Even after countries receive funding, the MCC continues to evaluate their environmental performance using the NRMI, encouraging projects that foster environmental sustainability. In Nicaragua, for example, the effects of clearing land for agriculture become apparent each year during the hurricane season. During a hurricane’s heavy rain, deforested hillsides are more susceptible to landslides than are naturally forested hills. The MCC is encouraging reforestation in Nicaragua by funding tree nurseries like Rivera’s.

Raising awareness

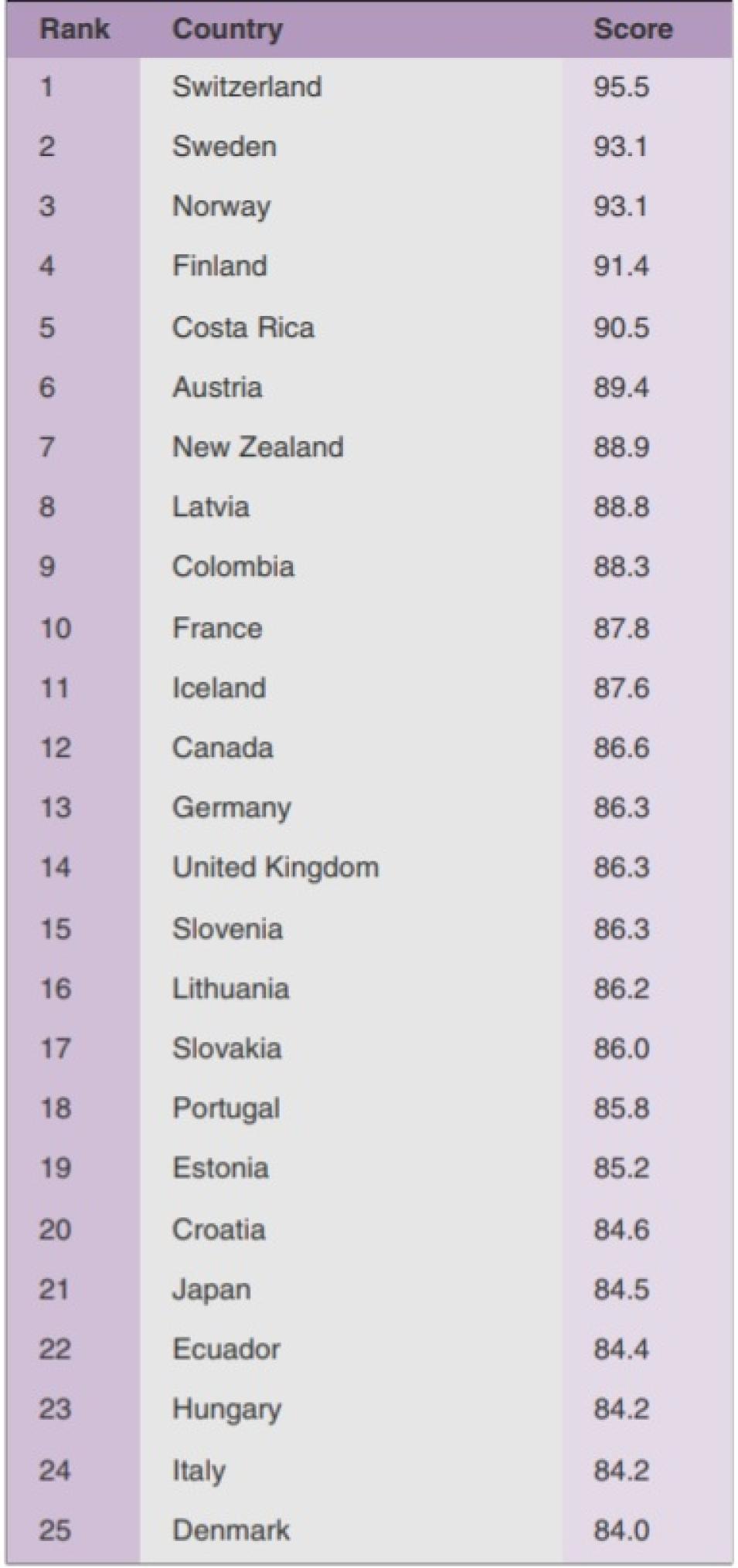

The EPI provides another incentive by harnessing the power of competition. In addition to ranking countries overall, the index ranks countries within their geographical peer group. These peer groupings permit countries to compare themselves to neighboring nations that face similar issues or geographical challenges. De Sherbinin said, “If a country sees other countries in their geographic region performing better, then it gives them less grounds to dismiss the whole effort. They can see practices in other countries that might yield positive results in their own.” For instance, in addition to promoting reforestation, Nicaragua’s government is trying to emulate Costa Rica’s successful ecotourism industry. Properly planned ecotourism helps preserve biodiversity while creating jobs and generating money to improve urban and rural infrastructure.

But even within similar geographical groupings, each nation still faces different challenges. Policy makers require more than a static snapshot, so the EPI researchers created an interactive online version of the index. Policy makers can see exactly where they have been successful, or even adjust the weight of certain indicators to reflect particular values. Levy said, “If you’re the World Wildlife Fund, you might increase the weight for ecosystem vitality. Or, if you’re the World Health Organization, you might increase the weight for environmental health indicators.” Government workers can see how their country ranking might change if they improved certain indicators, allowing them to choose which areas are most practical for them to address first.

Because few global standards exist for maintaining environmental health or ecosystem vitality, the goal of the EPI is primarily to raise consciousness and encourage sustainable environmental development. Several countries, such as South Korea and Mexico, have evaluated the EPI to see how it might help them formulate policies that would protect natural resources without hindering economic development. “One of the reasons we produced the EPI was to create a framework for how countries could improve. Luckily, the situation is getting a bit better over time,” Levy said. The EPI is giving governments data that may help improve environmental conditions in their countries, while encouraging policy makers to invest in livelihoods that foster and preserve local natural resources.

References

Esty, D. C., M. A. Levy, C. H. Kim, A. de Sherbinin, T. Srebotnjak, and V. Mara. 2008. 2008 Environmental Performance Index. New Haven: Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy.

Millennium Challenge Corporation. Women’s incomes and trees sprout up in Nicaragua. http://www.mcc.gov/documents/successstory -042308-resultsontheground-nicaragua.pdf

Sanderson, E. W., M. Jaiteh, M. A. Levy, K. H. Redford, A. V. Wannebo, and G. Woolmer. 2002. The human footprint and the last of the wild. BioScience 52: 891–904

For more information

NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC)

2008 Environmental Performance Index (EPI)

Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC)

World Data Center for Human Interactions in the Environment map gallery

| About the data |

| Data set |

2008 Environmental Performance Index (EPI) |

| Parameter |

Environmental indicators |

| DAAC |

NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC) |