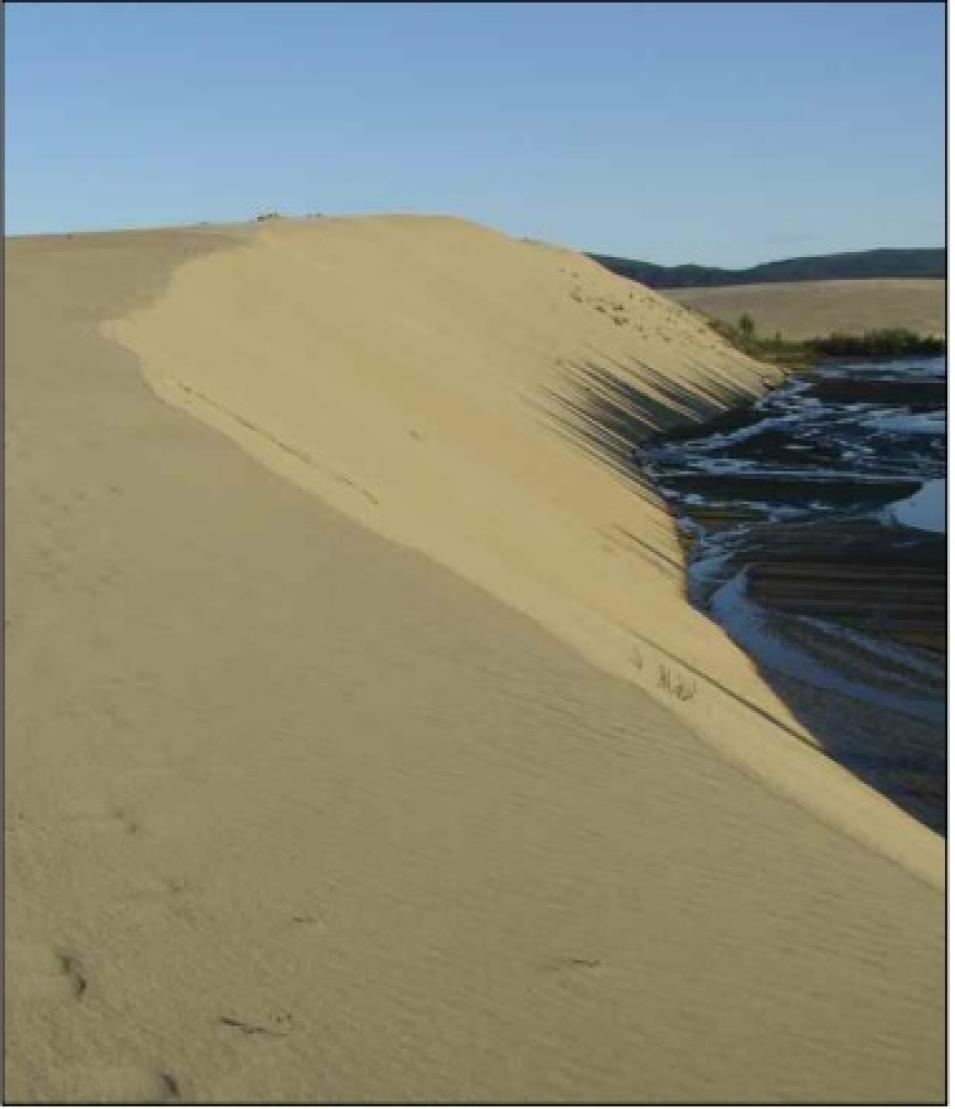

The Great Kobuk Sand Dunes is a butterfly-shaped dune system in northwestern Alaska, about sixty-five kilometers (forty miles) north of the Arctic Circle. Like most high-latitude, cold climate sand dunes, the Great Kobuk dunes move very slowly. Scientists believe that the dunes are slowed by the accumulation of snow and sand, and possibly by permafrost deep under the dune field. Although slow moving, most of the Great Kobuk dunes are classified as active, meaning the dunes still move, evolve, and are shaped by processes like wind and rain.

Reading the landscape

But what could an Alaskan dune field possibly reveal about dunes on another planet thirty-four million miles away? Hooper said, “Geomorphologists can look at the size and shape of dunes and the way they change or stay still, and be able to describe what kind of environment these dunes exist in.” A barchan dune, for example, is a crescent-shaped dune with arms or horns that point downwind. It is found in areas where wind flows from only one direction and where there is little or no vegetation. Because there is no vegetation to hold it down, a barchan dune will move across this desert, and it will not need a large supply of sand to invoke its migration. So, just looking at a barchan dune already gives a scientist wind direction, the presence or absence of vegetation, and sand supply—all important hints to the dunes’ environment.

“For Mars, the real interest in sand dunes is to find out just how alive the planet is,” Hooper said. “We know there’s wind on Mars, but we’re still trying to identify active surface processes. Being able to detect something like a dune moving, or a landslide on a steep escarpment would give us indicators that the planet is actively changing.”

To detect extremely slow sand dune movement on Mars, scientists need an efficient method to analyze thousands of large, high-resolution images. Dinwiddie said, “The resolution of the imagery for Mars is really good right now. Very recently, scientists have spotted movement of sand ripples on Mars. But researchers currently use brute force to identify movement—just looking at an image, then finding the next image of the same feature, and comparing the two.”