A small tree with needle-like leaves, tiny pink flowers in spring, and a pretty name, tamarisk occupies a million acres in the southwestern United States. Native to Europe and Asia, these small, spreading trees were brought to the United States in the 1800s and prized for their delicate beauty, shade-filtering qualities, and ability to stabilize stream banks. There is no such love anymore for tamarisk in the United States. Now, teams of “tammywackers” spend sweaty, exhausting days trying to eradicate stands of tamarisk, using special jacks to pull these trees up by the roots, or cutting them and painting solutions on the stumps to prevent regrowth. Fighting hundreds of miles of stream bank invasion in Texas, authorities use helicopters to drop herbicides on tamarisk stands along the Pecos River. Despite these measures, the trees continue to spread throughout the southwestern United States, and beyond.

What went wrong? How did this attractive garden specimen become an invasive species, what problems does it cause, and are there better ways to control it? The United States Department of the Interior estimates that invasive plants such as tamarisk cause $20 billion each year in economic damage, and controlling their spread is not cheap either. One group of researchers is developing a new way to outwit invasives like tamarisk. Jeff Morisette, a remote sensing scientist at NASA, said, “We can use remote sensing and models to predict the spread of invasive species. By controlling spread, we can save a lot of time and money.”

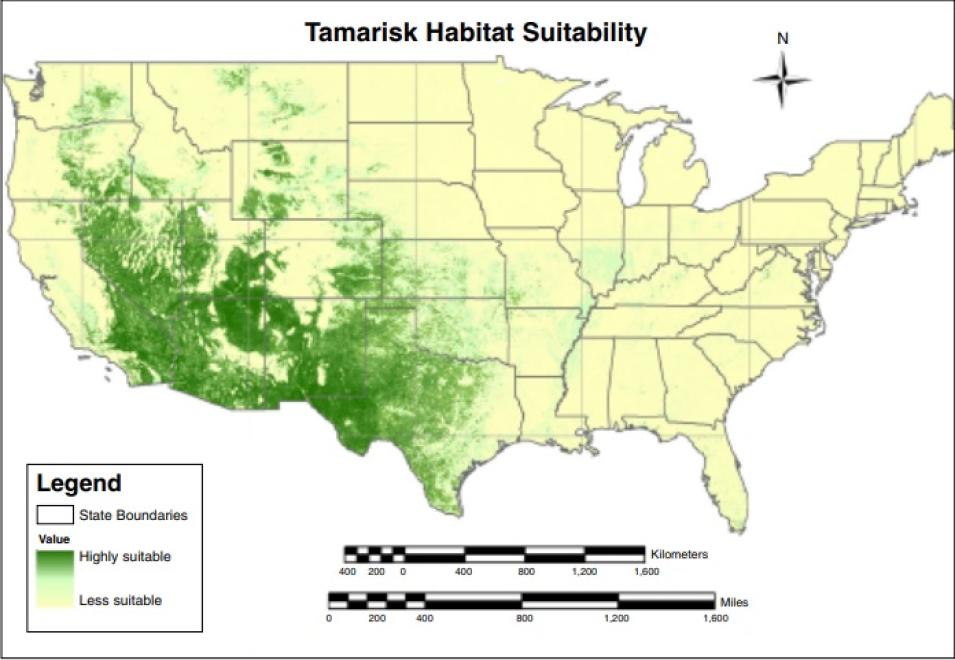

Morisette is part of an interagency team that developed a tamarisk habitat suitability map for the continental United States. Combining several environmental data layers with the analytical powers of a computer model has enabled them to produce a map that indicates where the next stand of tamarisk might crop up.

Knowing the enemy

Tamarisk (Tamarix species) is commonly called salt cedar, so named because it concentrates salts in its leaves. Its leaf litter makes the soil saltier and thus less favorable for other plants. Tenacious and tolerant of poor soils, it spreads aggressively and crowds out native trees, such as cottonwood. “Tamarisk has a deep tap root,” Morisette said. “It can outcompete other plants in drought conditions, which is why it’s a problem in the Southwest.”

Pushing out native species like cottonwood, tamarisk alters bird and insect habitat and so disrupts a long-established local food web. Cottonwood trees have palatable seeds and thick limbs to support large birds like raptors and woodpeckers. But high-density stands of spindly tamarisk offer little structural or microclimatic diversity, and do not harbor the seeds and insects that many birds eat. So the insects and birds that used the cottonwood and other native plants for habitat also decline.